In a former boat repair workshop in Venice, down a narrow alley just off the Grand Canal dead-ending at the water’s edge, hides a space now used as a painting studio with Corinthian columns and skylights overhead. Towering canvases hang on every surface. Many more are stacked like dominoes in the corners. A bloody shade of red, the artist’s signature color, mixed from an oil paint base of alizarin crimson, is pervasive in the abstract work here.

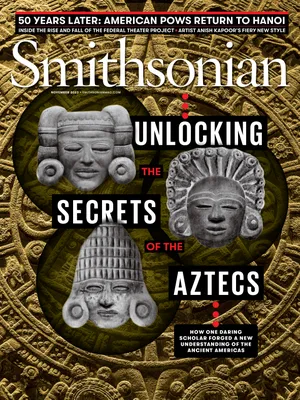

“I’ve used it again and again and again and again,” says Anish Kapoor, the 69-year-old British Indian artist behind this particular hue, chatting in his newly occupied Venice studio in August. Kapoor has spent decades exploring the possibilities of this corporeal color, in three-dimensional objects forged from silicone, wax and other malleable materials and, increasingly, in gobs of thick paint on canvas.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b5/28/b528b246-e1fa-4471-990b-39a54530df9d/dsf4408.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4d/a3/4da38d4d-b3f7-45a2-90d2-df7b43894fd5/nov2023_f14_anishkapoorvenice.jpg)

Kapoor is best known as a sculptor of monumental, abstract, perception-defying works of public art, mirrored surfaces that seem to have no beginning or end, like Cloud Gate, better known as “The Bean,” his apparently seamless 110-ton stainless steel ellipse in Chicago’s Millennium Park, and immersive forms so enormous they consume entire building interiors, like Leviathan, his bulbous PVC balloon installation that filled the Grand Palais in Paris in 2011.

Kapoor has had a decades-long obsession with negative space, with the void—the “non-object,” he calls it—in all its permutations, cutting up museums and galleries with site-specific gashes in the walls and black holes in the floors that seem to have no end.

In 2016, he sealed a deal with British technology firm Surrey NanoSystems for the exclusive use of Vantablack, touted as the blackest substance on earth, a technological marvel developed for scientific and stealth applications and produced in a high-temperature reactor. Kapoor had to sign an agreement under the Official Secrets Act at the British Home Office before he could negotiate a lock on its artistic use.

A number of artists began criticizing Kapoor publicly after news broke of his monopoly on the “world’s blackest black.” British painter Stuart Semple responded tongue-in-cheek by unveiling what he called the “pinkest pink,” offering his fluorescent hue for sale online, but requiring each buyer to first confirm “you are not Anish Kapoor, you are in no way affiliated to Anish Kapoor, you are not purchasing this item on behalf of Anish Kapoor.” Kapoor replied with an image on Instagram of his middle finger drenched in Semple’s “pinkest pink.”

“That silly young fellow,” says Kapoor of his 43-year-old faux nemesis. “I understand the impulse to say, ‘How can a color be exclusive?’ But it isn’t a color.”

Vantablack is not even “a paint,” he explains, but “a highly complicated, bloody difficult, damned expensive technical process, and extremely fragile,” less a color than the absence of it, absorbing light, so that a coating applied in lab conditions makes three-dimensional objects, like a sphere protruding from a cube, appear head-on to be entirely flat. “Is there an object? Is there not an object? Is it real, not real?” says Kapoor of the mystifying work he produced with the material after years of trial and error, unveiling the first pieces at an exhibition in Venice in spring 2022.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5a/81/5a81903f-3470-4d39-a93e-7a806cd74aef/nov2023_f13_anishkapoorvenice.jpg)

Kapoor’s art often requires teams of collaborators to execute, and months—even years—to bring to fruition. Along with the technicians, fabricators and stone carvers employed by his London studio over the years, he’s tapped structural engineers, architects, shipbuilders and mirror-makers, among other experts. As a respite from his laborious collaborative work, in recent years he’s been embracing a more solitary focus on painting, spending hours alone working in his studios in London and Venice.

“Having this physical work that he can make immediately and by himself I think just gives him an energy, an outlet,” says Greg Hilty, partner and curatorial director at Lisson, a gallery in London where Kapoor’s work is regularly on exhibition, “and, also, is a counterpoint to some of the more shiny work, the sublime work. In his mind, they couldn’t exist in the world without each other.”

