This Artist Redefines a “Chiseled Body”

Life-size and hyper-detailed, these anatomical mosaics draw on ancient inspiration

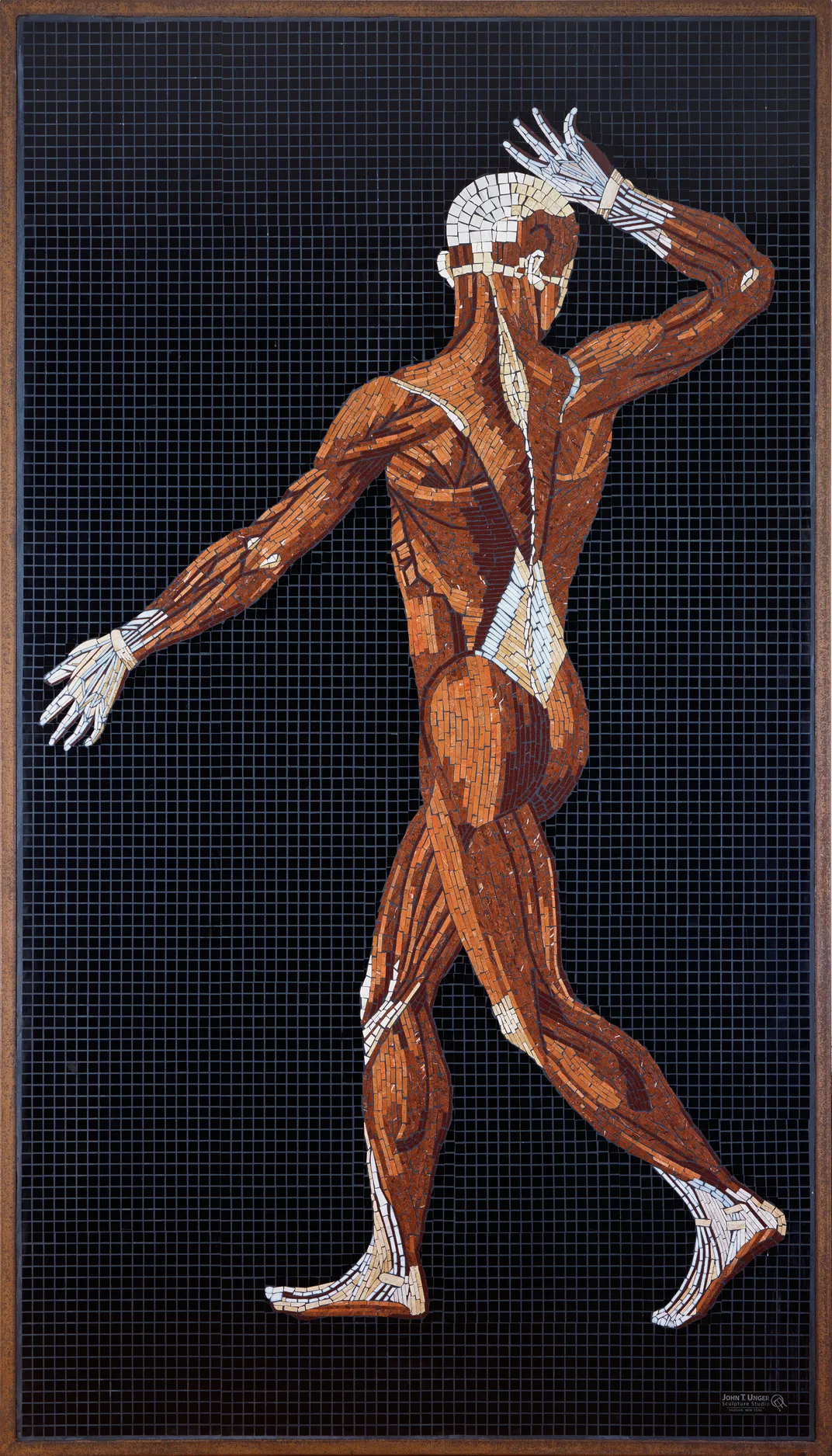

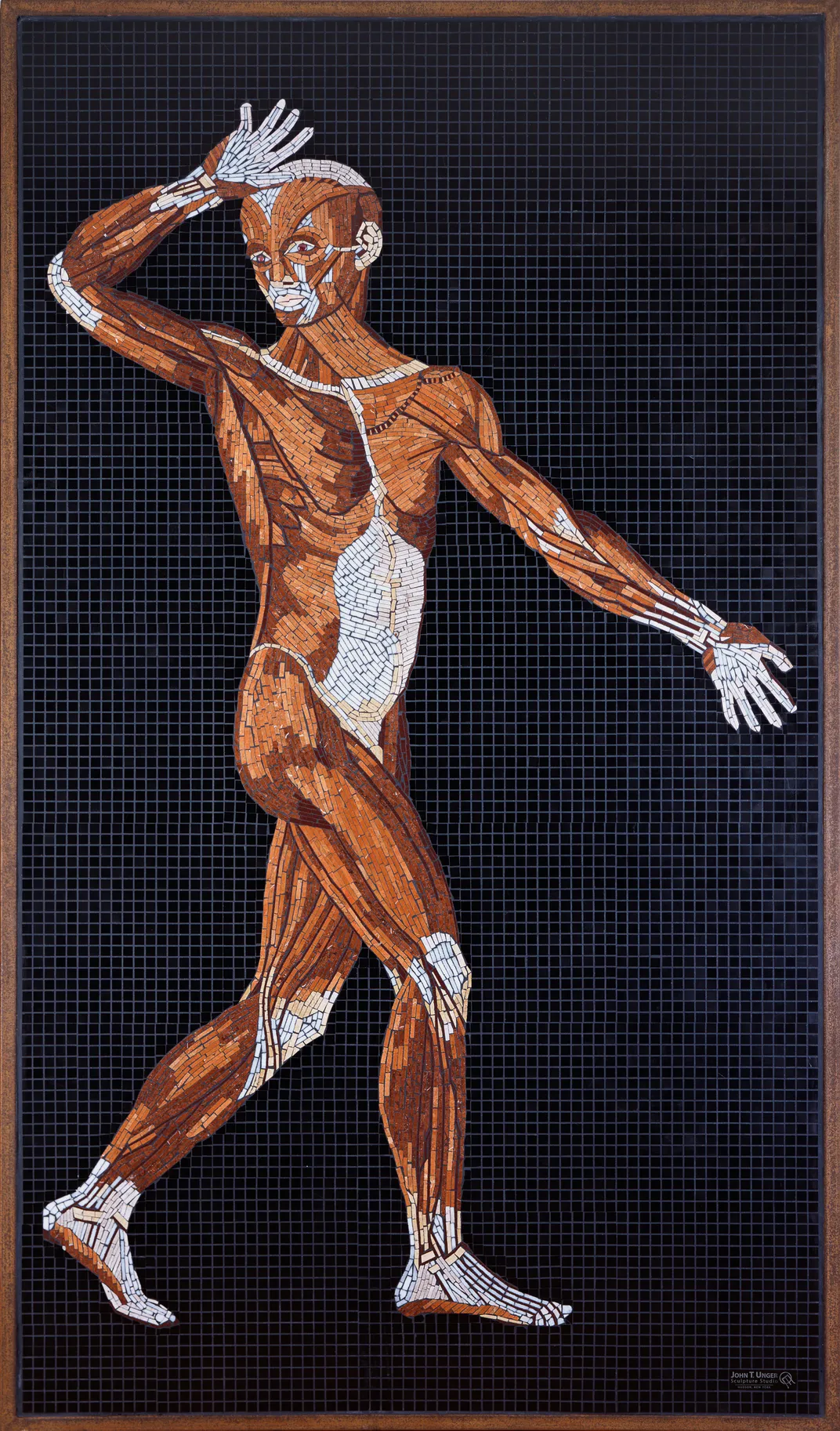

