An Eye for Genius: The Collections of Gertrude and Leo Stein

Would you have bought a Picasso painting in 1905, before the artist was known? These siblings did

With its acid colors and slapdash brush strokes, the painting still jolts the eye. The face, blotched in mauve and yellow, is highlighted with thick lines of lime green; the background is a rough patchwork of pastel tints. And the hat! With its high blue brim and round protuberances of pink, lavender and green, the hat is a phosphorescent landscape by itself, improbably perched on the head of a haughty woman whose downturned mouth and bored eyes seem to be expressing disdain at your astonishment.

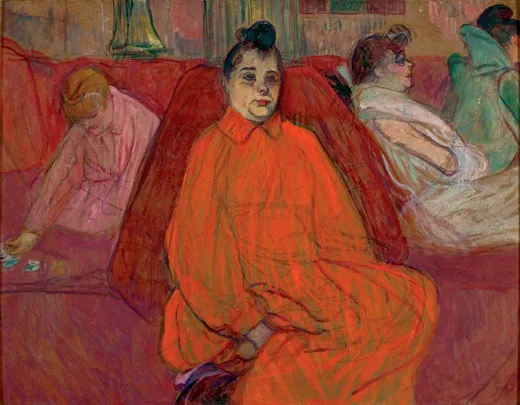

If the picture startles even after a century has passed, imagine the reaction when Henri Matisse’s Woman with a Hat was first exhibited in 1905. One outraged critic ridiculed the room at the Grand Palais in Paris, where it reigned alongside the violently hued canvases of like-minded painters, as the lair of fauves, or wild animals. The insult, eventually losing its sting, stuck to the group, which also included André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck. The Fauves were the most controversial artists in Paris, and of all their paintings, Woman with a Hat was the most notorious.

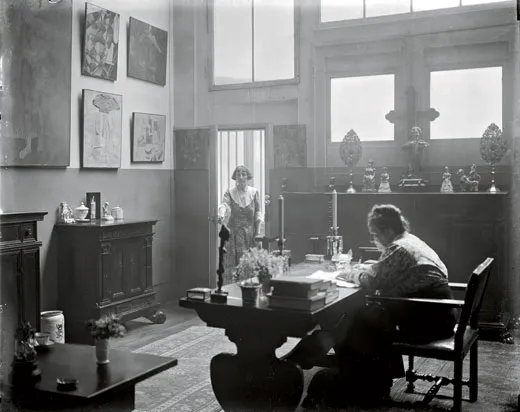

So when the picture was later hung in the Parisian apartment of Leo and Gertrude Stein, a brother and sister from California, it made their home a destination. “The artists wanted to keep seeing that picture, and the Steins opened it up to anyone who wanted to see it,” says Janet Bishop, curator of painting and sculpture at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which organized “The Steins Collect,” an exhibition of many pieces the Steins held. The exhibition goes on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City from February 28 to June 3. (An unrelated exhibition, “Seeing Gertrude Stein: Five Stories,” about her life and work, remains at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery until January 22.)

When Leo Stein first saw Woman with a Hat, he thought it “the nastiest smear of paint” he had ever encountered. But for five weeks, he and Gertrude went to the Grand Palais repeatedly to look at it, and then succumbed, paying Matisse 500 francs, the equivalent then of about $100. The purchase helped establish them as serious collectors of avant-garde art, and it did still more for Matisse, who had yet to find generous patrons and desperately needed the money. Over the next few years, he would come to rely for financial and moral support on Gertrude and Leo, and even more on their brother Michael and his wife, Sarah. And it was at the Steins’ that Matisse first came face to face with Pablo Picasso. The two would embark on one of the most fruitful rivalries in art history.

For a few years the California Steins formed, improbably enough, the most important incubator for the Parisian avant-garde. Leo led the way. The fourth of five surviving children born to a German Jewish family that had relocated from Baltimore to Pittsburgh and eventually to the San Francisco Bay area, he was a precocious intellectual and, in childhood, the inseparable companion of his younger sister, Gertrude. When Leo enrolled at Harvard in 1892, she followed him, taking courses at the Harvard Annex, which later became Radcliffe. When he went to the World Exposition in Paris in the summer of 1900, she accompanied him. Leo, then 28, liked Europe so much that he stayed, residing first in Florence and then moving to Paris in 1903. Gertrude, two years younger, visited him in Paris that fall and did not look back.

