Apollo 15’s Al Worden on Space and Scandal

The astronaut talks about his lunar mission, the scandal that followed and the future of space missions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-QA-Al-Worden-631.jpg)

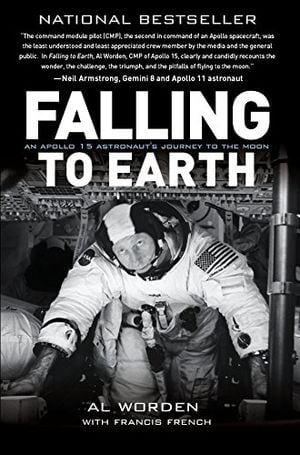

Shortly after his return to earth in 1971, Apollo 15 astronaut Al Worden found himself mired in scandal—he and his crew had sold souvenir autographed postal covers they had taken aboard their spacecraft. As a result, they were banned from ever flying in space again. Recently, Worden was at Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum to sign his new book, Falling to Earth, about his lunar mission and the ensuing scandal. He spoke with the magazine’s Julie Mianecki.

Apollo 15 was the first mission to use the lunar rover, to conduct extensive scientific experiments in space, and to place a satellite in lunar orbit, among other things. What is your proudest accomplishment?

Interesting question. God it was all so great. It’s hard to pick out any one thing. But I would say doing the orbital science—we did everything. The thing that was most interesting to me was taking photographs of very faint objects with a special camera that I had on board. These objects reflect sunlight, but it’s very, very weak and you can’t see it from [Earth]. There are several places between the Earth and the moon that are stable equilibrium points. And if that’s the case, there has to be a dust cloud there. I got pictures of that. I photographed 25 percent of the moon’s surface, which was really kind of neat. And also took mapping camera pictures of the moon for the cartographers.

You spent approximately 75 hours in the command module alone, isolated from even NASA as you went around the far side of the moon. How did you keep yourself entertained?

I didn’t really have to worry about it too much because I didn’t have a chance to think about it very much. I only slept about four hours a night when I was by myself; and that was because I was really busy. But when I wasn’t busy, I was looking out the window taking it all in. It was hard to go to sleep, because there’s a certain amount of excitement involved in it, and there’s also the thought that we’re only going to come this way once, we’re never going to do it again, so we better do all we can while we’re here. So, I was busy 18 hours a day doing science stuff, and I was kind of looking out the window for another two, three, four hours each day, just taking it all in, which was great. The greatest part of it all, of course, was watching the Earth rise. Every time I came around the moon I went to a window and watched the Earth rise and that was pretty unique.

When you did get a chance, what kind of music did you listen to?

I took a collection of tapes with us on the flight and we had a lot of country western, but I was pretty much into the Beatles back in those days, so I carried a lot of Beatles music, and then I carried some French music, a French singer Mireille Mathieu, I carried some of her music too, and then we also carried the Air Force song and some others. Didn’t play it a whole lot on the flight because we were so busy but it was fun to have it there.

Falling to Earth: An Apollo 15 Astronaut's Journey to the Moon

As command module pilot for the Apollo 15 mission to the moon in 1971, Al Worden flew on what is widely regarded as the greatest exploration mission that humans have ever attempted. He spent six days orbiting the moon, including three days completely alone, the most isolated human in existence.

You performed the first deep-space extravehicular activity, or space walk, more than 196,000 miles from Earth. Was it frightening to work outside of the spacecraft?

It wasn’t really because it’s like anything that you learn. You practice it and practice it and practice it to the point where you don’t really think about it very much when you’re doing the real thing. I had a lot of confidence in the equipment and Dave and Jim back in the spacecraft. So it was fairly easy to do. But it was pretty unusual to be outside the spacecraft a couple hundred thousand miles from Earth, too. It’s dark out there. The sun was shining off the spacecraft, and that’s the only light I had, the reflected light. So it was different. You’re sort of floating out there in a vast nothingness, and the only thing you can see and touch and grab a hold of is the spacecraft. But I wasn’t going to go anywhere, I was tethered to the spacecraft, so I knew I wasn’t going to float away. So I just did what I had to do, went hand over hand down the handrails, grabbed the film cartridges, brought them back and went back out again and just stood up and looked around, and that’s when I could see both the Earth and the moon. It was a problem with the training, I had trained so well that it didn’t take me any time to do what I had to do, and everything worked out okay, and when I was all done, I thought, “Gee, I wish I had found something so that I could have been out there a little longer.”

