An Opera for an English Olympic Hero

Lal White was forgotten by many, even residents of his small English factory town, but the whimsical Cycle Song hopes to change that

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Cycle-Song-Darren-Abraham-631.jpg)

Big skies, big Scunthorpe skies,

Where the moon hangs in the evening

Shining in the big sky and the air is still

As though the air is waiting for morning

As though the air is waiting for something to move.

Ian McMillan, Cycle Song

You could say Scunthorpe is in the middle of nowhere, but it’s really not that central. Squatting over a rich bed of English limestone and iron ore, Scunthorpe is six miles from Scawby, which is 43 miles from Sleaford, which is 94 miles from Luton, which is 33 miles from London. It’s the sort of drowsy hamlet in which you can get your tank filled at the Murco station, toss back a Ruddles at the Butchers Arms or get buried in Brumby Cemetery.

It was steel that built this self-styled “industrial garden town” and steel that broke it. In its heyday, Scunthorpe’s ironworks was the second largest in Europe, employing 27,000 workers. The Frodingham Iron and Steel Company was later acquired by British Steel, an industrial giant that helped power World Wars I and II. But the industry collapsed in the 1980s and, like many English institutions, continues in decline. Its best years were in the distant past, and there’s no sign of a renaissance.

The plant, now part of an Indian conglomerate, is a battered relic of Britain’s industrial might. These days just 3,750 workers make steel there. Vast portions of the mills have been demolished; many of the great sheds are empty. What remains are four towering blast furnaces named after four once-towering queens: Anne, Mary, Victoria and Bess.

Nothing else in Scunthorpe is quite so...majestic. Which may be why Spike Milligan—the late British comedian whose epitaph, translated from the Gaelic, reads: “I told you I was ill”—gave one of his books the mocking title Indefinite Articles and Scunthorpe. When locals chafed, Milligan said: “We should like the people of Scunthorpe to know that the references to Scunthorpe are nothing personal. It is a joke, as is Scunthorpe.”

The town has few claims to even regional fame apart from the fact that, in 1996, America Online’s obscenity filter refused to allow residents to register new accounts due to an expletive embedded within the name Scunthorpe. No top-tier sports team trumpets its name, no attraction lures drivers from the thoroughfare that runs forlornly through it. Scunthorpe does boast one athletic distinction, though: The cycling pioneer Albert “Lal” White used to live there.

A steelworker who trained between shifts, White dominated English cycling from 1913 to 1926, winning 15 national titles on grass and cinders. His most memorable finish wasn’t a victory, but the Olympic silver he won in the 4,000-meter team pursuit at the 1920 Antwerp Games. He and his brother Charlie also invented the first stationary exercise bike, which they fashioned out of washing machine wringers bought at a corner store. Hence the phrase “going nowhere fast.”

White’s life and achievements are celebrated in Cycle Song, a whimsical English opera with a libretto written last year by an equally whimsical English poet. In mid-July, two outdoor performances of the newly commissioned work will be staged at Scunthorpe’s Brumby Hall sporting grounds, where White once worked out. The premiere coincides with the 2012 London Olympics.

Of the 1,400 townsfolk expected to participate, half are schoolchildren. The production will feature orchestras, marching bands, cyclists, dancers and the Scunthorpe Cooperative Junior Choir, which, in 2008, won BBC3’s prestigious Choir of the Year award.

Choral director Sue Hollingworth was responsible for getting Cycle Song in motion. She hatched the idea last year with James Beale, director of the Proper Job Theatre Company in Huddersfield. Proper Job is best known for presenting large-scale outdoor musicals about Dracula, which featured 1,000 gallons of spurting “blood,” and Robin Hood, which involved a house-size puppet that squashed the wicked Sheriff of Nottingham.

“Originally, I wanted to tell the story of Lance Armstrong,” recalls Beale. “A man who came back from cancer to win the Tour de France six times seemed to exemplify the Olympic spirit. Then Sue told me about the cycling icon right on our doorstep.”

Cycle Song is an epic yarn about a town, an invention and a man’s determination. “Lal White didn’t have a practice facility or any resources behind him, and he competed against athletes who did,” says Tessa Gordziejko, creative director of imove, the arts organization that helped produce the project. “He was a genuine working-class hero.”

Genuine, but forgotten. Before the opera was commissioned, few current denizens of Scunthorpe knew White’s name or his legacy. “Now, almost a century after his most famous race, the town has sort of rediscovered and reclaimed him,” says Beale.