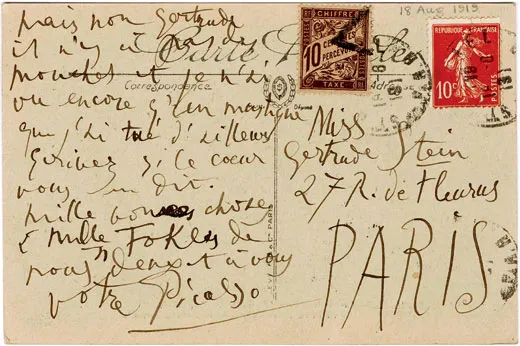

By then Leo had already abandoned his ideas of taking up law, history, philosophy and biology. In Florence he had befriended the eminent art historian Bernard Berenson and resolved to become an art historian, but he scrapped that ambition, too. As James R. Mellow observed in the 1974 book Charmed Circle: Gertrude Stein and Company, Leo led “a life of perennial self-analysis in the pursuit of self-esteem.” Dining in Paris with the cellist Pablo Casals in 1903, Leo decided he would be an artist. He returned to his hotel that night, lit a blaze in the fireplace, stripped off his clothes and sketched himself nude by the flickering light. Thanks to his uncle, the sculptor Ephraim Keyser, who had just rented a place of his own in Paris, Leo found 27 rue de Fleurus, a two-story residence with an adjoining studio, on the Left Bank near the Luxembourg Gardens. Gertrude soon joined him there.

The source of the Steins’ income was back in California, where their eldest sibling, Michael, had shrewdly managed the business he inherited upon the death of their father in 1891: San Francisco rental properties and streetcar lines. (The two middle children, Simon and Bertha, perhaps lacking the Stein genius, fail to figure much in the family chronicles.) Reports of life in Paris tantalized Michael. In January 1904, he resigned his post as division superintendent of the Market Street Railway in San Francisco so that, with Sarah and their 8-year-old son, Allan, he could join his two younger siblings on the Left Bank. Michael and Sarah took a year’s lease on an apartment a few blocks from Gertrude and Leo. But when the lease was up, they could not bring themselves to return to California. Instead, they rented another apartment close by, on the third floor of a former Protestant church on the rue Madame. They would stay in France for 30 years.

All four of the Paris-based Steins (including Sarah, a Stein by marriage) were natural collectors. Leo pioneered the path, frequenting the galleries and the conservative Paris Salon. He was dissatisfied. He felt he was more on track when he visited the first Autumn Salon in October 1903—it was a reaction to the Paris Salon’s traditionalism—returning many times with Gertrude. He later recounted that he “looked again and again at every single picture, just as a botanist might at the flora of an unknown land.” Still, he was confused by the abundance of art. Consulting Berenson for advice, he set off to investigate the paintings of Paul Cézanne at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery.

The place looked like a junk shop. Although Vollard was resistant to selling pictures to buyers he didn’t know, Leo coaxed an early Cézanne landscape out of him. When brother Michael informed Gertrude and Leo that an unexpected windfall of $1,600, or 8,000 francs, was due to them, they knew what to do. They would buy art at Vollard’s. Established first-rate artists like Daumier, Delacroix and Manet were so expensive that the budding collectors could only afford minor pictures by them. But they were able to buy six small paintings: two each by Cézanne, Renoir and Gauguin. A few months later, Leo and Gertrude returned to Vollard’s and purchased Madame Cézanne with a Fan, for 8,000 francs. In two months, they had spent some $3,200 (equivalent to about $80,000 today): Never again would they lavish so much so fast on art. Vollard would often say approvingly that the Steins were his only clients who collected paintings “not because they were rich, but despite the fact that they weren’t.”

