Artist Kumi Yamashita Creates an Amazing Human Figure Out of Shadow

Coming soon to the National Portrait Gallery, an old art form gets reinvented

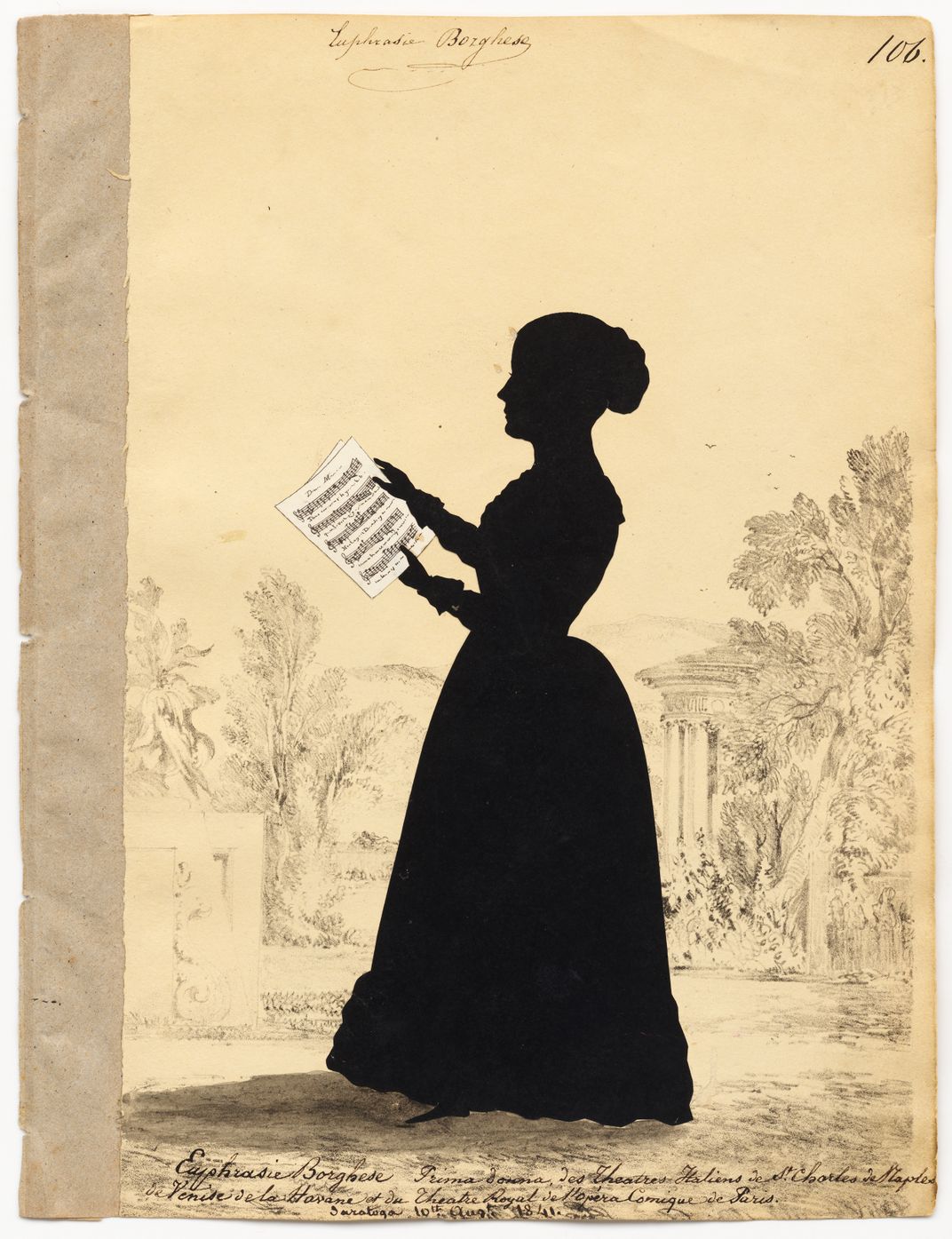

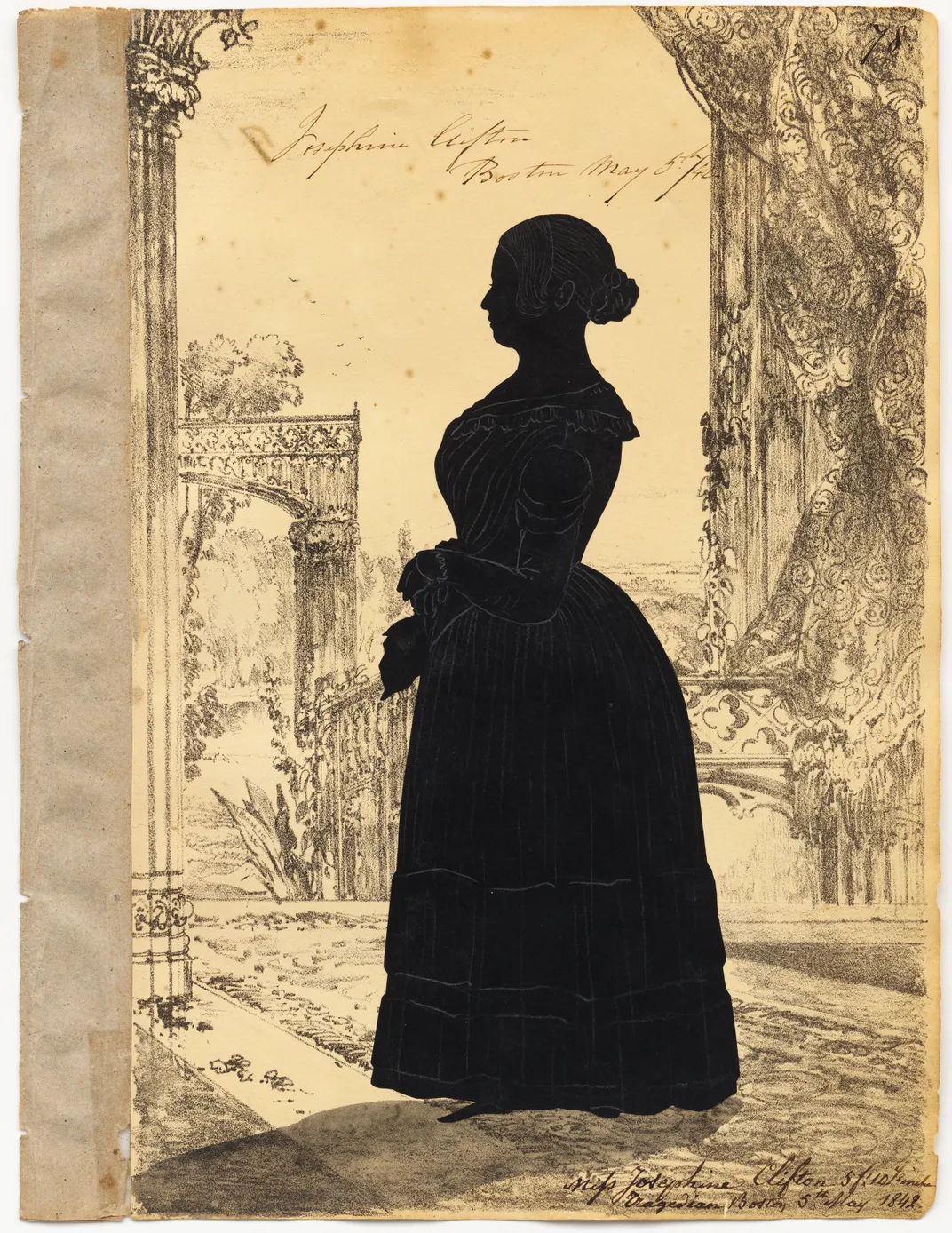

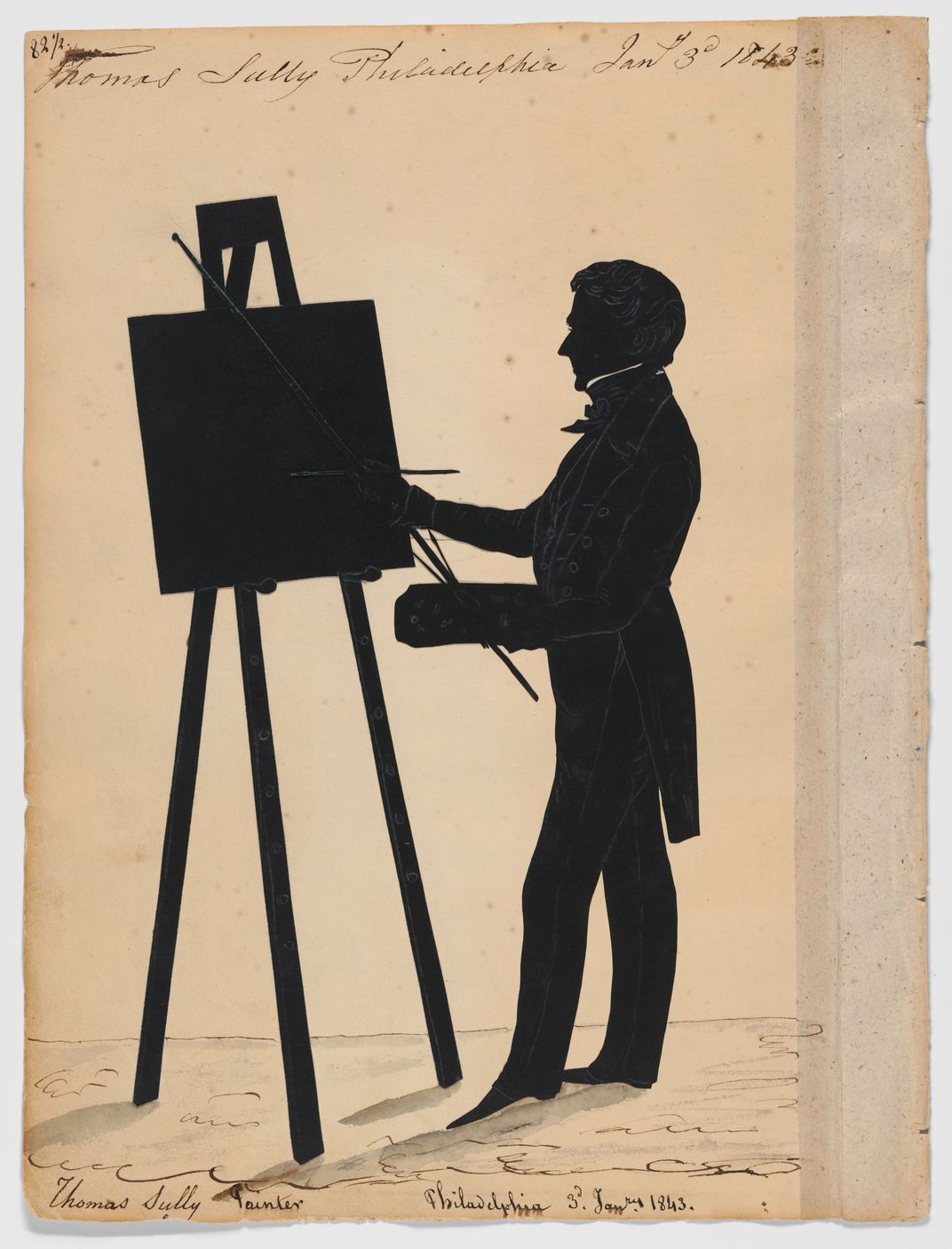

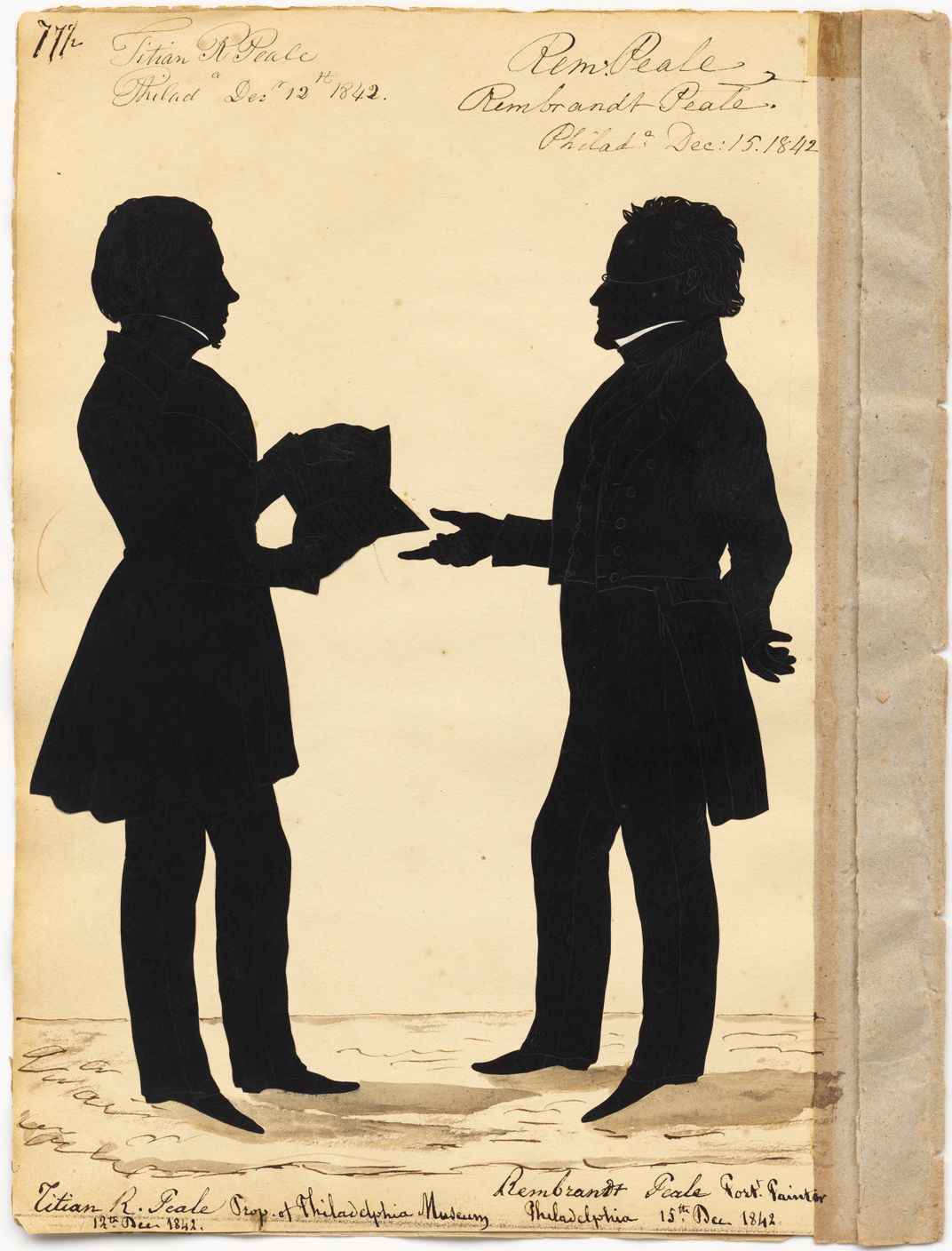

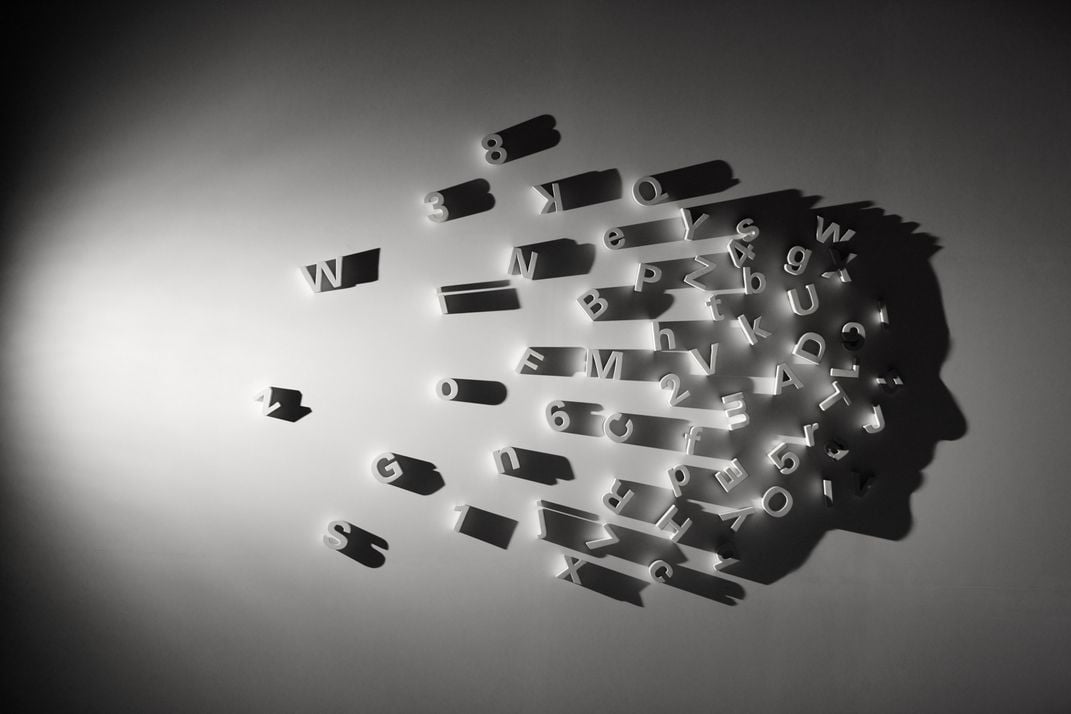

