Arresting Faces

A new book argues the case for the mugshot as art

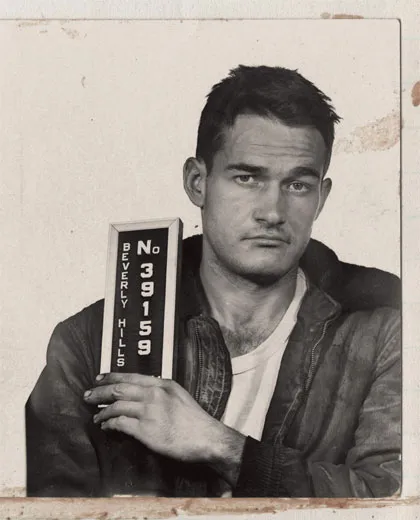

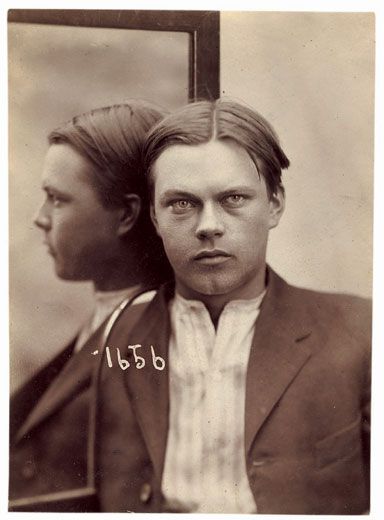

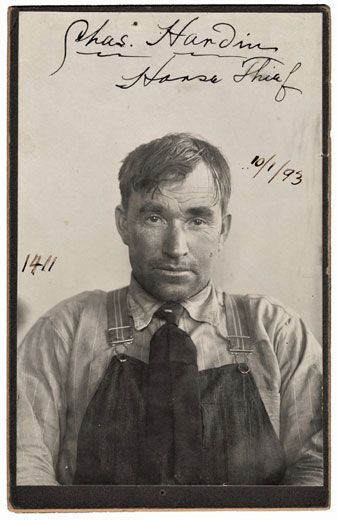

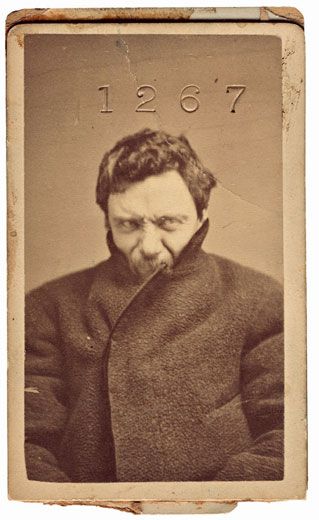

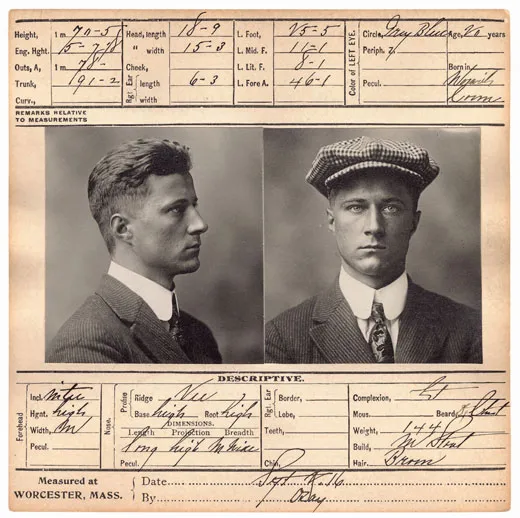

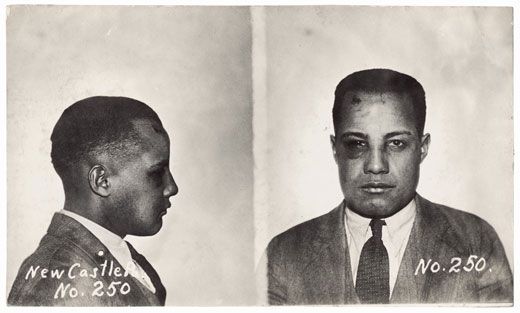

The faces are "right out of central casting," says Mark Michaelson. For a decade, the graphic designer collected old mug shots—he got them from a retired cop in Scranton, Pennsylvania, from a file cabinet bought at a Georgia auction and stuffed with pictures, and from eBay—until he had tens of thousands. All of them might have remained the personal collection of this self-described pack rat. But with the growing popularity of vernacular, or found, photographs, Michaelson's trove suddenly had wider appeal. This past fall, he exhibited the mug shots in a New York City gallery and published them in a book slicker than an L.A. loan shark.

