Anne Truitt’s Artistic Journey

Balancing the two lives of a Washington, D.C. sculptor—1950s hostess and emergent artist

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Anne-Truitt-in-Twining-Court-studio-631.jpg)

“The light is wonderful in Washington, [D.C.]” said artist Anne Truitt in an interview near the end of her life. “I have a lifetime of friends here. It’s the latitude and longitude I was born on.”

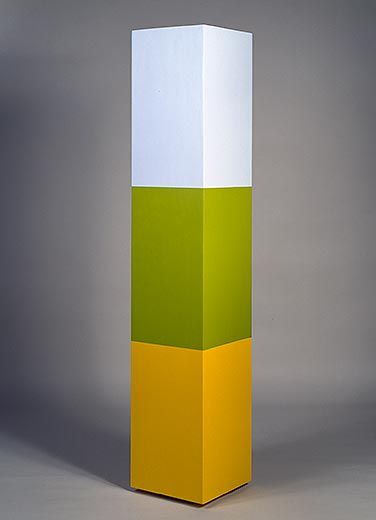

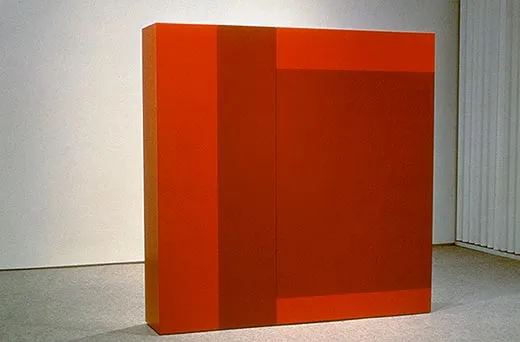

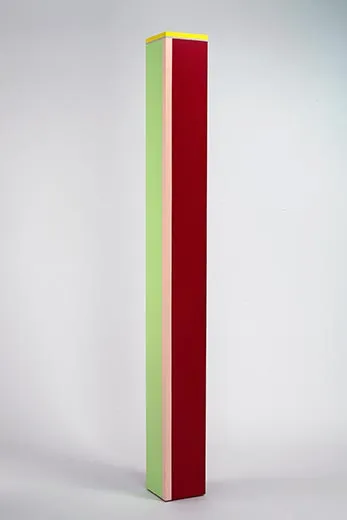

Truitt, largely known for her richly hued columnar sculptures and often associated with Minimalism and the Washington Color Field, claimed the city as her home for more than 50 years. “It’s as if the outside world has to match some personal horizontal and vertical axis,” she wrote in Daybook, the first of three autobiographical journals she published during the 1980s and 1990s. “I have to line up with it in order to be comfortable. … I place myself in Washington, almost precisely on the cross of latitude and longitude of Baltimore, where I was born, and of the Eastern Shore of Maryland where I grew up.”

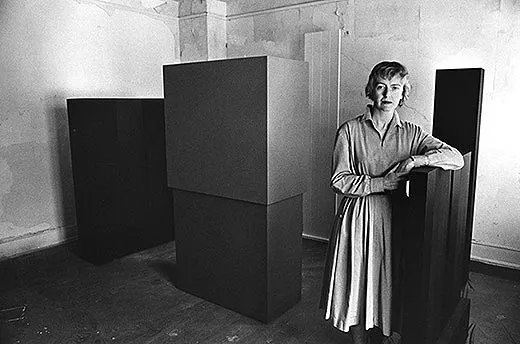

The first retrospective of Truitt’s entire 50-year career, on display from October 8 until January 3 at the Hirshhorn Museum, features more than 80 abstract sculptures, paintings and drawings that never fully meshed with the critics’ definitions, nor brought Truitt the notoriety enjoyed by peers like Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis and Donald Judd.

Although some critics contend that she might have become a bigger star had she moved to New York City, Truitt knew Washington was where she did her best work. It was a place to which she returned again and again with her husband, journalist James Truitt, between his stints working in Texas, New York, California and Japan for Life, Time, Newsweek and the Washington Post. Her years with James in the Kennedy era were a blur of endless socializing with journalists, artists, politicians and other Camelot-era officials.

After their marriage ended in 1969, she lived a quieter life. She bought a house in Washington’s Cleveland Park neighborhood, where she raised her three children, built a studio and made sculptures until her death in 2004 at age 83.

Truitt prized continuity, and like Washington, her artworks provided another sort of axis for her life. For Truitt, they were objects that existed outside the linear progression of her life, objects that embodied her physical and emotional encounters with people, places and other works such as literature. “She came to feel that sculpture for her was a way that time essentially stood still,” says Kristen Hileman, associate curator at the Hirshhorn. Truitt initially started out writing fiction, but became frustrated with the conventions of the narrative, she says.