Leo comprehended Cézanne’s importance very early, and spoke eloquently about it. “Leo Stein began to talk,” the photographer Alfred Stieglitz later recalled. “I quickly realized I had never heard more beautiful English nor anything clearer.” Corresponding with a friend late in 1905, Leo wrote that Cézanne had “succeeded in rendering mass with a vital intensity that is unparalleled in the whole history of painting.” Whatever Cézanne’s subject matter, Leo continued, “there is always this remorseless intensity, this endless unending gripping of the form, the unceasing effort to force it to reveal its absolute self-existing quality of mass....Every canvas is a battlefield and victory an unattainable ideal.”

But Cézanne was too expensive to collect, so the Steins sought out emerging artists. In 1905, Leo stumbled upon Picasso’s work, which was being exhibited at group shows, including one staged in a furniture store. He bought a large gouache (opaque watercolor) by the then obscure 24-year-old artist, The Acrobat Family, later attributed to his Rose Period. Next he purchased a Picasso oil, Girl with a Basket of Flowers, even though Gertrude found it repellent. When he told her at dinner he had bought the picture, she threw down her silverware. “Now you’ve spoiled my appetite,” she declared. Her opinion changed. Years later, she would turn down what Leo characterized as “an absurd sum” from a would-be buyer of Girl with a Basket of Flowers.

At the same time, Leo and Gertrude were warming to Matisse’s harder-to-digest compositions. When the two bought Woman with a Hat at the 1905 Autumn Salon in the Grand Palais, they became the only collectors who had acquired works by both Picasso and Matisse. Between 1905 and 1907, said Alfred Barr Jr., the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, “[Leo] was possibly the most discerning connoisseur and collector of 20th-century painting in the world.”

Picasso recognized that the Steins could be useful, and he began to cultivate them. He produced flattering gouache portraits of Leo, with an expression that was earnest and profoundly thoughtful, and of a sensitive young Allan. With his companion, Fernande Olivier, he dined at the rue de Fleurus flat. Gertrude later wrote that when she reached for a roll on the table, Picasso beat her to it, exclaiming, “This piece of bread is mine.” She burst out laughing, and Picasso, sheepishly acknowledging that the gesture betrayed his poverty, smiled back. It sealed their friendship. But Fernande said that Picasso had been so impressed by Gertrude’s massive head and body he wanted to paint her even before he knew her.

Like Cézanne’s Madame Cézanne with a Fan and Matisse’s Woman with a Hat, his Portrait of Gertrude Stein represented the subject seated in a chair and looking down at the viewer. Picasso was jousting directly with his rivals. Gertrude was delighted by the outcome, writing some years later that “for me, it is I, and it is the only reproduction of me which is always I, for me.” When people told Picasso that Gertrude didn’t resemble her portrait, he would reply, “She will.”

It was probably the fall of 1906 when Picasso and Matisse met at the Steins. Gertrude said they exchanged paintings, each choosing the other’s weakest effort. They would see each other at the Saturday evening salons initiated by Gertrude and Leo on the rue de Fleurus and the Michael Steins on the rue Madame. These organized viewings came about because Gertrude, who used the studio for her writing, resented unscheduled interruptions. In Gertrude’s flat, the pictures were tiered three or four high, above heavy wooden Renaissance-era furniture from Florence. The illumination was gaslight; electric lighting didn’t replace it until a year or so before the outbreak of World War I. Still, the curious flocked to the Steins. Picasso called them “virginal,” explaining: “They are not men, they are not women, they are Americans.” He took many of his artist friends there, including Braque and Derain, and the poet Apollinaire. By 1908, Sarah reported, the crowds were so pressing that it was impossible to hold a conversation without being overheard.

In 1907 Leo and Gertrude acquired Matisse’s Blue Nude: Memory of Biskra, which depicts a reclining woman with her left arm crooked above her head, in a garden setting of bold crosshatchings. The picture, and other Matisses the Steins picked up, hit a competitive nerve in Picasso; in his aggressive Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (an artistic breakthrough, which went unsold for some years) and the related Nude with Drapery, he mimicked the woman’s gesture in Blue Nude, and he extended the crosshatchings, which Matisse had confined to the background, to cover the figures. The masklike face of Gertrude in Picasso’s earlier portrait proved to be a transition to the faces in these pictures, which derived from bold, geometric African masks. According to Matisse, Picasso became smitten with African sculpture after Matisse, on his way to the Steins, picked up a small African head in an antiques shop and, upon arriving, showed it to Picasso, who was “astonished” by it.