Kapoor’s canvases sometimes have a three-dimensional quality, jutting out from the surface as they blur the lines between painting and sculpture. They tend to be spontaneous, visceral works, exploring messy, violent, often sexual themes, in brutal abstractions conjuring flesh ripped open exposing viscera and blood, fiery rivers of lava rushing past. A trio of large paintings hanging in the Venice studio feature the outlines of a prone figure gushing torrents of red. “It’s the body, if you like, expunging its interior,” says Kapoor. The piece was inspired, in part, by a late medieval painting he saw hanging in Padua depicting the death of the Madonna.

Still, this high-octane body of work is particularly jarring taken alongside the cold precision of Kapoor’s conceptual sculptures.

“You know there are two sides to Anish, what I call the clean side, the polished side, and then there’s the dirty side, and it was when I saw the dirty side that I understood the clean side as well,” says British curator Norman Rosenthal, former exhibitions secretary of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, who helped organize Kapoor’s first showing there in 2009.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/88/d0/88d00c92-1413-4f47-873c-281177f42d50/dsf4409.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3b/dc/3bdc3d52-53fd-487d-9dee-47d05b10026a/dsf4438.jpg)

Kapoor echoes the sentiment. “There’s this way in which I’ve worked which is very pure, very clean and all that,” he says, of his precise sculptural work. “But I had a feeling there’s something else, which is more essential. I don’t know what the word is, because they’re both essential, in fact. They’re not in conflict, but they are different ways of seeing the world.”

Kapoor was born in Mumbai when it was still called Bombay, in 1954, to a Punjabi Hindu father and a mother of Iraqi Jewish heritage. He arrived in London for art school in 1973. Eighteen years later he won the Turner Prize, Britain’s highest art accolade. In 2013, he was knighted by Elizabeth II for “services to visual arts” in her annual birthday honors.

“I’ve always had a very strange relationship to England and to London,” he says, reflecting on his adopted country, India’s former colonial ruler. “I’ve lived there longer than I’ve lived anywhere else, had my children there, got married there, built too many homes there … it’s a complicated history with England for me—Sir-bloody-Anish, all that crap. So, in a sense you get drawn into the establishment, but at the same time I’ve always felt uncomfortable about it.”

Now, after 50 years living in Britain, Kapoor has begun shifting his center of gravity to Venice. “What I like about being in Italy is, unequivocally, I’m a foreigner and I like that,” he says.

“Venice,” says Hilty, “represents in many ways historically and symbolically an opening up of Europe to the wider world, in some ways a meeting of East and West, kind of like Istanbul. And that’s Anish’s world, really, neither west nor east but some dynamic fusion or dialogue between them.”

In 2018, Kapoor took over the Palazzo Priuli Manfrin, an abandoned Venetian landmark, with layers of history extending back to the 16th century and a grand ballroom overlooking the Cannaregio Canal, announcing his intention to establish a foundation headquarters, a future home for his archive and a new creative hub there. “In very large terms I try to think of it as a working space in which I might leave some works and maybe ask some artists to come and do something else, or use part of it,” he says.

Last year, with restoration work on the building ongoing, he set up his new painting studio across town. This winter he plans to move the studio into a much larger space nearer the palazzo, in a former factory building with room enough to also produce sculpture on-site.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/27/012749d1-b3db-46e4-a415-d7fcc2a75c9c/dsf4445.jpg)

Kapoor has been enthralled with Venice since 1990 at least, when he was chosen to represent Britain at the 44th contemporary art Biennale. The work he showed at the British Pavilion—including Void Field (16 imposing sandstone blocks on the floor) and The Healing of St. Thomas (a red gash in the wall)—won him the Premio Duemila for artists under 35 (even though, controversially, Kapoor had turned 36 by then). “On the day of the opening, I walked into a restaurant, the whole restaurant stood up and applauded,” he says. “That was so touching, wonderful.”

He returned frequently to Venice over the years, showing new work during subsequent Biennales. Eventually he bought an apartment there. “I’ve had this very long association with Venice,” he says. “I’ve always felt it to be good to me, and good to the work. I like that it’s a village and that it’s cosmopolitan. I still have my studio in London, spend roughly half my time between here and there, but I do feel more and more that it’s home, Venice.”