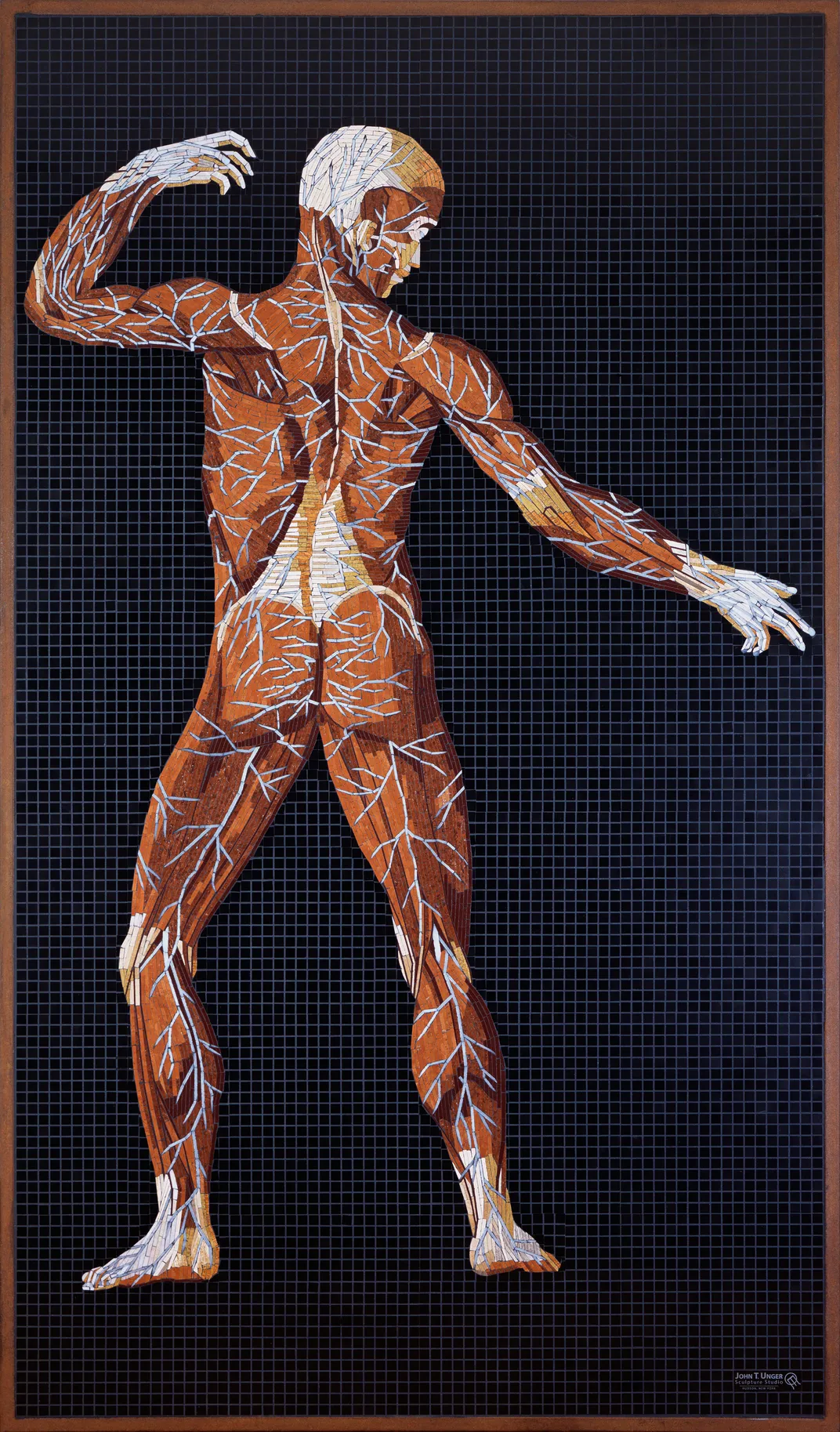

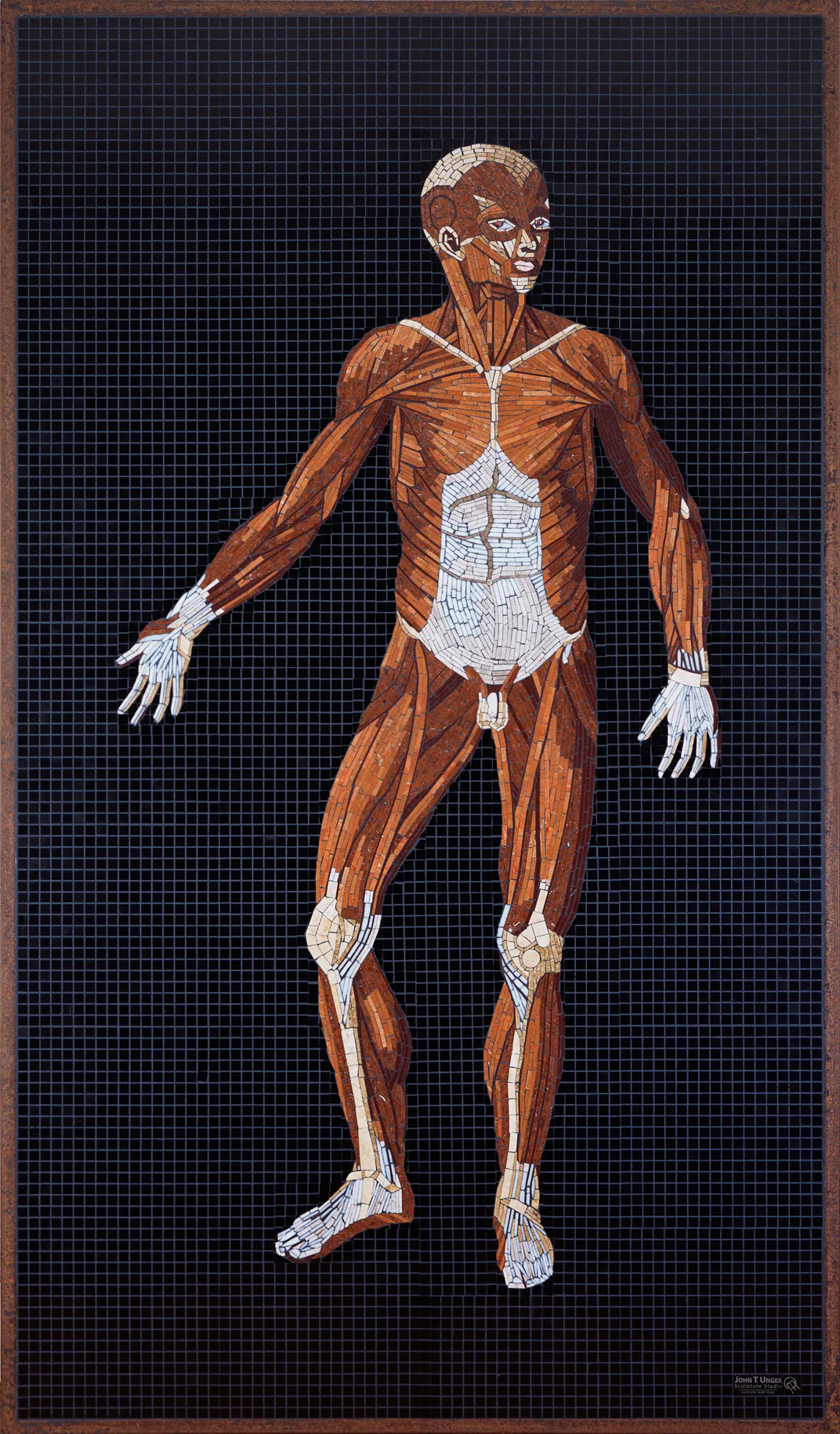

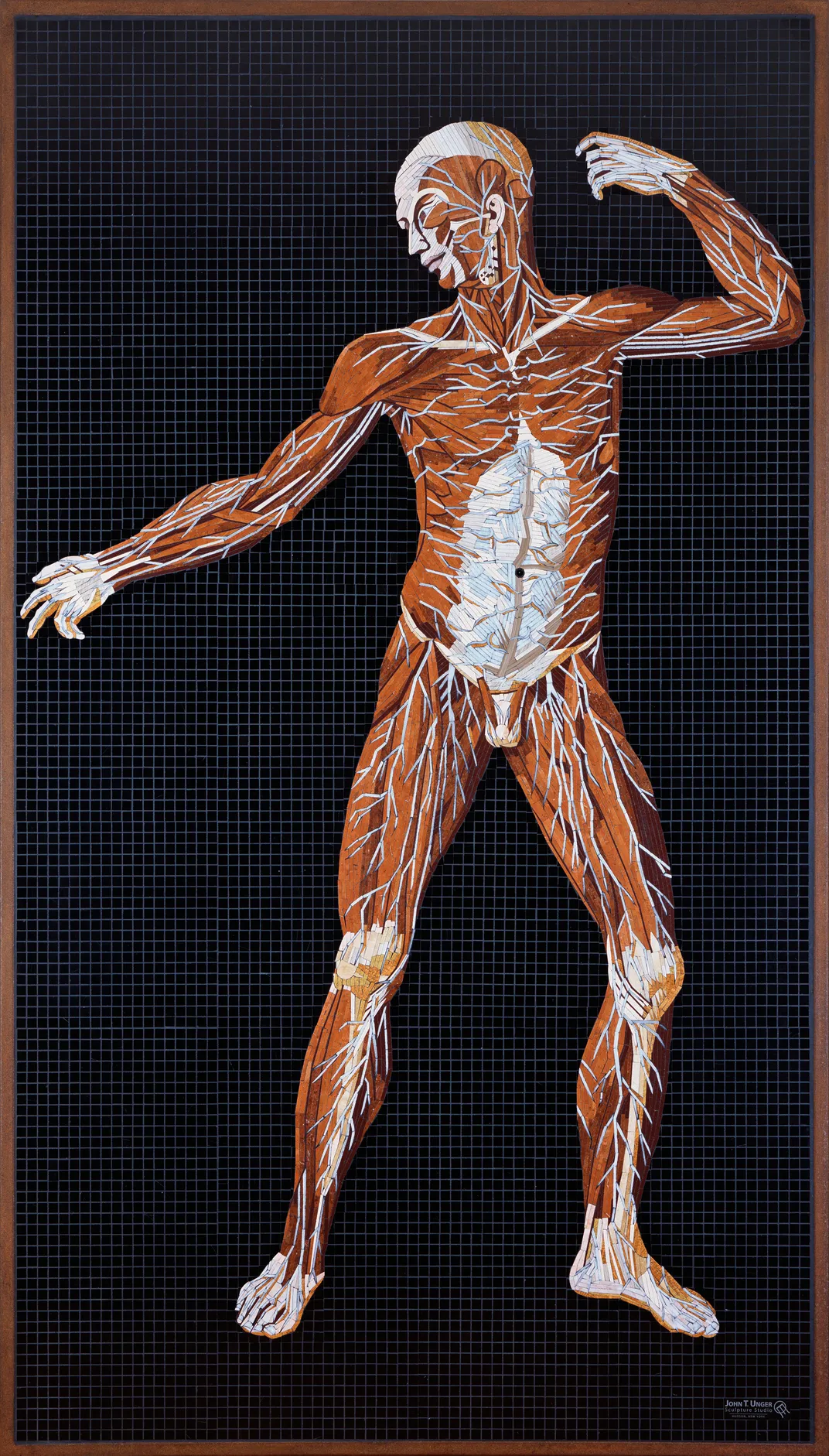

When artist John T. Unger began work on a mosaic depicting the muscular system for a physical therapist’s office more than ten years ago, he had an epiphany: marble and stone exist in all the same colors as the interior of the human body.

