Around the Mall: Old Documentary on Western Tribes Restored

How a Film Helped Preserve a Native Culture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/pastprologue_dec08_631.jpg)

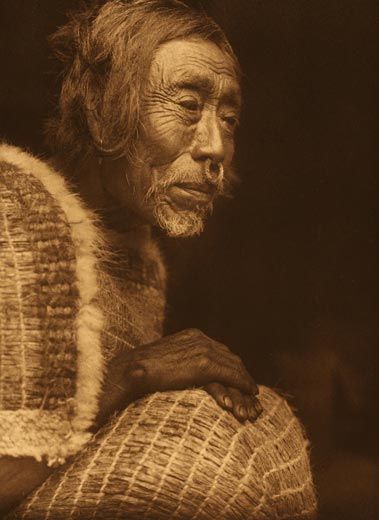

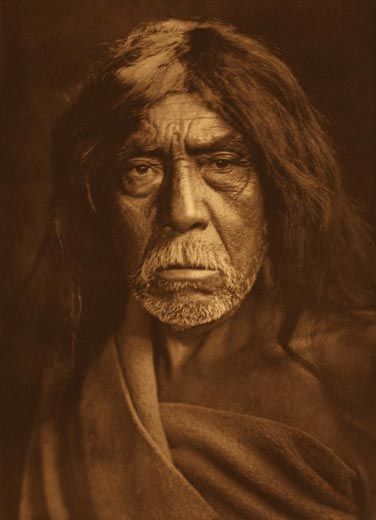

Seattle-based photographer Edward Curtis had a singular passion. Beginning in the 1890s, he set out to document what he and most of his contemporaries believed was a "vanishing race"—that of the American Indian.

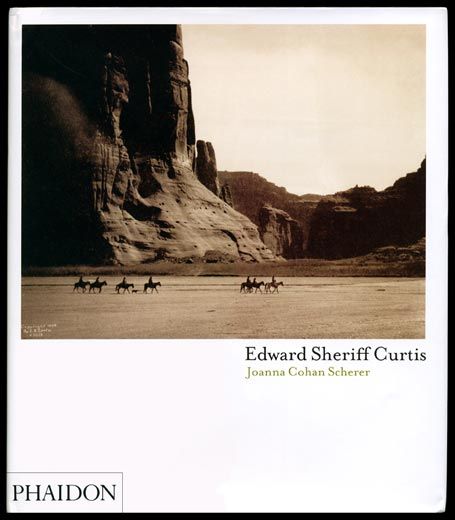

For 30 years, Curtis traveled across North America taking thousands of pictures of native people, often staging them in "primitive" situations. "There were many groups of what were considered exotic people living in North America, and he wanted to romantically and artistically render them as they existed in a traditional past," says Joanna Cohan Scherer, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and author of a new book of Curtis photographs. "Without question he is the most famous photographer of Native Americans from this period."