A man is riding through morning

A man is riding through morning

on a bicycle

Catches the light in its wheels

And throws the light round and round.

It’s no accident that in a recent poll of the British public, the bicycle was voted the greatest technical advance of the past two centuries. An alternative mode of transport to the horse, bikes were conceived as time-saving machines that would not require feeding or slurry the streets with scat or die easily.

Early horseless carriages were as fantastical as they were impractical. Among the most wondrous were the Trivector—a coach that three drivers propelled along the road by rhythmically pulling levers—and the Velocimano, a sort of tricycle that moved forward when its leathery wings flapped.

An eccentric German baron named Karl Christian Ludwig von Drais de Sauerbrun invented the two-wheeler in 1818. His “draisine” was a tricked-out hobbyhorse with wooden wheels and no pedals: the rider had to push off the ground with his feet, Fred Flintstone-style.

The first pedal-driven model may or may not have been assembled by Scottish blacksmith Kirkpatrick Macmillan during the mid-19th century. What’s indisputable is that in 1867, two-wheelers —called velocipedes—started appearing commercially under the name Michaux in France. Not to be outdone by their Gallic counterparts, British engineers made improvements. Still, bikes were widely dismissed as novelty items for the wealthy. In his book Bicycle: The History, David Herlihy tells of a Londoner who, encircled by a hostile mob, heaved his velocipede on top of a passing carriage he had frantically hailed, and leaped inside to escape.

To enable greater speeds, British designers made the front wheel bigger, resulting in the extreme of the high-wheeler, known variously as the ordinary or boneshaker or penny-farthing.

You straddled the vehicle at your peril. Because the pedals were attached to a 50-inch front wheel, you had to perch atop the wheel hub in order to simultaneously pedal and steer. And since your feet couldn’t reach the ground to serve as brakes, stopping was problematic. Riding the ordinary proved fatal for some cyclists, who plunged from their seats headfirst.

Bicycle design improved incrementally, achieving mature form by 1885, when an engineer from Coventry—100 miles south of Scunthorpe—introduced the Rover “safety bicycle.” A low-slung contraption, the Rover had a chain-driven rear axle and lever-operated brakes. Its mass production propelled the subsequent bike boom, just as its popularity scandalized Victorian society.

To many Brits, the bike was a symbol of unwelcome social change. They feared the technological innovation would lead innocent young girls astray by encouraging immodest attire, spreading promiscuity and providing sexual arousal. Some fretted that the bike might even prevent women from having children.

The Victorian male was, of course, impervious to ruin or disgrace. Which may explain why by 1905 pretty much every working man in the country owned a bicycle. In fin de siècle Scunthorpe, none rode faster than Lal White.

Training in the snow, riding in the rain

He’s got a bicycle wheel for a brain!...

Punctures in the morning at half past three

He’s got a saddle where his heart should be!...

Pedal through the mud, stumble in a hole

He’s got handlebars on his soul!

Whereas the world-class cyclists of today perform in a professional sport tarnished by illegal drug use and other grown-up foibles, White was an amateur with an almost childlike belief in the ancient verities: courage, perseverance, loyalty, honor, honesty. Once, when challenged while testifying at a trial, White snapped that he never told a lie. The newspaper account was headlined: “George Washington in Court.”

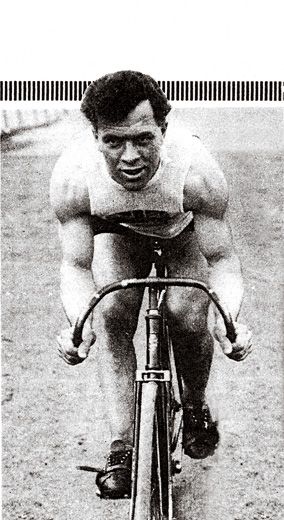

In photographs from his sporting prime, White seems as hard as iron. Thick and solid, his eyes pure bottled fury, he looks as though he’d get the best of a collision with a truck. His muscled forearms are so cartoonishly plump they would make Popeye blush. “Lal’s steely spirit matched the town’s,” says Beale.

White worked at steel mills for 50 years, most of them as a molder in the Frodingham foundry. Molders were the artisans of their day, preparing castings for the crucible pour of molten steel. Their craft was mostly unchanged by the industrial revolution that brought clanking machinery to the workplace. Standing atop a pile of damp sand, White labored in rising heat as white-hot liquid metal was ladled into molds, like lava oozing from a volcano.