“One day I was standing in the living room of our house on East Place in Georgetown, a lovely, sunny little living room, and I thought to myself, ‘If I make a sculpture, it will just stand up straight and the seasons will go around it and the light will go around it and it will record time,’” Truitt said in a 2002 oral history interview conducted by the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art. “So I stopped writing and I called up the Institute of Contemporary Art and I enrolled myself, and I began in January and studied for one year. That’s all the art training I ever had.”

The Formative Years

Before moving to Washington, Truitt lived and worked in Boston for several years. A graduate of Bryn Mawr College, she had declined an invitation to pursue a Ph.D. in Yale’s psychology department after realizing she preferred working directly with people. Truitt worked by day in the psychiatric lab at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital and, at night, as a nurse’s aide. Without her experiences in nursing, she said, she would never have become an artist. The work cultivated in her a kind of physical empathy for others.

“The more I observed the range of human existence—and I was steeped in pain during those war years when we had combat fatigue patients in the psychiatric laboratory by day, and I had anguished patients under my hands by night—the less convinced I became that I wished to restrict my own range to the perpetuation of what psychologists would call ‘normal,’” Truitt wrote in Daybook. “And in the light of what I was reading—D.H. Lawrence, Henry James, T. S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf—I had begun to see that my natural sympathies lay with people who are unusual rather than usual.”

Yet her work as a nurse’s aide was not her first encounter with pain and sickness. Born into an affluent family, she spent her first decade happily exploring the shore near Easton, Md. She and her younger twin sisters were taught by a private teacher and her Radcliffe-educated mother regularly read to them. But when Truitt was 12 years old, the Depression ravaged the family income and her parents’ health began to decline. Mr. Truitt struggled with alcoholism and depression and her mother was diagnosed with neurasthenia, characterized by chronic fatigue and weakness. The young Anne was often responsible for running the household.

She and her sisters spent one year with an aunt and uncle in Charlottesville, Va., and then joined their parents in Asheville, N.C., where their father was undergoing treatment and where Truitt felt “exiled.” She entered Bryn Mawr at age 17, but at the end of her first semester, she almost died when her appendix burst during a visit to a friend’s house on the Eastern Shore.When her family’s finances plummeted further, a scholarship saved her from having to drop out of college. The next year, Truitt’s mother was diagnosed with a brain tumor, and Truitt spent many hours on the train between Pennsylvania and Asheville until her mother died later that year.

Truitt would later distill these places, events and memories into her work. She believed experiences—particularly difficult or painful ones—were “the ground out of which art grows,” as she said in her oral history interview. “People talk as if art were something that you did with your eyes and your brain, but it’s not. It’s something that grows out of a ground.”

Life in Washington, D.C.

Truitt arrived in Washington with her new husband in 1947, and the experience of moving to into the city’s upper social circles felt like moving into a shoebox, she said. “I could not believe the consistency,” she said in 2002. “I guess it was…the fact that everybody was so well taken care of and there was a certain level of everybody being the same. They’d all been educated. The women had never worked. So I simply rode on top of all my experience. I didn’t mention it. I never talked about myself, for one thing. Of course, it’s not polite to talk about yourself.”

Her husband James initially worked for the U.S. Department of State, and many of the Truitts’ friends were in the CIA, including top official Cord Meyer and his wife Mary Pinchot Meyer, an abstract painter with whom Anne once shared a studio. “I was floating around in that world…I didn’t pay attention to what was going on. And remember, much was secret. People were covert,” she told art scholar James Meyer in a 2002 interview published in Artforum.

James became Washington Bureau Chief of Life and then vice president of the Washington Post. Through his position and Anne’s involvement with the Institute of Contemporary Art, the Truitts regularly entertained the towering figures of their time, including Truman Capote, Marcel Duchamp, Clement Greenberg, Isamu Noguchi, Hans Richter, Ruffino Tamayo and Dylan Thomas.

A Turning Point

It was in 1961 that Truitt experienced an artistic turning point while viewing the work of Ad Reinhardt, Barnett Newman and Nassos Daphinis in the exhibit “American Abstract Expressionists and Imagists” at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. The works “Reverse[d] my whole way of thinking about how to make art,” she wrote in Prospect, the third of her published journals. Instead of waiting for art to emerge out of material, she realized she could, like these artists, take control of the material to render visible her own ideas.