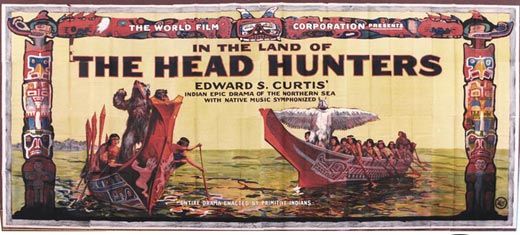

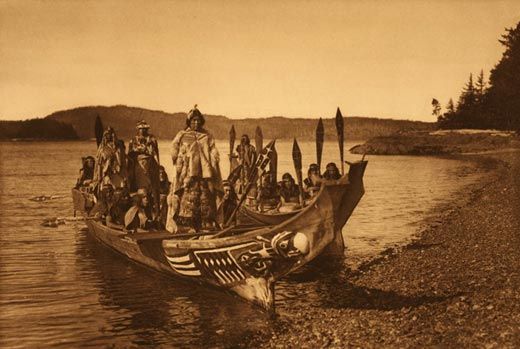

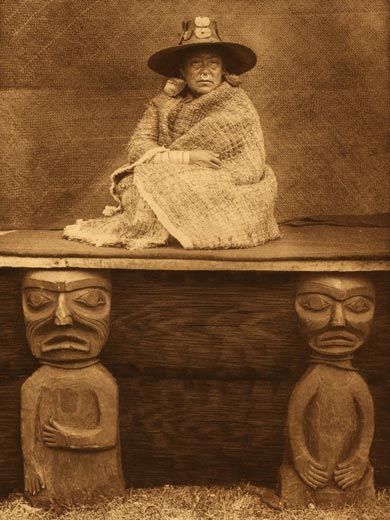

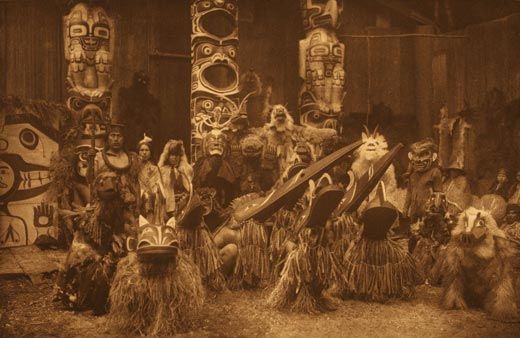

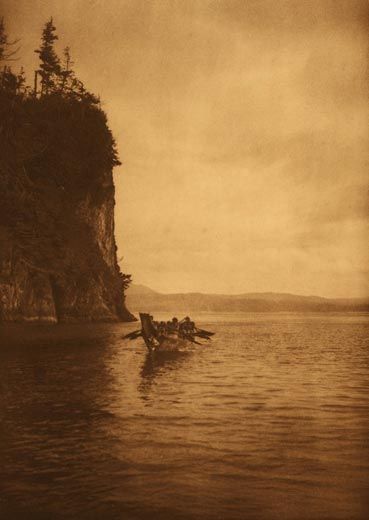

To raise money for his project, Curtis turned to Hollywood—sort of. In 1913, he traveled to the west coast of Canada to make a movie. Using members of Vancouver Island's Kwakwaka'wakw tribe (also known as the Kwakiutl) as actors and extras, Curtis documented local traditions and dances. "Pictures should be made to illustrate the period before the white man came," he wrote in 1912 to Charles Doolittle Walcott, Secretary of the Smithsonian, one of the project's sponsors. On the set, he paid Kwakwaka'wakw craftsmen to build traditional masks and costumes and even had the actors—most of whom had cut their hair European-style—wear long wigs. The film, titled In the Land of the Head Hunters, debuted in New York and Seattle in 1914 to critical success. But it was a box office failure. Audiences expected tepees and horses—not the elaborate, stylized dances and complex ceremonial masks of the Kwakwaka'wakw. "Because they weren't stereotypical Indians, people didn't know what to think of it," says Aaron Glass, an anthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Recently, Glass and collaborator Brad Evans, an English professor at Rutgers University, set out to resurrect Curtis' film. A damaged partial print surfaced in the 1970s, but it was missing key scenes. In a half-dozen archives from Los Angeles to Indiana, the pair found film reels not seen since 1915 and discovered the film's original orchestral score (filed incorrectly in a drawer at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles). Last month, the restored film was screened at Washington, D.C.'s National Gallery of Art. An orchestra of Native American musicians, co-sponsored by the National Museum of the American Indian, performed the original score.

The culture that Curtis had thought was about to disappear still thrives, preserved by the descendants of people who acted in his film almost a century ago. Many of the ceremonies that Curtis used for dramatic effect—including bits of the symbolic and highly sensationalized "Cannibal Dance" —are still performed today. Curtis' film played a vital role in that preservation. Kwakwaka'wakw cultural groups had used fragments of the movie as a sort of visual primer on how their great-great-grandparents did everything from dancing to paddling huge war canoes. "We have a group of dance performers who are all related to the original cast in one way or another," says Andrea Sanborn, director of the tribe's U'mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, British Columbia. "The culture is very much alive, and getting stronger."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)