Though works on paper and canvas have always been part of his practice, they’ve become much more of a focus over the last ten years as he’s embraced a new parallel path to his work as a sculptor. “I’ve watched so many colleagues do what they do and then they do what they do. It’s not my road,” he says. “I’m interested in what I don’t know and what I haven’t done. I feel that’s the real mission of the artist.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/04/44/04447b80-4890-49af-b178-15e3900c547f/dsf4491.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a1/a2/a1a267e0-166d-43c7-bb04-23e2420d3e85/nov2023_f11_anishkapoorvenice.jpg)

These days when he’s in painting mode, whether he’s in London or Venice, Kapoor tries to finish a canvas a day. “I’m pretty prolific—I’ve got a hell of a lot of work. I probably let 10 percent out into the world on a yearly basis,” he says. To store it all, recently Kapoor purchased a huge warehouse north of London. Much of the unreleased work there, he says, will be donated to the foundation eventually, so that his children won’t be responsible for managing these portions of his estate after he’s gone—he has a son and two daughters from two different marriages.

Even away from the studio his output is impressive. Along with homes outside London and in Venice, he has places in Harbour Island in the Bahamas and in Jodhpur, India. He produces works on paper at all of the sites, mostly colorful gouache abstractions. There are literally hundreds stashed in drawers at the London studio, categorized based on where they’re made. The Jewish Museum in New York will showcase a few of them in a works-on-paper show next year.

In recent years Kapoor’s paintings have become a much bigger presence in his gallery and museum shows, often presented alongside his precise machine-made sculptural objects. A whole crop of new paintings will make their public debut in November in a broad survey of his new work at the Lisson Gallery’s New York outpost, opening just after Kapoor’s mini-retrospective in Florence, Italy, at the Palazzo Strozzi art space.

By now Kapoor has begun mastering the bewildering maze of pedestrian roads and bridges that snake through the Venice canals. “I’m mostly successful in finding ways of going through the back streets where there aren’t thousands of tourists,” he says as we cut across town for a late lunch in August.

When he bought the sprawling Palazzo Priuli Manfrin from the local government—which lacked the funds to restore it—he had little idea what he’d do with the space. Curator Mario Codognato, a Venice native and old friend of Kapoor’s from his early days as a young artist in London, first introduced him to the building.

Codognato, the former chief curator of the MADRE contemporary art museum in Naples, where he often showed Kapoor’s art, has been working on the renovation ever since, after signing on as director of Kapoor’s new foundation. “The project grew so organically,” says Codognato, who first suggested basing the foundation in Venice. Initially, he found a smaller site for the headquarters inside an existing art foundation before hearing about the Palazzo Priuli Manfrin.

Over the last 20 years some of the most important palazzos in Venice, historic landmarks once occupied by the city’s most powerful families, have been snapped up by deep-pocketed buyers, among them some of the world’s biggest contemporary art collectors, who’ve opened them up to the public as private museums—showcases for their art foundations—adding bookshops, ticket offices and sleek new gallery spaces. French fashion tycoon François Pinault runs two outposts of his Pinault Collection, at the Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana. The Prada Foundation also has an art space in Venice. And billionaire investor Nicolas Berggruen is finishing up work on two more foundation spaces, including the 18th-century Palazzo Diedo near Kapoor’s foundation.

“The thing about all these foundation buildings, and there are more and more of them, is that they are done to the nines; they are really done. I want to do exactly the opposite,” says Kapoor. “I don’t want to touch it, or hardly touch it.”

Kapoor scrapped early plans from a local architect, Giulia Foscari, for a bookshop and café on the ground floor, preferring to leave the whole site open-ended for now, with simple infrastructure upgrades. “There will be beautiful rooms to show works in, to make works in … and then we’ll see,” he says.

Kapoor hopes to preserve the sense of decay in the space, cleaning up the 18th-century frescoes and other decorative elements left behind over the years but not changing much else. “I don’t want restoration; what I want is conservation,” he says.

The palazzo was in decent shape when Codognato first found it. Kapoor, an astute student of history, says he was drawn to the building with its soaring double-height ballroom before he learned of its role in the history of art in Venice.

The first portions of the building were completed in the 16th century, when it was home to the aristocratic Priuli family, who produced three doges, the rulers of Venice. In the late 18th century, the palazzo underwent upgrades under a new owner, Girolamo Manfrin, a social-climbing tobacco merchant who burnished his reputation as a tastemaker by opening up his home, and its important collection of art, to prominent figures of the day.

“Mr. Manfrin was a great art collector. He had everything from Giorgione’s La Tempesta to various Rembrandts, all sorts of magical stuff, which I didn’t know when we were negotiating for the building,” says Kapoor.

After Manfrin’s death in 1801 or 1802 (questions remain about the exact year), some of his collection wound up eventually at the Gallerie dell’Accademia, one of the most venerable art institutions in Venice. Over the years Manfrin’s palazzo went into decay. Catholic nuns moved in for a time in the 1900s. The building, though, had been empty for years by the time Kapoor stepped in.