Music was one of the last Matisses that Gertrude and Leo bought, in 1907. Beginning in 1906, however, Michael and Sarah collected Matisse’s work primarily. Only a world-class catastrophe—the earthquake in San Francisco on April 18, 1906—slowed them down. They returned home with three paintings and a drawing by Matisse—his first works seen in the United States. Happily, the Steins discovered little damage to their holdings and returned to Paris in mid-November to resume collecting, trading three paintings by other artists for six Matisses. Michael and Sarah were his most fervent buyers until the Moscow industrialist Sergei Shchukin saw their collection on a visit to Paris in December 1907. Within a year, he was Matisse’s chief patron.

Gertrude’s love of art informed her work as a writer. In a 1934 lecture, she remarked that a Cézanne painting “always was what it looked like the very essence of an oil painting because everything was always there, really there.” She built up her own sentences by using words in the deliberate, repetitive, blocky way in which Cézanne employed small planes of color to render mass on a two-dimensional canvas.

The 1909 publication of Three Lives, a collection of stories, marked Gertrude’s first literary success. The following year, Alice B. Toklas, who, like Gertrude, came from a middle-class Jewish family in San Francisco, moved into the rue de Fleurus apartment and became Gertrude’s lifelong companion. Leo, possibly chafing at his sister’s literary success, later wrote that Toklas’ arrival eased his imminent rupture with Gertrude, “as it enabled the thing to happen without any explosion.”

Gertrude’s artistic choices grew bolder. As Picasso staked out increasingly adventurous territory, many of his patrons grumbled and refused to follow. Leo, for one, derided Demoiselles as a “horrible mess.” But Gertrude applauded the landscapes that Picasso painted in Horta de Ebro, Spain, in the summer of 1909, which marked a crucial stage in his transition from Cézanne’s Post-Impressionism into the new territory of Cubism. Over the next few years, his Analytical Cubist still lifes, which fragmented the picture into visual shards, alienated people still more. Picasso deeply appreciated Gertrude’s purchase of some of these difficult paintings. The first work she bought without Leo was The Architect’s Table, a somber-colored, oval Analytical Cubist painting of 1912 that contains, amid the images of things one might find on such a table, a few messages: one, the boldly lettered “Ma Jolie,” or “My Pretty One,” refers covertly to Picasso’s new love, Eva Gouel, for whom he would soon leave Fernande Olivier; and another, less prominent, is Gertrude’s calling card, which she had left one day at his studio. Later that year she bought two more Cubist still lifes.

At the same time, Gertrude was losing interest in Matisse. Picasso, she said, “was the only one in painting who saw the twentieth century with his eyes and saw its reality and consequently his struggle was terrifying.” She felt a particular kinship with him because she was engaged in the same struggle in literature. They were geniuses together. A split with Leo, who loathed Gertrude’s writing, was unavoidable. It came in 1913, he wrote to a friend, because “it was of course a serious thing for her that I can’t abide her stuff and think it abominable....To this has been added my utter refusal to accept the later phases of Picasso with whose tendency Gertrude has so closely allied herself.” But Leo, too, was disenchanted with Matisse. The living painter he most admired was Renoir, whom he considered unsurpassed as a colorist.

