An Exploration of Latino Art at the Smithsonian

Smithsonian Secretary G. Wayne Clough previews a new exhibit at the American Art Museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/USA-made-Smithsonian-hand-631.jpg)

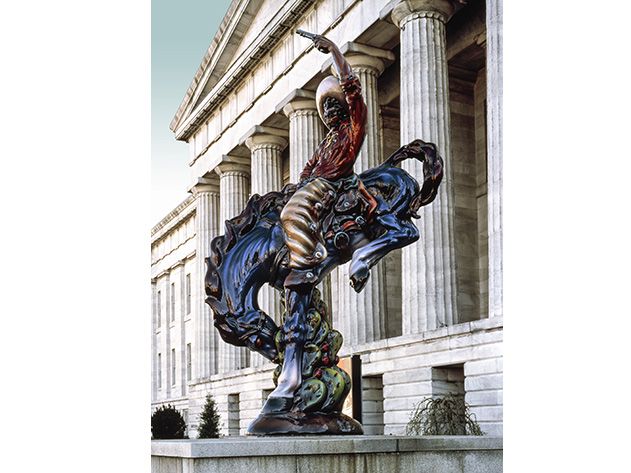

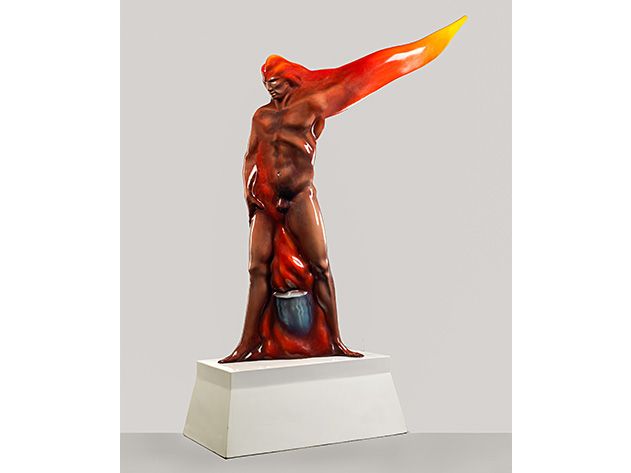

Vaquero, a larger-than-life sculpture by Luis Jiménez, which stands just outside an entrance to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, is impossible to miss. It depicts a colorful Mexican cowboy firing his pistol while riding a bucking blue horse that seems about to leap onto the museum’s steps. Added to our collection in 1990, it’s a strong nod to the long-standing and growing impact of Latino American artists on our culture—a contribution that has often been overlooked. An exhibition opening this month at the museum, “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art,” will highlight a chapter of art history that remains a secret to far too many Americans.

Since joining the Smithsonian in 2010, E. Carmen Ramos, the curator of Latino art at the American Art Museum, has had an ambitious mandate: to strengthen our holdings of Latino art and present that collection in a fresh way. “Our America,” which she curated, will display the results of that quest so far. It will include 92 works (by 72 artists), fully 63 of which have been acquired since 2011.

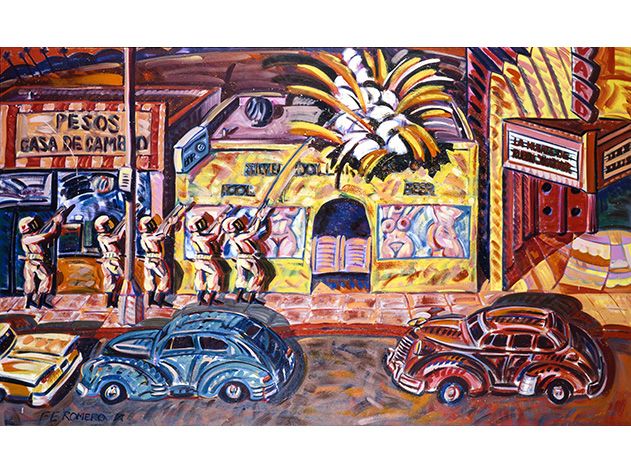

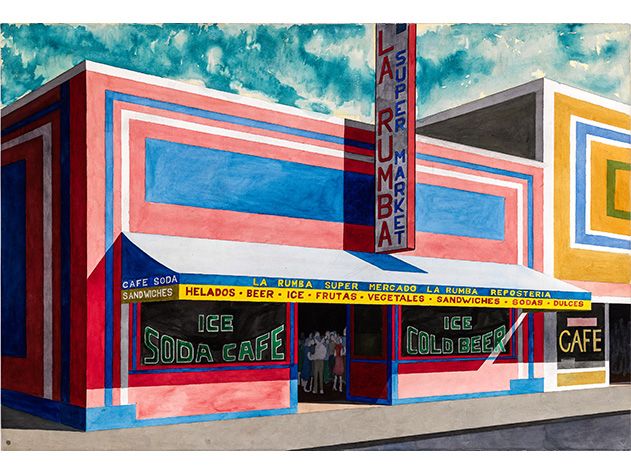

The exhibition “will be presenting these artists as protagonists in American art, which is not how we normally see them,” Ramos says. It’s far more typical, she says, to view the works as engaged in a conversation exclusively with other Latino works. In contrast, this exhibition will tell the largely untold story of how Latino artists contributed to all of the major movements in modern American art, while putting their own cultural stamp on those styles.

“Our America” focuses on the period since roughly the middle of the 20th century, when Latino artists consciously embraced, or wrestled with, their identity.

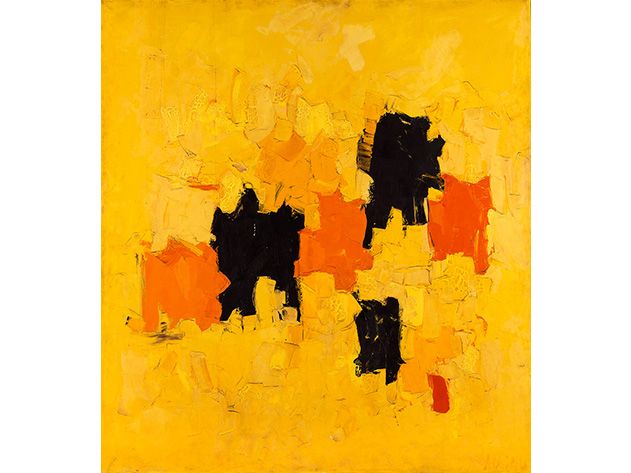

Carmen Herrera is one artist who has remained a secret for too long. Herrera emigrated from Cuba to New York in 1939, sojourned in Paris and was part of New York’s abstract-art scene, yet she’s only recently been rescued from obscurity. Visitors can compare her Blanco y Verde (“White and Green”) with the far more famous Blue on White, by Ellsworth Kelly, her peer, also on view at American Art.

The exhibition will make clear that there is no single “Latino” perspective. Some artists felt driven to engage with social issues, such as the treatment of immigrant farmworkers. Others, like Jesse Treviño, a photorealist painter, memorialized strong family and community bonds. Three eight-foot-high paintings by Freddy Rodríguez will be on view, their zigzag shapes in vibrant colors reflecting the influence of Dominican merengue music.

Those paintings can all but get your toes tapping, and his tall, slender canvases even call to mind dancers. When his Danza Africana, Danza de Carnaval and Amor Africano are hung together, as they will be in the exhibit, “it looks like a party,” Ramos says.

A party that will hit the road. After this exhibition closes in early March, it will begin a national tour.