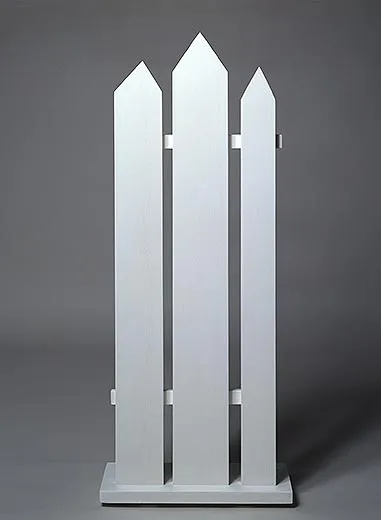

“I was so excited that night in New York that I scarcely slept,” she wrote. “I saw too that I had the freedom to make whatever I chose. And, suddenly, the whole landscape of my childhood flooded into my inner eye: plain white clapboard fences and houses, barns, solitary trees in flat fields, all set in the wide winding tidewaters around Easton. At one stroke, the yearning to express myself transformed into a yearning to express what this landscape meant to me…”

Soon after, Truitt made First, a wooden sculpture that resembled a white picket fence. She also made more room for her work amidst her husband’s social engagements and her children’s needs, and she invested the money she had inherited from her family in her career. There weren’t many women artists of her stature and seriousness that were also wives and mothers, says James Meyer, a professor of art history at Emory University. Truitt didn’t have to get rid of everything else in her life to make her art, nor was she a dabbling amateur, he notes.

Over time, Truitt began constructing more abstract, vertical wooden forms covered in dozens of layers of paint. She had her first show at the André Emmerich Gallery in New York in 1963. Critic Clement Greenberg deemed her a forerunner of the Minimalist movement. But while minimalist artists sought to purge their work of meaning and strip their work down to its most fundamental features, Truitt tried to fill her work with meaning and trigger emotional associations in viewers, says the Hirshhorn’s Kristin Hileman. As Truitt explained in a 1987 Washington Post interview: “I have never allowed myself, in my own hearing, to be called a minimalist. Because minimal art is characterized by nonreferentiality. And that’s not what I am characterized by. [My work] is totally referential. I’ve struggled all my life to get maximum meaning in the simplest possible form.”

She was very protective of her art, says James Meyer. “She would defend her art very intensely if it were exhibited wrongly or she felt it was misunderstood.” Truitt was particularly frustrated when critics—nearly all men in the 1960s—connected the form and content of her work to her gender. She was once described in an article as the “gentle wife” of James Truitt.

An Artist’s Life

The end of Truitt’s marriage in 1969 “set me free to examine and reexamine my own standards, to reaffirm some, discard some and to form new ones for myself, and for my family,” she wrote in Turn, her second book. On the day her new house became hers, she says, “I opened my own front door with my own key, and went straight out to the ground behind the house and lay down on it, among the tall May grasses, knowing it was mine.”

To make ends meet, she taught at the University of Maryland, first as lecturer and then professor, and incorporated art history and literary and philosophical context into her classes. She gave college-wide lectures on contemporary art and was honored as a “distinguished scholar-teacher. Truitt fell in love with teaching and remained with the university for 21 years, enriched by “seeing students go out into the world.”

Truitt became a regular at Yaddo, an artists’ colony in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., where she served as acting director in 1984. And she began to follow a non-sectarian spiritual practice that originated in India. Her vegetarian diet, abstinence from alcohol and meditation bore little resemblance to her social life 20 years earlier.

Neither did she participate in the city’s art scene. Photographer John Gossage, who became friends with Truitt when she used a studio in the same building as his, says she didn’t fit in with the “macho male” bohemian art bar world. With her old-school, Bryn Mawr manners, she came across as more of an art historian, he says.

She was proud of how she successfully balanced work and family life and insisted it was possible for women to have both. “You just have to make up your mind to do it,” she said. “It has to be valuable enough to you for you to work harder, get up earlier, go to bed later, keep your temper.” With a Guggenheim Fellowship, she built a small fisherman’s shack studio in her backyard, just steps from where she raised her children.

Yet she acknowledged that the energy her work required left little room in her life for anything but her family. “It’s the human experience that is distilled into art that makes it great,” she said in the oral history interview. “It’s very difficult to do. It’s difficult to hold the line and it’s difficult to stay true, true in very many ways. True to yourself, true to your experience so you don’t lie about it, don’t fudge it. … It’s extremely difficult and you have to make sacrifices. …You can’t have it all. You can’t. In a way, you can’t have much of a personality or anything because everything has to go into your work. So often you just look dull.”

“Do you feel that about yourself?” asked the interviewer. “Oh, yes, I think I’m very boring,” she replied.