When brother and sister parted ways, the prickly question was the division of spoils. Leo wrote to Gertrude that he would “insist with happy cheerfulness that you make as clean a sweep of the Picassos as I have of the Renoirs.” True to his word, when he departed in April 1914 for his villa on a hillside outside Florence, he left behind all his Picassos except for some cartoonlike sketches that the artist had made of him. He also relinquished almost every Matisse. He took 16 Renoirs. Indeed, before departing he sold several pictures so that he could buy Renoir’s florid Cup of Chocolate, a painting from about 1912, depicting an overripe, underdressed young woman sitting at a table languidly stirring her cocoa. Suggesting how far he had strayed from the avant-garde, he deemed the painting “the quintessence of pictorial art.” But he remained loyal to Cézanne, who had died less than a decade earlier. He insisted on keeping Cézanne’s small but beautiful painting of five apples, which held a “unique importance to me that nothing can replace.” It broke Gertrude’s heart to give it up. Picasso painted a watercolor of a single apple and gave it to her and Alice as a Christmas present.

The outbreak of hostilities between Gertrude and Leo coincided with aggression on a global scale. World War I had painful personal consequences for Sarah and Michael, who, at Matisse’s request, had lent 19 of his paintings to an exhibition at Fritz Gurlitt’s gallery in Berlin in July 1914. The paintings were impounded when war was declared a month later. Sarah referred to the loss as “the tragedy of her life.” Matisse, who naturally felt terrible about the turn of events, painted portraits of Michael and Sarah, which they treasured. (It is not clear if he sold or gave the paintings to them.) And they continued to buy Matisse paintings, although never in the volume that they could afford earlier. When Gertrude needed money to go with Alice to Spain during the war, she sold Woman with a Hat—the painting that more or less started it all—to her brother and sister-in-law for $4,000. Sarah and Michael’s friendship with Matisse endured. When they moved back to California in 1935, three years before Michael’s death, Matisse wrote to Sarah: “True friends are so rare that it is painful to see them move away.” The Matisse paintings they took with them to America would inspire a new generation of artists, notably Richard Diebenkorn and Robert Motherwell. The Matisses that Motherwell saw as a student on a visit to Sarah’s home “went through me like an arrow,” Motherwell would say, “and from that moment, I knew exactly what I wanted to do.”

With a few bumps along the way, Gertrude maintained her friendship with Picasso, and she continued to collect art until her death, at age 72, in 1946. However, the rise in Picasso’s prices after World War I led her to younger artists: among them, Juan Gris, André Masson, Francis Picabia and Sir Francis Rose. (At her death, Stein owned nearly 100 Rose paintings.) Except for Gris, whom she adored and who died young, Gertrude never claimed that her new infatuations played in the same league as her earlier discoveries. In 1932 she proclaimed that “painting now after its great period has come back to be a minor art.”

She sacrificed major works to pay living expenses. As Jewish Americans in World War II, she and Alice retreated to the relative obscurity of a French farmhouse. They took only two paintings with them: Picasso’s portrait of Gertrude and Cézanne’s portrait of his wife. Once the Cézanne disappeared, Gertrude said in response to a visitor’s query about it, “We are eating the Cézanne.” Similarly, after Gertrude’s death, Alice sold some of the pictures that had been hidden away in Paris during the war; she needed the money to subsidize the publication of some of Gertrude’s more opaque writings. In Alice’s last years, she became embroiled in an ugly dispute with Roubina Stein, the widow of Allan, Gertrude’s nephew and the co-beneficiary of her estate. Returning one summer to Paris from a sojourn in Italy, Alice found that Roubina had stripped the apartment of its art. “The pictures are gone permanently,” Alice reported to a friend. “My dim sight could not see them now. Happily a vivid memory does.”

Leo never lost the collecting bug. But to hold on to his villa in Settignano, where he lived with his wife, Nina, and to afford their winters in Paris, he, too, had to sell most of the paintings he owned, including all the Renoirs. But in the 1920s and ’30s, he began buying again. The object of his renewed interest was even stranger than Gertrude’s: a forgettable Czech artist, Othon Coubine, who painted in a backward-looking Impressionist style.

Only once, not long after the end of World War I, Gertrude thought she glimpsed Leo in Paris, as she and Alice drove by in their Ford. He took off his hat and she bowed in response, but she didn’t stop. In the more than 30 years between his acrimonious departure and her death, brother and sister never spoke again.

Arthur Lubow wrote about China’s terra cotta soldiers in the July 2009 issue. He is working on a biography of Diane Arbus.