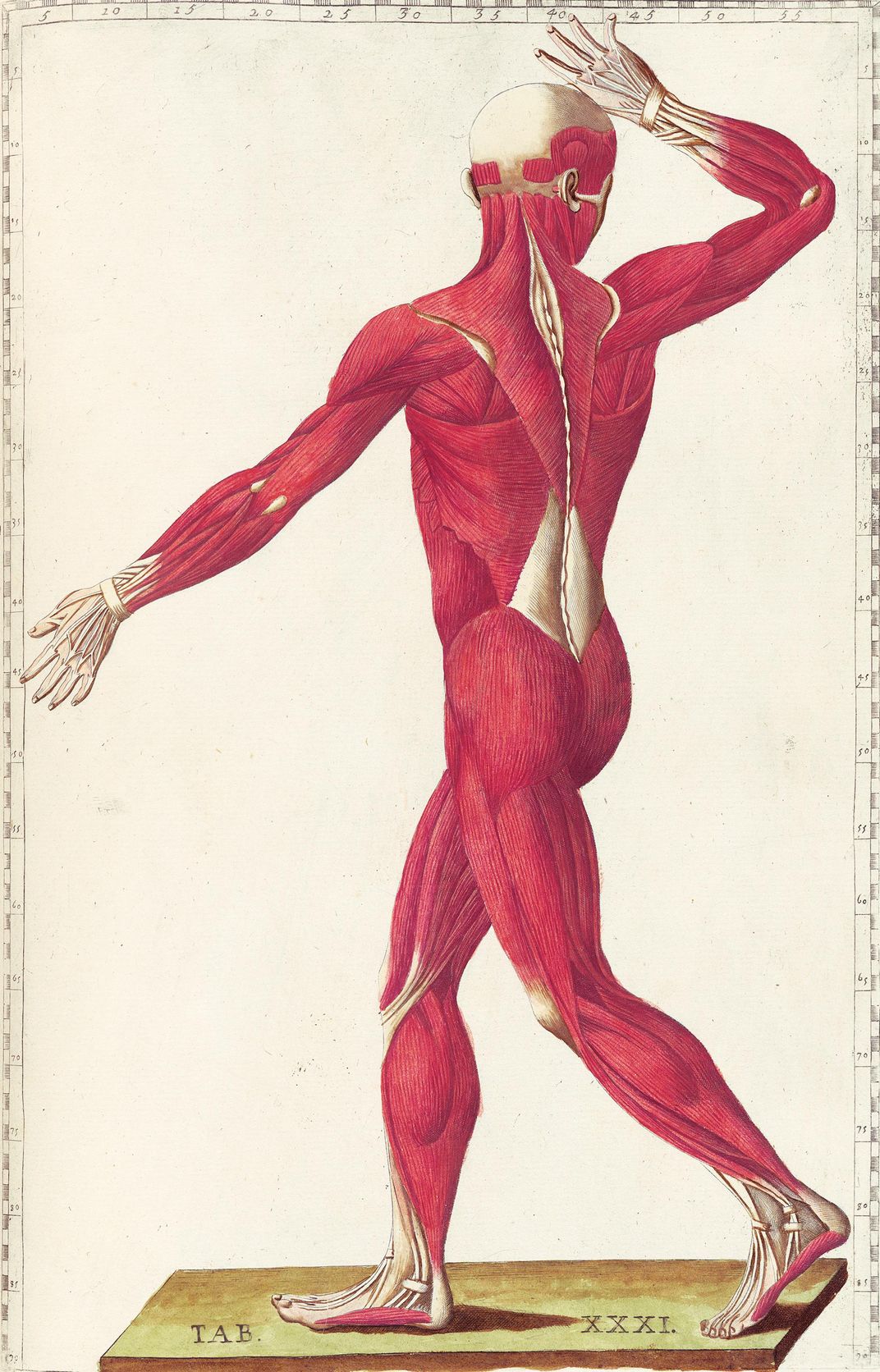

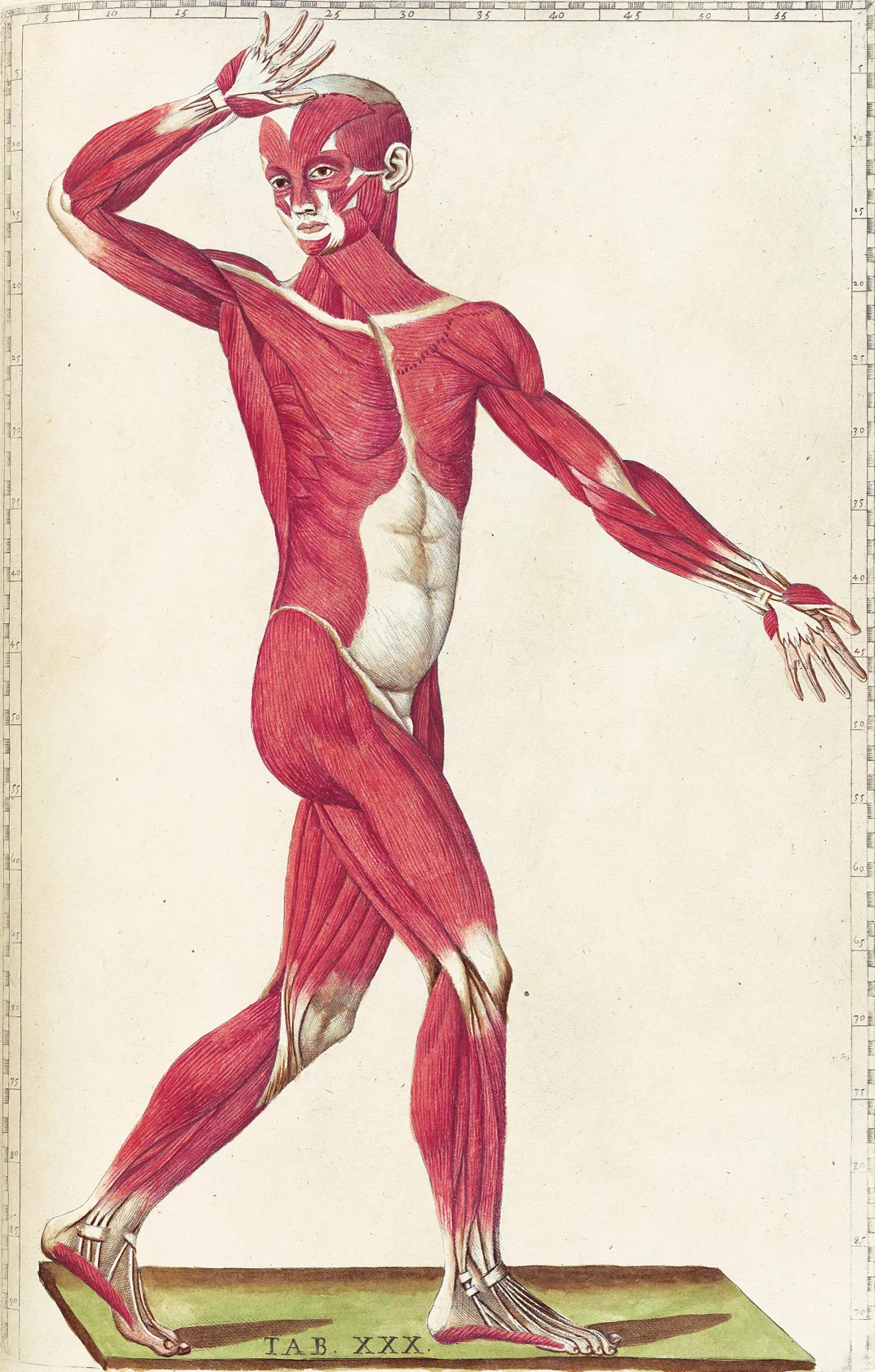

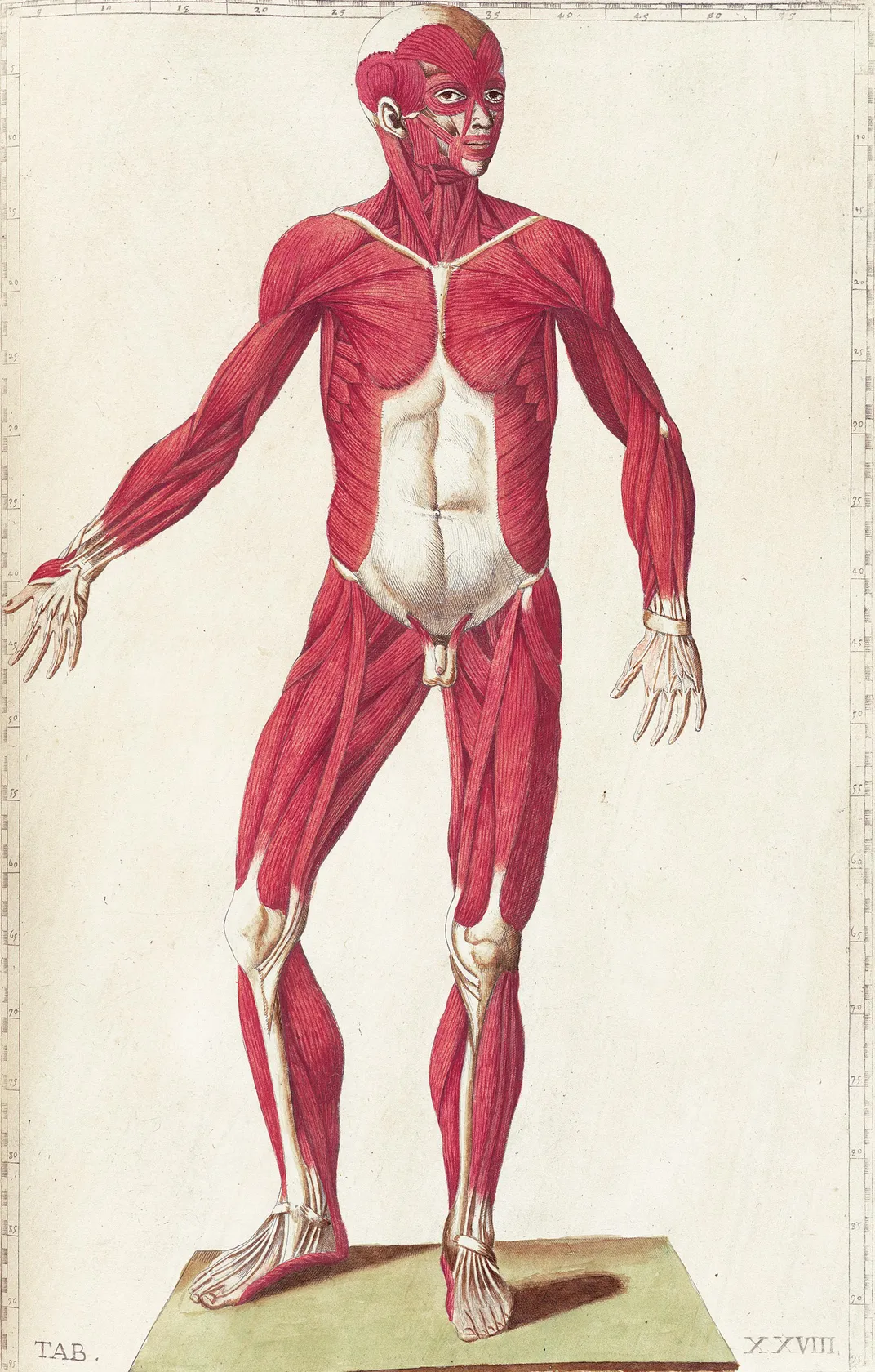

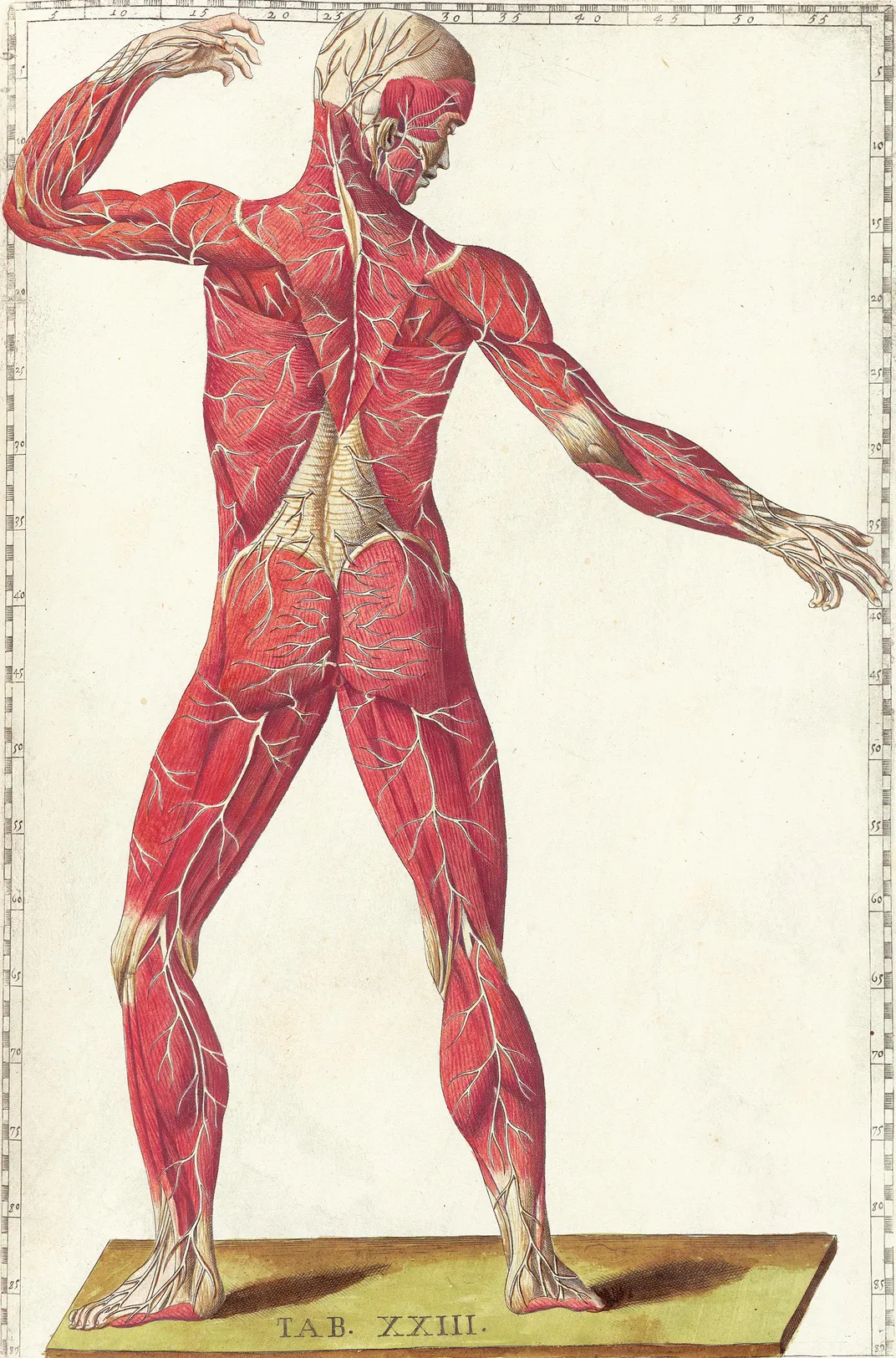

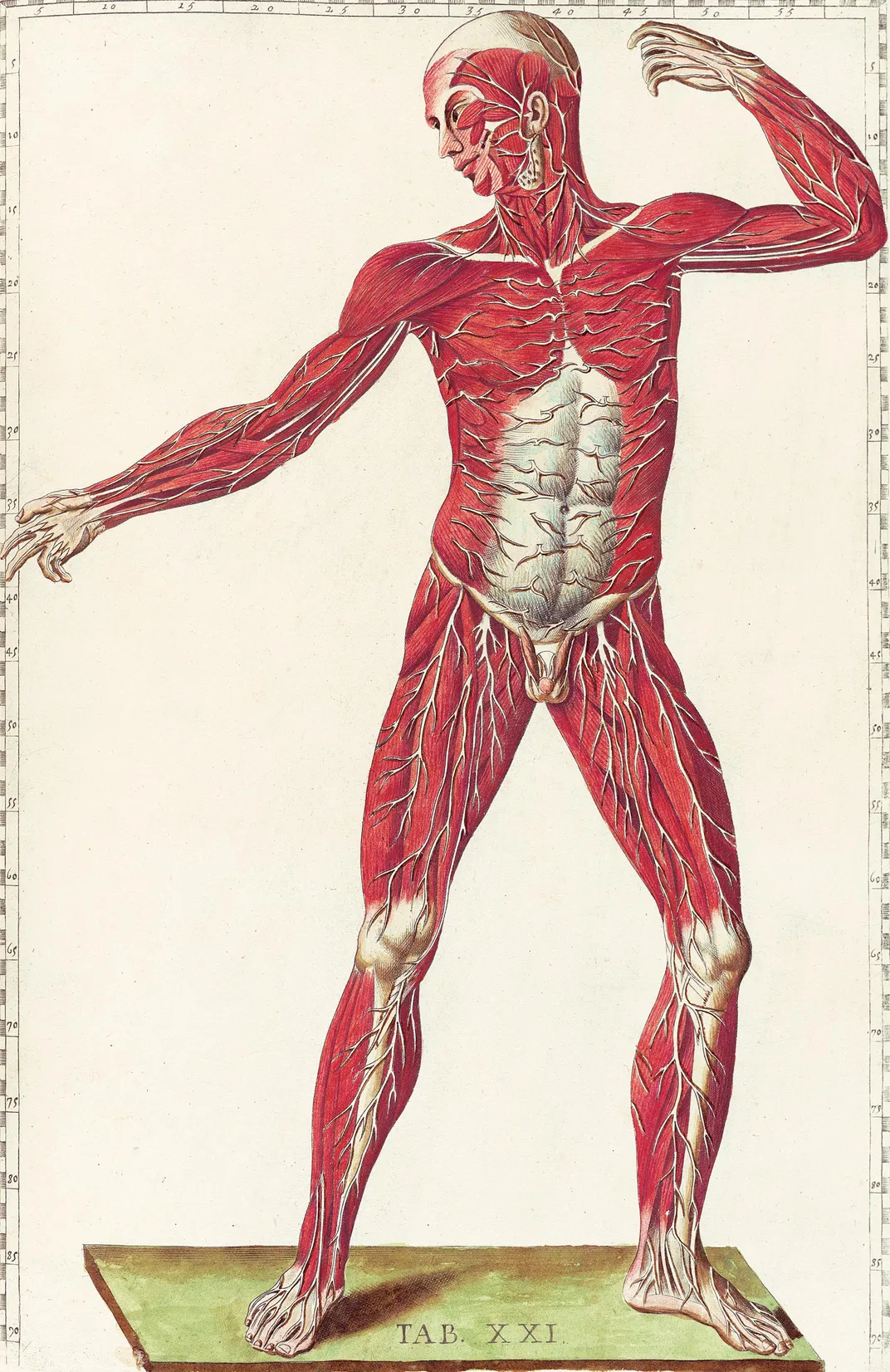

Though the mosaic ultimately ended up in Unger’s studio in Hudson, New York, the idea of bodies etched from stone haunted him. He dove into exhaustive research to learn whether it might even be possible to create highly detailed, accurate anatomies through mosaic. That led him to the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s website, where he found images that were just the inspiration he sought: a series of anatomical engravings by 16th-century Italian physician Bartholomeo Eustachi.

Printed, bound and individually painted from copper plates etched by hand, Unger says the intrinsically artistic nature of the original works also drew his interest. In 2015, he embarked on a project to recreate 14 of Eustachi’s drawings in life-size mosaics, each 7 by 4 feet in dimension.

“I chose Eustachi’s drawings because of their beauty, and because every stage of his original drawings was done a little bit at a time, by hand, with relatively primitive tools,” Unger says. “And the fact that these drawings are still relevant after 465 years feels like they deserve to be immortalized.”