You get the distinct impression that White was extremely hard-working and capable of taking infinite pains to achieve precision. The truth is his cycling career was practically a hymn to the work ethic. He accomplished his feats astride a bespoke bike with fixed gears, low-tech even by early 20th-century standards. His refusal to accept limitations became a self-fulfilling destiny.

White was born in Brigg, a market town along the River Ancholme. When he was 5, his family moved down the road to Scunthorpe. His first victory came at his very first race, a contest for boys 14 and under during the 1902 Elsham Flower Show. He was 12.

White had 16 siblings, at least two of whom cycled competitively. He won his first national title—the one-mile tandem—in 1913 with his older brother Charlie aboard. Over the next two decades he won hundreds of medals, cups and watches. He used his prize money to buy a wedding ring for his bride, Elizabeth, prams for his three children and a Cole Street row house. He named the house Muratti after a silver trophy awarded to the winner of an annual ten-mile race in Manchester. Only the top ten riders in the country were invited to compete for the Muratti Vase, which White won outright in 1922 with his third straight victory.

The conquering hero was driven home in a convertible; all of Scunthorpe turned out to cheer him. To be feted by his hometown was not uncommon for White. Once, he got off the train at Doncaster and cycled home, only to learn that a huge crowd of well-wishers awaited him at Scunthorpe Station. Rather than disappoint his fans, he arranged to be smuggled to the terminal by car and suddenly appear when the next train pulled in.

Scunthorpe had no track within 30 miles, no local cycling club. So White improvised. He roller-skated to stay in shape. For speed training, he sometimes raced a whippet for a quarter-mile along Winterton Road. Before long-distance events, he’d enlist as many as 20 racers to pace him in relays. In bad weather, he kept fit on the primitive stationary bike that he and Charlie had rigged up. Two static rollers carried the rear wheel while a ceiling rope held the apparatus in place. To keep their invention from flying out a window, they added a front roller and drive belt, and dispensed with the rope. Which may explain why the White brothers are never confused with the Wright brothers.

In the event that Lal was unable to scrounge up money for a train fare, he’d pedal to a meet, race and then pedal home. When he could spring for a ticket, he had to be mindful of railway timetables. He tried his best to be accommodating, most famously at an event that ran late in Maltby, some 36 miles from Scunthorpe. According to a report of the competition, White “had already won one race, and had led his heat 42 for the last event of the day. He changed into a suit, and was crossing the track with his machine and bag when the judge called, ‘Hey! Where are you going?’ He was told that he must ride in the final, which was just about to start. He put down his bag, mounted his machine and won the final fully dressed.” Then he pedaled home.

White’s championship season was in 1920. On the strength of having won four major races from 440 yards to 25 miles, he was picked to represent Britain at the Olympics in three of the four cycling track events, and as a reserve in the tandem. He won his silver medal in the team pursuit, nearly single-handedly upending Italy’s gold medalists in the final stage. After the race a French cyclist, perhaps upset by White’s tactics, rushed the Englishman and decked him. Unconscious for two hours, White missed the 50-kilometer event. But he recovered and four years later rode in the Paris “Chariots of Fire” Games.

White retired from racing at the precocious age of 42. In later years he ran a confectionery stall in Scunthorpe’s indoor market. He died in 1965, at 75. In 1994, his medals—among them, the Olympic silver—were quietly auctioned off. No one in Scunthorpe seems to know what became of them.

“Scunthorpe is a place where losing comes easy and nothing much is ever achieved,” says Ian McMillan, the Cycle Song librettist. “It’s full of ordinary people not used to winning or doing well. When you get a winner like Lal, his glory reflects back on the town. He’s proof that success can happen here.”

When he cycles the streets we cheer him:

Very soon another cup will be displayed

Shining like summer in his window

He is forged from finest steel:

He’s Scunthorpe-made!