Work has gone slowly in the five years since he first saw the site. “Doing anything in Venice is a nightmare,” he says of the bureaucracy. A completion date for construction still hasn’t been set. “It is an artist’s project,” says Codognato, “so, in a way [it’s] permanently in progress.”

In a full-circle moment during last year’s Biennale, Kapoor was invited to exhibit his own work among Manfrin’s collection at the Gallerie dell’Accademia, as part of an ongoing program showcasing contemporary art. Though Manfrin’s palazzo was still a work in progress, he decided to put renovations on hold so he could also show work there. “We did this folly of expanding the exhibition into this half-destroyed, half-not building,” says Codognato. “The fire brigade were not enthusiastic about it. We had to do a lot of work to make them happy.”

Kapoor filled the ballroom with heaps of red wax, part of a theatrical installation, Symphony for a Beloved Sun, he’d shown years earlier in Berlin. Concave mirror works, turning the world upside down, were displayed under an 18th-century fresco of Medusa. “Obviously, she has to have the mirror,” says Kapoor, of the choice of backdrop.

Though the show closed in October of last year, there are a few remnants in the building as we tour the palazzo. Mount Moriah at the Gate of the Ghetto, an inverted mountain of silicone and red paint that had anchored the entry, lies partially dismantled. The piece, referencing the historic Jewish ghetto of Venice—the main entrance is just across the canal—might be reinstalled after the renovation is done.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/42/6142f78e-27d3-4e31-ad48-f65cfc5cfad1/dsf4280.jpg)

Fractal towers of powdered pigment were removed, part of another piece from the Kapoor archive, White Sand, Red Millet, Many Flowers, leaving behind colored outlines on the floor. “It’s the absent work,” says Kapoor as we walk through the space. The piece, which dates back to 1982, is a variation on his early breakout pigment series, 1,000 Names, which was inspired in part by the colors of India following his first return trip after art school in the late 1970s.

“I went with my parents, my brothers and my wonderful girlfriend at the time. We just traveled—architecture, temples, all that business,” he says. “I saw stuff, felt connected, and then I came back from that trip and a few months later I began to make my first pigment works.”

Kapoor, the eldest of three brothers, was born into a well-heeled Indian family six years after the country won independence from Britain. His father, a hydrographer, in charge of map-making in the Indian Navy, encouraged his sons to follow in his footsteps with professional careers. Kapoor’s mother, an amateur dressmaker, cantor’s daughter and “Sunday painter,” was more open to her eldest son’s artistic interests. She made copies of works by Henri Matisse, he says. “I would finish them for her, and go off in a different direction, start with Matisse and then go somewhere else.”

When Kapoor was a teenager, his family moved to the foothills of the Himalayas, where he and one of his brothers attended one of India’s most prestigious private academies, the Doon School, the country’s answer to Eton, the elite British boarding school. Kapoor, who is dyslexic, says he “hated every single second of it. I was a terrible, terrible student, terrible at sports, a complete slacker.”

At 16, Kapoor and his brother Roy, who is a year younger, were dispatched on their own to Israel, which was offering residency to Indian Jews. “My mother was obsessed with getting us out of India,” he says. With the country struggling through a population surge and conflict with neighboring Pakistan, she hoped for a better life elsewhere.

Kapoor finished high school on a kibbutz south of Haifa and then, in a bid to make his father happy, began studying engineering at the University of the Negev (now Ben-Gurion University) in southern Israel. “I did six months. … I just couldn’t deal with it,” he says. After dropping out, he returned to the kibbutz for a bit of soul-searching. “I decided, in the midst of all my inner turmoil, I was going to be an artist,” he says.

When an art school in Jerusalem rejected his application, he hitchhiked across Europe with a Swedish friend, starting in Istanbul, en route to a new life in London.

It was the early 1970s, a time of creative and political ferment in England. Kapoor enrolled at the Hornsey College of Art in London, where he found a sense of belonging. “For the first time in my life I felt free,” he says.

The school was a hotbed of radical ideas and experimental art. Marina Abramović, then a pioneering young performance artist, was a visiting tutor. Artist Paul Neagu, a mentor on the faculty, encouraged Kapoor to think conceptually. “It really gave me the sense that being an artist, or being an object-maker, wasn’t necessarily about the object; it was about propositions through the object,” he says. “Paul didn’t use those words at all, but he worked in a way that prompted that kind of thinking for me.”