You may not walk away knowing the Latin names of each bone, ligament and muscle of Eustachi and Unger’s creations (Eustachi’s work famously lacks text descriptions). But Unger believes viewers can still gain a better understanding of the way the human body is built, and how it functions as a system through his mosaics and Eustachi’s engravings—the goal of any modern anatomical text or digital software.

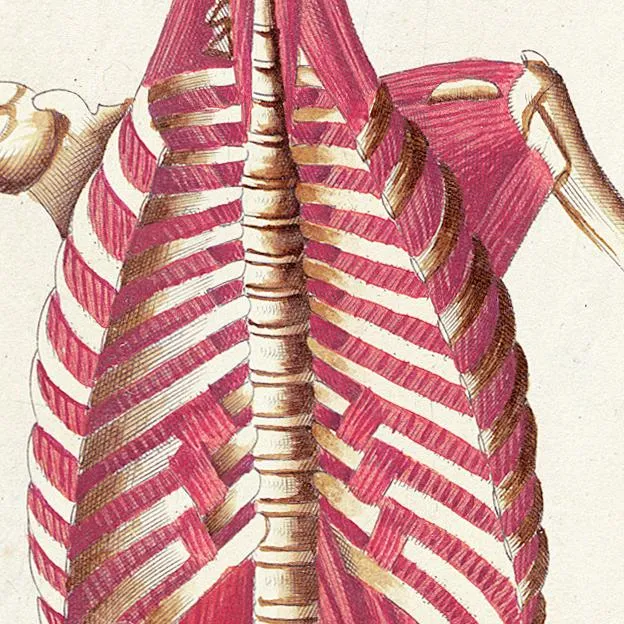

Unger selects from a blend of stones to match Eustachi’s drawings as closely as he’s able. Rust-red marble stands in for the magenta of the muscle tissues, pink quartz for dusky lips, pale travertine for the skeletal system and fascia. For later mosaics that involve the vascular system, Unger plans to use brilliant lapis lazuli for veins and red jasper for arteries. In the five mosaics he’s completed so far, the figures’ eyes are set in star rubies and sapphires.

“I enjoy imagining the mosaics as fossils with extremely well preserved soft tissue,” Unger adds.

Laura Schichtel, a Michigan-based artist who knew Unger when he also lived there, gifted him the first four star sapphires for his initial mosaics.

“He was posting about wanting to use gems for the eyes of his mosaics, and I had them—I was gifted the stones, and as a jeweler I didn't think I would use them. They were perfect for paying it forward,” Schichtel says. “John is a rare bird in that he continues to push himself within a medium he worked in. These mosaics are many years in the making, and a testament to his tenacity as an artist.”

Debating the Body

If “Eustachi” rings a bell, it’s because we have a body part that bears his name: the Eustachian tube, which he discovered and described. (It’s the tube between your middle ear and nasal cavity that lets you “pop” your ears.)

Though obscure today, in his era, Eustachi was an important contributor to new knowledge of the structure and function of the human body. Along with the Eustachian tube, he’s also credited with the first accurate description of the ear’s complicated cochlea, as well as the discovery of the adrenal glands.

Eustachi’s body of work also added to a hot debate that raged in the medical field in the mid-1500s: whether the very foundations of human anatomy were as accurate as everyone believed. Virtually all accepted knowledge of anatomy at the time hinged on the work of one outsized figure: Galen, a 2nd century Greek physician and surgeon, whose comprehensive treatises on human anatomy and physiology were considered incontestable.

“Before the middle of the 16th century, there were no anatomically accurate texts available for study in the Western world,” says Stephen Greenberg, head of rare books and early manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine. “Galen is the big name, but his works were not illustrated. Eustachi is one of these people who start reexamining everything, and he’s one who realized that what people thought was gospel was actually Galen lying.”

As in medieval Europe, human dissection had been prohibited in ancient Rome. But by breaking with that practice, Eustachi and others, including the prominent Belgian physician Vesalius, revealed that Galen had made numerous inaccurate claims—primarily by assuming that his primate animal subjects were identical to humans.

Eustachi’s first work, Opuscula anatomica, which featured only eight of his engravings, was published in 1564. Then, 130 years after his death, an additional 38 plates were discovered and assembled into the Tabulae anatomicae, and published in 1714.

Flesh in Stone

Unger was drawn to the Tabulae images over Vesalius’s more enduring and accurate black-and-white works mainly because of the vibrant colors used to bring Eustachi’s engravings to life.

As to his choice of material, Unger says he relishes the challenge of cajoling soft shapes from rigid minerals, mimicking the organic tissues and bone in an inorganic material.

To achieve the long, lithe lines of the muscles and curving shapes of the bones, Unger quickly realized he couldn’t use the small pre-cut squares typical of many mosaic creations. He carefully shapes each piece of the mosaic with multiple tools—nippers, saws, grinders and polishers—to achieve the proper dimensions. Some pieces are as thin as a millimeter across, but altogether each mosaic weighs from 300 to 350 pounds.

One glaring omission that Unger says can’t be helped is the lack of female figures. Working strictly from original source material, he notes that he’d prefer to make the series more diverse, but that female anatomical representations from that time are sorely lacking.

Though he’s working on finishing up the sixth piece, Unger hopes that once the mosaics are done and all together on display, the effect will be a spectacle. He hopes to mount them on a traveling exhibition once the set is complete, which he estimates will take another two to three years.

“It just blows my mind that I can make an image out of stone that’s that realistic looking,” Unger says. “What I hope people take away from it is something you spend time with, and really look at the levels of detail, and get lost in it.”

“In terms of an artistic endeavor, it’s seriously cool,” Greenberg adds. “As a scientist, no one will learn anatomy from the mosaics. But for someone who finds the structure of the human body to be aesthetically interesting, it’s super cool.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)