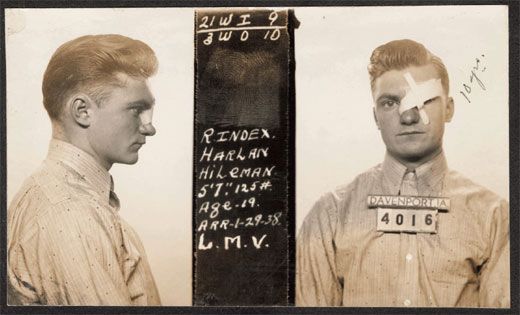

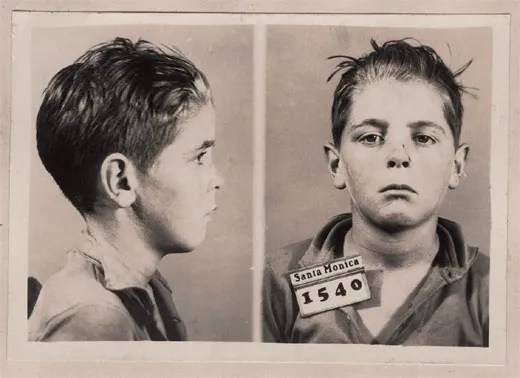

Michaelson, who has worked at Newsweek, Radar and other magazines, got interested in underworld imagery after a friend gave him a Wanted poster of Patty Hearst. For his collection, however, he avoided famous people and notorious criminals in favor of what he calls "the small-timers, the least wanted." His book is even called Least Wanted: A Century of American Mugshots. It is a sort of accidental tour of the crooked, down and out or unlucky. But because Michaelson, 51, knows little or nothing about most of the subjects, readers have to supply the backstory. "I don't have any more info than what the viewer gets," Michaelson says in a telephone interview from Berlin, where he now lives.

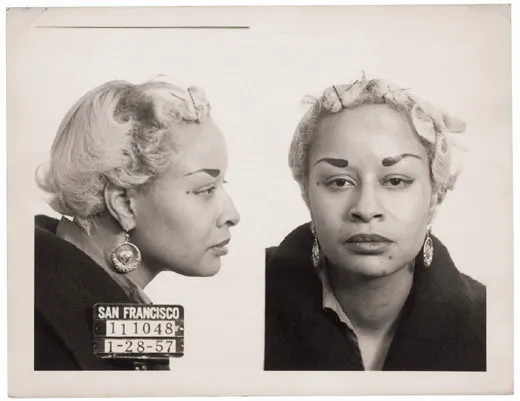

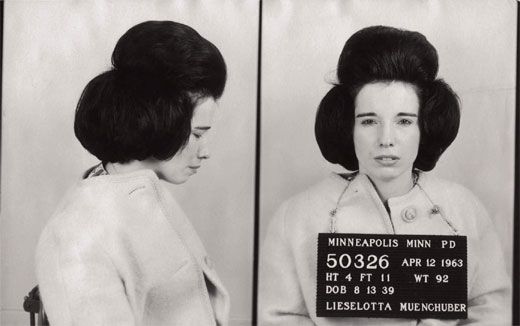

Why, exactly, were the pair of Fresno cross-dressers—clad like modest housewives—arrested on successive Tuesdays in 1963? What sort of upbringing, if that's the word, befell a Pennsylvania boy known as Mouse, who was arrested in the 1940s at ages 13, 14 and 18? We can only wonder. If the pictures are short on detail, they still add up to a vivid, impressionistic archive of American metamorphosis: bowler hats and beehives; Depression-era vagrancy and a 1970s narcotics bust; the arrival of Irish, German and Italian immigrants; the first wave of anti-Communism, in the 1930s, with the accused Communists' mugs mounted on pink cards; and the racism, as in the description of a Missouri man (a "close mouthed Negro who is probably committing burglaries"), who was arrested in 1938 for stealing "several pairs of stockings."

The New York Times called the pictures "a catalog of the human face and the things that can happen to it." But Michaelson is interested in the photographs as pop artworks, too, à la Andy Warhol. To that end, he has blown some of them up to poster size, stamped them with a number and signed his name. A gallery in Rome was scheduled to exhibit those works this past month.

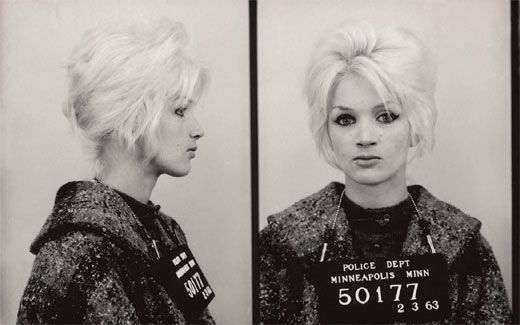

He has also posted a portion of his collection on the photo-sharing Web site Flickr.com, where people discuss and rate photographs. Responding to a shot of a thin-faced, exhausted-looking Minneapolis woman arrested in 1963, one commentator wrote, "She looks [like] a mean one, doesn't she?" Another said, "That's some serious Minnesotan crossbreeding." And another: "We can tell by her lack of make-up, oral hygiene and feminine charms that it most likely wasn't hooking." Reading the comments, one gets the feeling that Michaelson's mug shots encourage a kind of voyeurism, which doesn't always bring out the best in people.

But we are drawn to the photographs by their undeniable authenticity. In this day of flickering instantaneous images and photo-manipulation software, the mugs stare back as rare artifacts. "In an increasingly digital world," Michaelson notes in the book, "the hard copy original is an endangered species." Yet there's something else. The Least Wanted images intrigue us in the way a collection of old passport photos might not. A mug shot captures people at their lowest or most vulnerable. We look hard at their faces, calculating guilt or innocence. And then look harder.