Alvino Rey’s Musical Legacy

As the father of the electric guitar and grandfather of two members of Arcade Fire, Rey was a major influence on rock for decades

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Rey-studio-shot-of-Alvino-Rey-631.jpg)

At the sold-out arenas where the indie rockers of Arcade Fire perform, the specter of Alvino Rey lurks.

Handwritten postcards flash across a movie-size projection screen while band members and brothers Win and Will Butler sing from their first album, Funeral. The notes were written by Alvino Rey, the Butlers’ grandfather, who exchanged them with fellow ham radio operators. Nearby, Music Man amps project the band’s sound, amps developed in part by guitar innovator Leo Fender, who often sent his good friend Rey amps and guitars to test. And audible to everyone who’s ever listened to Arcade Fire—or the Clash, or Elvis, or any musician who’s ever played an electric instrument – are the wiring and electric pickups. Rey created those too.

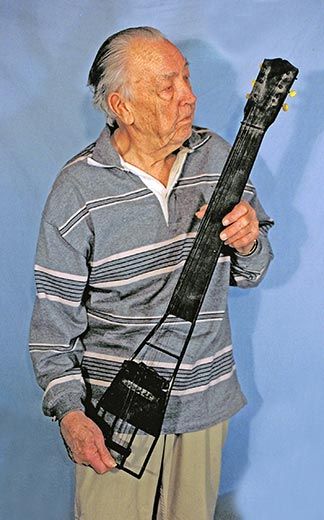

He may not be a household name today, but at the height of the swing band era Rey’s genre-busting fretwork in electric music’s nascent years helped set the stage for modern rock. According to family members, he sometimes considered himself more of a frustrated electrical engineer than a musician – and combining those two passions helped him usher in a new music era.

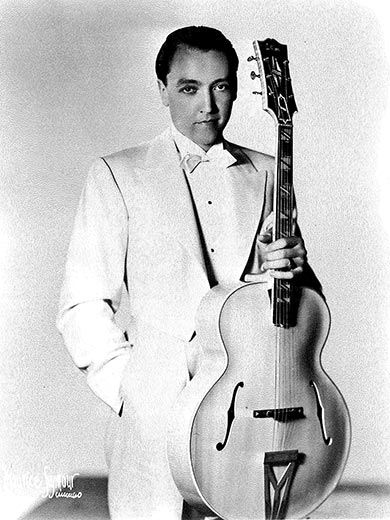

“For millions of radio listeners, the first time they heard the sound of an electric guitar, it was played by Alvino,” said Walter Carter, a former Gibson guitar company historian. Rey, born Alvin McBurney in 1908 in Oakland, California, exhibited his dual passions early. “Dad was the first one on his block to have a radio, and he built it himself,” said his daughter, Liza Rey Butler.

By 1927, his family lived in Cleveland and he played banjo with Ev Jones’ Orchestra. By the early 1930s, Rey had joined Horace Heidt’s Musical Knights in San Francisco, performing on nationally broadcast radio and touring the country.

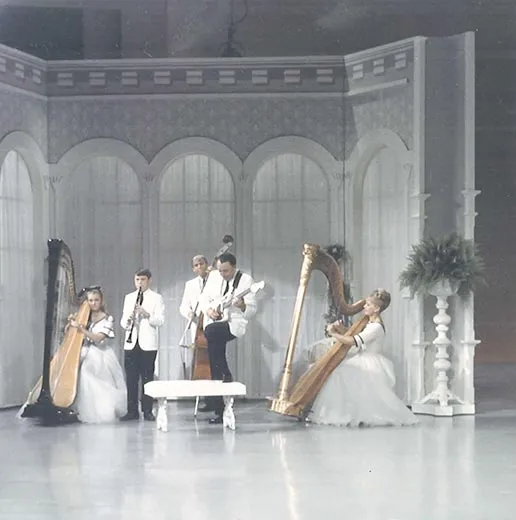

Meanwhile, in 1937, Rey married Luise King, one of the harmonizing King Sisters, and the couple soon formed their own orchestra. They were the first to record a chart-topping version of “Deep in the Heart of Texas.” (The grandson parallels continue – Win Butler also married a singer, Régine Chassagne, a member of Arcade Fire who composes and performs with her husband.)

Toward the end of World War II, Rey enlisted in the Navy. After the war, he tried to re-form his band, but it never hit the same heights.

In 1964, an anniversary television show with the King Family lead to a regular variety show that also featured the younger generation, including his three children. Rey performed at Disneyland for decades, and the King Family played at Ronald Reagan’s second presidential inauguration in 1985 (Arcade Fire played at President Barack Obama’s inaugural celebration 24 years later).

But he never left behind the electronics.

