Animal Magnetism

Gregory Colbert’s haunting photographs, exhibited publicly for the first time in the US, hint at an extraordinary bond between us and our fellow creatures

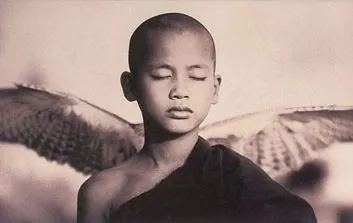

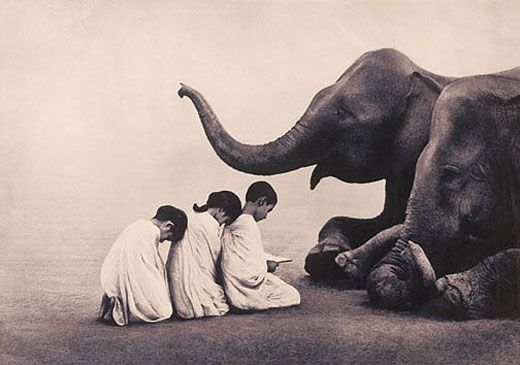

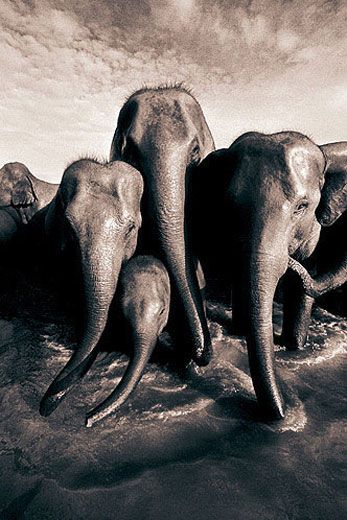

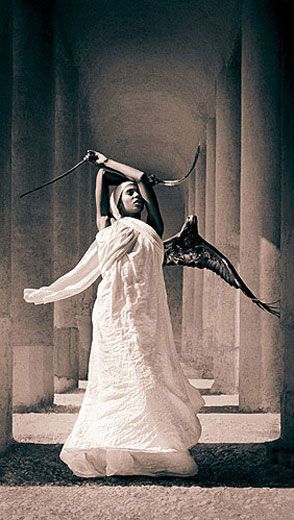

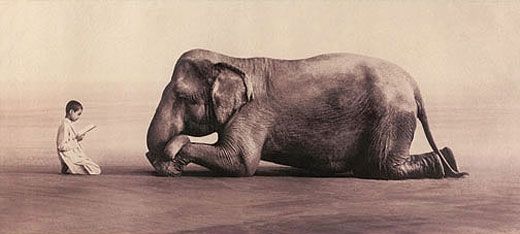

The most arresting aspect of Gregory Colbert's photographs, in his show "Ashes and Snow," is their air of dreamlike calm. That serenity pervades the sepia-toned pictures, though the people in them—children mostly—pose with enormous elephants, flapping falcons, cavorting whales. There's even a shot of a young girl sitting with a big spotted cheetah as peacefully as if it were a pussycat. Surely, you're bound to wonder, were these images digitized, collaged, somehow toyed with? No, says Colbert, 45, a Canadian-born artist and adventurer who has made 33 expeditions in 13 years to photograph people and animals in places from Egypt to Myanmar to Namibia. Directing his human subjects, and often waiting patiently for the animals, he took hundreds and hundreds of pictures, from which those in the show were selected. His ambition is to dissolve the boundaries between man and other species, between art and nature, between now and forever.

If you haven't heard of Colbert before, you're hardly alone. A New York City resident, he has never shown his work in a commercial gallery or U.S. museum but instead has been supported by private collectors, such as Paul Hawken, an entrepreneur, and Patrick Heiniger, the head of Rolex, which helped underwrite this show. (Colbert's photographs start at $180,000 and have been collected by Donna Karan, Laurence Fishburne and Brad Pitt.) For "Ashes and Snow," Colbert commissioned the Japanese architect Shigeru Ban to design a "nomadic museum." This remarkable 672-foot-long temporary structure—made of shipping containers, with trusses and heroic columns constructed of cardboard—was erected on a pier on the Hudson River in Manhattan.

Entering it is a little like going to church: it is darkly dramatic, with the photographs lit and suspended on wires, so they seem to float in the nave-like space. They are stunning as objects, both in their scale—about 6 by 9 feet—and in their soft patina. Printing on handmade Japanese paper, Colbert uses beeswax or pigment to create a sense of age—or perhaps agelessness. The artist, who doesn't wear a watch (not even a Rolex), says, "I work outside of time."

Critics, however, live in the temporal world, and "Ashes and Snow" has drawn fire from, among others, Roberta Smith of the New York Times, who called the exhibition "an exercise in conspicuous narcissism." Partly, she was provoked by a film that accompanies the show, which echoes the photographs but doesn't capture their haunting mood; it plays continuously in slow motion with a portentous voice-over by actor Fishburne. The ponytailed Colbert himself appears in several sequences—dancing with whales, swimming an underwater duet with a girl, looking priestlike in an ancient temple.

The public has embraced "Ashes and Snow," which has drawn more than 15,000 visitors a week since it opened in March. (The show closes June 6 but will open in December on the Santa Monica Pier near Los Angeles, and other venues abroad are planned, including the Vatican.) Colbert considers himself in the midst of a 30-year project and will keep adding to what he calls his "bestiary." Next on his itinerary: Borneo to photograph orangutans; Belize or Brazil for jaguars.

The most striking image in "Ashes and Snow" is unlike any other: an almost abstract close-up of an elephant's eye, bright and piercing, looking out from a mass of wrinkled skin. The human subjects in these photographs keep their eyes closed. Colbert, trying to level the field between man and beast, says he wondered "what it would be like to look out of an elephant's eye." "Ashes and Snow" is his answer. Now we wonder what the elephant would make of this elegantly stylized dream world.