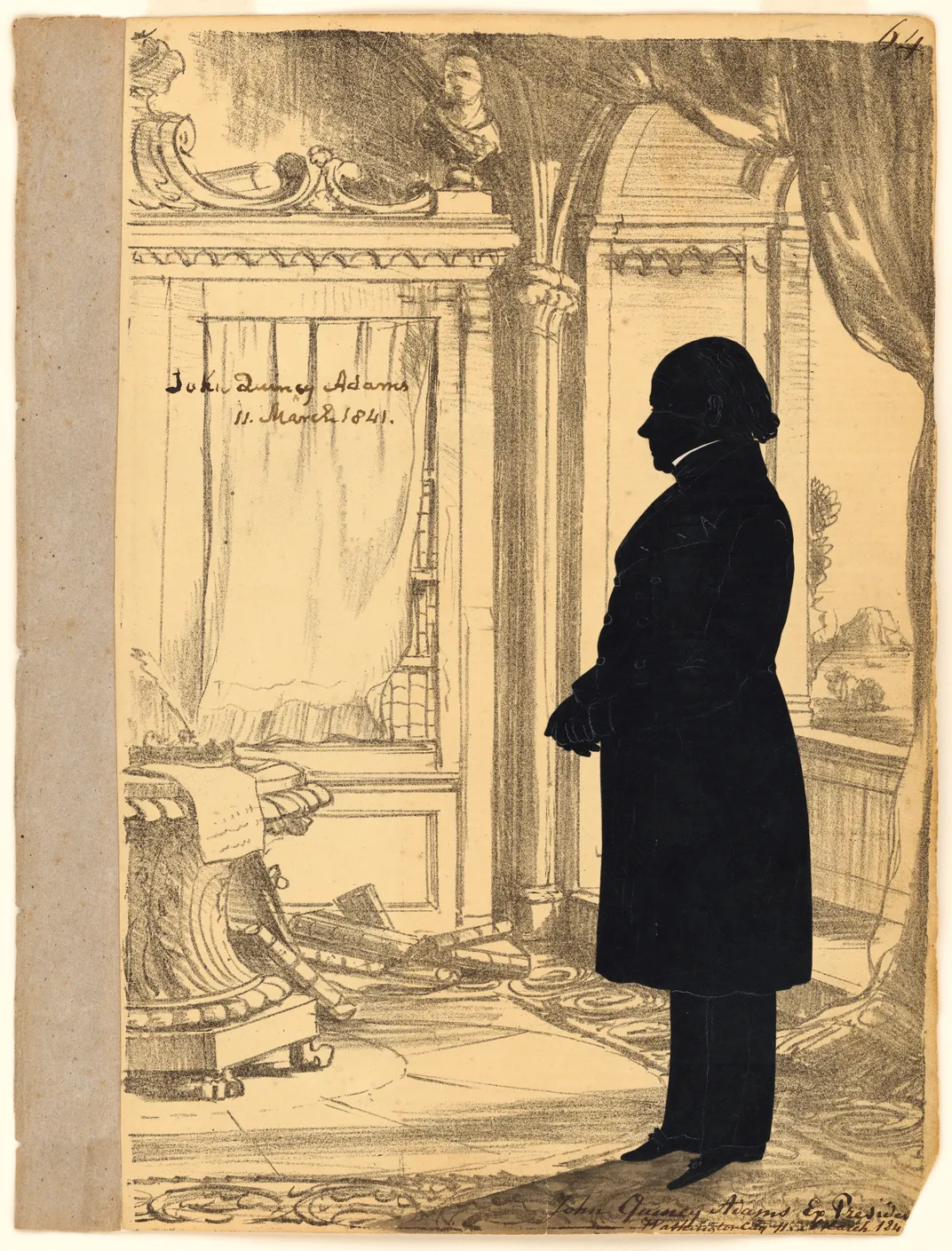

In the early 19th century, artisans created silhouettes of Americans of every social stratum, from enslaved people to presidents. These profiles, often cut from black cardstock and pasted against a contrasting background, could be made in minutes and duplicated easily for sharing. They represented “the democratization of portraiture” before photography took hold, says Asma Naeem, curator of a new exhibition of historical and contemporary silhouettes opening in May at the National Portrait Gallery. Three pieces are by Kumi Yamashita, who spent six months sketching and carving her wooden Chair (2015) so that a single light placed in exactly the right spot would create the shadow of a young woman sitting on the chair. The Japanese-born, New York-based artist has long worked with shadows, which “impart subtle qualities,” she says, and “reveal this extraordinary dimension where we see no borders, no races, no separation...only the essence of what we are.”

Silhouette: The Art of the Shadow

Elegant and enigmatic, the silhouette is the simplest of art forms—but that simplicity belies a rich and varied past. In this first major work on the art of the silhouette, art historian Emma Rutherford draws from dozens of American and European sources to create a fascinating history of the art form.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)