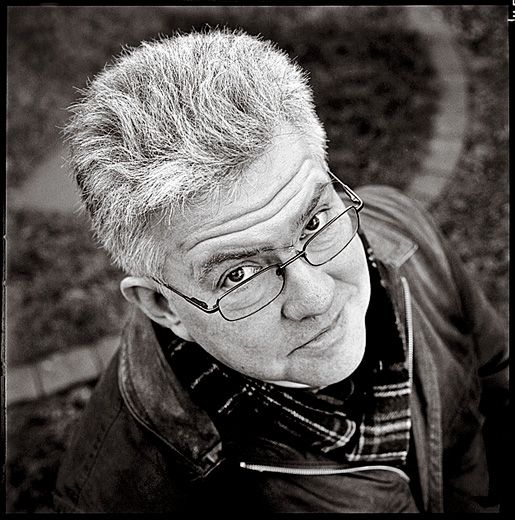

McMillan is an exuberant and relentlessly jolly man, with thickets of gray hair, a reckless optimism and an undepletable fund of anecdotes. A modern-day troubadour who plays schools, theaters and arts centers, McMillan was enlisted for Cycle Song because of his renown as host of “The Verb,” a weekly cabaret of language on BBC Radio 3. Called the Bard of Barnsley, he has published collections of comic verse, including I Found This Shirt; Dad, the Donkey’s on Fire; and 101 Uses for a Yorkshire Pudding. His reputation of never saying no to a job offer has led him down some twisty paths. He’s been poet-in-residence for the Barnsley Football Club, beat poet for the Humberside Police and performance poet for the Lundwood sewage treatment plant.

McMillan’s theatrical oeuvre includes Frank, which envisions Dr. Frankenstein’s monster as a window cleaner, and Homing In, an operetta in which a flock of racing pigeons chorus:

You can see our home from here

You can see me Aunty Nellie with a bottle of beer

You can see me cousin Frank with a sparse comb-over...

Cycle Song—which McMillan calls his “Lal-aby”—provided endless possibilities for assonance. He is particularly pleased with having rhymed peloton with skeleton. “I’m aiming for magic realism,” he says. “And Lal rhymes with magical.”

What McMillan is after isn’t a melodramatic tale, say, about White and his Olympic quest, but something more metaphysically evolved. What interests him is allegory. He savors the symbolism in the way bike wheels move incessantly forward, yet never escape their cyclical nature. “A spinning wheel always comes back to its starting point,” McMillan says. He marvels at how the mathematical symbol for infinity—the figure eight tipped sideways— resembles a bike. “On one level, the bicycle is a kind of life cycle,” he says. “On another, it’s a metaphor for eternity.”

As his opera opens, the setting moon fades into the rising sun over a stage composed of three circular platforms of varying heights. “Bathed in the golden light of dawn, the discs glow like Olympic rings or gold medals,” says McMillan. “The swaying choirs on the upper level effectively become clouds, drifting, drifting. As smoke billows from the stacks of the Four Queens, the deep-red stage lights shine brighter and brighter, almost blinding the audience. We’ve created the Scunthorpe sky. The stage is the Scunthorpe of the mind.”

The scene shifts to a candy store, not unlike the one White ran in Scunthorpe market. A small boy, who may or may not be Young Lal, wanders in. The shop owner, who may or may not be Old Lal, sings the “Song of White”:

This is a town and a dream coinciding

This is a town and a dream colliding

You’re carrying the hopes of a town on

your bike frame

Your wheels are going round

and we’re singing out your name!

In the sharp light, the jagged, vaporous landscape of the steelworks lies calm and hazy blue-gray. Suddenly, 100 cyclists burst through the gate. “The group will move like a giant fish, with each rider a scale,” offers Beale, the director. “I have a recurring nightmare that one cyclist falls, starting a domino effect that topples them all, like in a circus.” And if the dream becomes reality? “In the circus, a trapeze artist plummets from a tightrope,” he says with a small sigh. “Or an elephant stomps a clown. You’ve got to carry on.”

The denouement is set at the Antwerp Olympics. White loses the big race, but wins the hearts of the crowd. “Winning is not the important thing,” says Beale. “Striving is, and Lal was a peerless striver.”

Though White crosses the finish line, he’s not finished. A crane hoists him and his bike into the air. He spirals upward, toward an immense, shimmering balloon—the moon. “Like E.T., he cycles into the sky, the night, the future,” McMillan explains. “Like Lal, all of us have the ability to soar beyond the possible.”

And how will the people of Scunthorpe react to the sight of their beloved steelworker ascending into the heavens? “They’ll weep with joy,” McMillan predicts. There is the slightest of pauses. “Or, perhaps, relief.”

Photographer Kieran Dodds is based in Glasgow, Scotland. Stuart Freedman is a photographer who works from London.