“You should have heard him on stage with a regular guitar—holy god,” said Lynn Wheelwright, Rey’s guitar technician and friend. “Alvino opened every show with a guitar solo, he closed every show with a guitar solo, and he had a guitar solo in every song. He found a way to use the instrument in such a way that people would buy them and use them.” At first, Rey plugged his guitar directly into the radio station’s transponder, Wheelwright said. But if the sound he wanted wasn’t readily available through his instruments, he tweaked the wires himself.

Rey was, by all accounts, the most famous musician to join guitar and electronics at the time, and the first to play for a national audience, which he did as a part of the Horace Heidt’s radio program.

He was best known for his work on the lap steel guitar. The lap steel was mostly the purview of Hawaiian and country and western styles – until Rey started playing swing band chords. According to Carter, because the lap steel has to be played flat, it doesn’t project sound as far as a guitar held in the standard position.

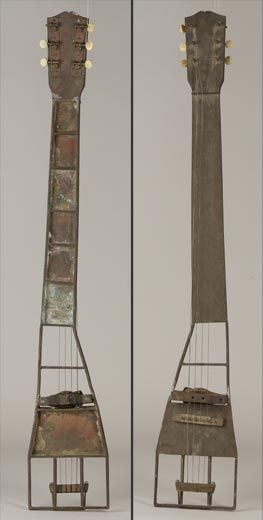

“There’s Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock guitar, Eric Clapton’s Brownie, which he played on “Layla,” and there’s Alvino,” said Jacob McMurray, a senior curator at Seattle’s Experience Museum Project/Science Fiction Museum, where Rey’s prototype for the electric lap steel guitar is on permanent display. Rey helped develop that prototype as a consultant for the Gibson company, but how he played was also an innovation.

“Companies started making larger and louder Spanish-neck guitars, which worked fine for the rhythmic parts in a big band. But Hawaiian players, who typically played lead parts, could not be heard. So they embraced the new electrics,” Carter said.

In 1935, Gibson hired Rey, who worked with the company’s engineers to create the prototype that hangs in Seattle. Rey’s invention was used to build Gibson’s ES-150 guitar, considered the first modern electric guitar.

“Charlie Christian’s pioneering jazz guitar work is always singled out [for popularizing the ES-150], and deservedly so, as a key factor in Gibson’s success as a maker of electric guitars, but Alvino Rey was equally important, and sadly, he is seldom mentioned,” Carter said.

By the 1940s, another electric inventor had entered the music scene – Leo Fender; he and Rey became close friends.

“We had so many [Fenders] in our house you couldn’t walk,” Liza Butler said. “In my kitchen, I have a chopping block Leo Fender made out of all the old Fender guitar necks from the factory.”

Rey’s influence can be seen elsewhere. By connecting a microphone to his lap steel, Rey created the first talk box, manipulating a speaker’s voice with his strings. Decades later, Peter Frampton would become synonymous with the talk box, with his mega-selling album Frampton Comes Alive. But Rey was the first.

“I think [Mom] wished that he didn’t hang wires all over the house –no woman would—but she’d put up with it,” Liza Butler said. Both she and Wheelwright recalled a 1950s Cadillac Rey drove with the backseat replaced by amps. The Reys always had a recording studio at home. She remembers a visit when her 12- and 14-year-old sons stayed up past 2 a.m. recording in the basement – with grandpa at the controls.

“He was a very, very funny, very kind, very unselfish person,” Butler said. “He was a pilot, he loved to cook, he loved the ham radio. I hate the word humble, but it was not about him.”

But sometimes he rued what he helped create.

“He would say little smarty remarks about [rock] artists, but he would still respect them, and anyone who was successful,” said his son, Jon Rey, who lives in his parents’ old house. “I’m sure my dad would just be totally thrilled at what Win [Butler] is doing. I don’t know if he would like his music too much.”

At the time of his death, at age 95 in 2004, Alvino Rey was working on a new recording, his daughter said.

“He never felt he could retire,” she said. “It was this passion for doing more. His legacy was – tell our story, and make sure people hear these songs, and don’t let them die.”

Before the year ended, his grandsons’ band released its first album, Funeral, to critical acclaim.

“His funeral was really kind of amazing,” Will Butler said, describing how his great-aunts and other relatives performed. “It was just this really wonderful celebration that really circled around music and family. I don’t know if I’d been to any funerals at that point, and it was a powerful experience.”

“Alvino lived with his wife and ran a band, and now Win lives with his wife and runs a band,” Will Butler said. “They were musicians, and had a family, and had a larger musical family around them—it was a common cause. That’s very apropos to us.”

Will Butler, too, doubts his grandfather would have liked Arcade Fire’s music, but he says that laughing. His grandfather, Butler says, was a far better musician.