Previous astronauts had taken objects into space that later found their way onto the market. Why was the Apollo 15 crew singled out for disciplinary action?

Those postal covers were sold a couple of months after the flight and quickly became public knowledge. So, I think NASA management felt they had to do something. There had been a similar incident the previous year, when the Apollo 14 crew allegedly made a deal with Franklin Mint to bring silver medallions into space. But NASA kind of smoothed that over because the [astronaut] involved was Alan Shepard, (the first American in space] who was a little more famous than we were. The government never said that we did anything illegal, they just thought it wasn’t in good taste.

After leaving the Air Force, you ran for Congress, flew sightseeing helicopters and developed microprocessors for airplanes. What are you going to do next?

Right now obviously you guys at the Smithsonian have got me busy running around the world, that’s going to take a few months. I’m thinking when this is all over that I might finally, actually retire. I’ve done that a few times and I’ve never been very happy in retirement. So I always go out and find something else to do. I retired the first time in 1975 from the Air Force, and I’ve retired three times since then. I’m just one of those people. I just have to find something to do. So I don’t know, I don’t have anything specific in mind right now, except my wife and I are making plans to build a house on a lake up here in Michigan, get our grandkids here, get a boat and teach them how to water-ski and stuff like that. So that’s kind of our plan right now.

What are your reactions to the end of the space shuttle program?

It’s really sad. The space program is exactly the shot in the arm this country needs—not just from the standpoint of going somewhere, but in developing the technology to go there, and in providing motivation for kids in school.

What advice would you give to young people who wish to pursue a career in space?

The opportunity’s still there. I think there are going to be several avenues for young people to follow. One is in the private sector, because I do believe the private sector will be able to do some things in space. I don’t know about going into Earth orbit. I think that’s a long shot. But there’s a lot of other things that need to be done in space. I think there is just a great need for scientists to look at the universe, not necessarily flying in space, but looking at objects in space, and figuring out what our place is in the universe.

Where do you stand in the debate over manned versus unmanned space exploration?

We can find out a lot about other planets by sending probes and robotic rovers. But, ultimately, you’ll need people on site who can evaluate their surroundings and quickly adapt to what’s going on around them. I see unmanned exploration as a precursor to manned exploration—that’s the combination that’s going to get us where we want to go the quickest.

You grew up on a farm in rural Michigan. What motivated you to become an astronaut?

I won’t say that I was really motivated to be an astronaut when I was young. In fact, I was the only one working the farm from the time I was 12 until I went off to college. And the one thing I decided from all that—especially here in Michigan, which is pretty hardscrabble farming—was that I was going to do anything I could so that I didn’t end up living the rest of my life on a farm. So that kind of motivated me to go to school, and of course I went to West Point, which is a military school, and from there I went into the Air Force and followed a normal career path. Never really thought about the space program until I had graduated from the graduate school at Michigan back in 1964, and I was assigned to a test pilot school in England, and that’s when I first started thinking about being an astronaut. I was following my own professional line, to be the best pilot and best test pilot I could be. And if the space program ended up being something I could be involved in then that would be fine, but otherwise I was very happy doing what I was doing. They did have an application process and I was able to apply and I did get in, but I can’t say it was a driving force in my life.

Astronauts are heroes for many people. Who are your heroes?

My grandfather would be first, because he taught me responsibility and a work ethic. Then there was my high school principal, who got me through school and into college without costing my family any money. Later in life, it was Michael Collins, who was the command module pilot on Apollo 11. Mike was the most professional, nicest, most competent guy that I’ve ever worked with. It was amazing to me that he could have gone from being an astronaut to being appointed the first director of the new Air and Space Museum in 1971.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.