After graduation, Kapoor’s work quickly attracted attention. In 1982, when he was 28, he showed his first pieces in Venice, in the Aperto section of the Biennale devoted to young artists. “I showed next to Julian Schnabel, who put all his work in my space. We had an almighty brawl. It wasn’t very nice, but in retrospect it’s very funny,” recalls Kapoor with a laugh. “We’ve since become friends.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/42/c342de08-c0b9-4c82-89b8-34a256d0ea91/nov2023_f02_anishkapoorvenice.jpg)

But it was representing Britain at the Biennale eight years later that pushed his career into the stratosphere, opening the door to the technically challenging monumental work that followed. “Then in the art world—it’s gone now—there was strongly a sense that just because it’s big doesn’t mean that it’s good, and if it’s big, it’s probably crap,” he says. “And I tried to jump in with both feet, to take on the idea that scale is properly, fully a tool of sculpture, that we must not be embarrassed by it.”

In 1999, Kapoor beat out Jeff Koons to win the commission for a public sculpture in Chicago’s Millennium Park with his proposal for Cloud Gate. “Everybody said a mirrored object of this scale, it’s impossible, can’t be done,” he says. In the six years it took to complete, the budget for the 66-foot-long, 33-foot-high funhouse mirror spiraled from $8 million originally to $23 million by the time it was completed in 2005, receiving a rapturous welcome from the public as it helped usher in the selfie era as one of the first truly viral works of public art.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fe/8f/fe8f2b4f-c00a-4c19-ad52-a751bbff0a05/nov2023_f15_anishkapoorvenice.jpg)

“When it first opened there were thousands of people, and, as ever, I go, ‘Oh no, what have I done? Disneyland, it’s so popular,’” says Kapoor. “And so, I decided to go to Chicago and sit with it, and I sat with it for two or three days, and I realized something. Going back to scale, I realized it’s a big object and not a big object, a big object and a small object. It has no joints at all; you can’t tell how big it is. When you’re near it, it’s enormous, and when you step back from it, it’s not that enormous. The shifting scale felt to me, in my terms at least, there’s a poetic quality to it. And for me that saved it.”

Kapoor’s work hasn’t always gotten such a warm response. In 2015, he unveiled a series of site-specific installations in the gardens of the Palace of Versailles outside Paris. Dirty Corner, a 200-foot-long biomorphic Corten steel funnel that seemed to erupt from the earth, was quickly maligned in the French press—the Le Figaro newspaper dubbed it the “queen’s vagina”—and marred by vandals who covered it in antisemitic graffiti. “I think it was an inside job,” says Kapoor, who met with French President François Hollande, eventually, to discuss the defacements.

Kapoor has been outspoken on many issues over the years—as a frequent fixture in the British press, he has used his stature to campaign against Brexit; rail against India’s Hindu nationalist prime minister, Narendra Modi; and advocate for refugees in the global crisis. Still, he has often said his work, as an artist, has nothing to say. “I don’t set out to make political message art. Agitprop is agitprop, doesn’t make great art,” he says. His abstractions, though, are deeply rooted in art history and in heady metaphysical notions, referencing the avant-garde ideas of early conceptual artists like Russian Kazimir Malevich and Frenchman Marcel Duchamp.

Still, there’s sometimes a prankster quality to Kapoor’s more provocative work. “I quite like being naughty and controversial,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/43/3343d2e5-382e-45cd-904d-712a53e4c9e5/nov2023_f12_anishkapoorvenice.jpg)

His 2007 piece Svayambhu, which in Sanskrit means “self-made,” features ten tons of red wax and Vaseline paint on a track. The piece, tailored to the space where it’s shown, squeezes through doorways, splattering violent red streaks on the walls as it goes. It made a proper mess of the 19th-century galleries at the Royal Academy of Arts when it was installed there in 2009, squeezing through five separate doorways.

A critic in the Guardian, praising the show as “exhilarating,” “self-critical,” “funny and uncomfortable,” wrote that the piece transformed the Royal Academy galleries into “a kind of alimentary canal, an intestinal tract.”

The piece, which has continued to wreak havoc on museum galleries, traveled to Florence in October for Kapoor’s show at the Palazzo Strozzi before it continues on to the United States next year for a planned retrospective at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The work started with a simple notion of creating a form by pushing something through something else, before layers of meaning began to gel on top. “Suddenly it becomes a train, and all the associations with it, being blood—you know, blood-red—associations to everything from the Holocaust to, all kinds,” says Kapoor. “I think that’s the quality of the work: its ability to accumulate to itself layers of meaning.”

:focal(1800x1200:1801x1201)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/be/32/be32cabb-fbfd-4a30-90a4-a3fc5c9674f3/kapoor_new_opener.jpg)