Auctioning a Beloved Thomas Hart Benton Collection

Perhaps the nation’s best collection of Benton prints was assembled by an idiosyncratic Texan named Creekmore Fath

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111107073006Thomas-Hart-Benton-Going-West-lithograph-1934-web.jpg)

I felt a tinge of sorrow when I learned that the collection of books and prints owned by the late Creekmore Fath would be going up for sale at the auctioneer Doyle New York on November 8. But the sale provides an occasion to write a brief tribute to a truly memorable American character, and one of the most important collectors of the great American artist Thomas Hart Benton.

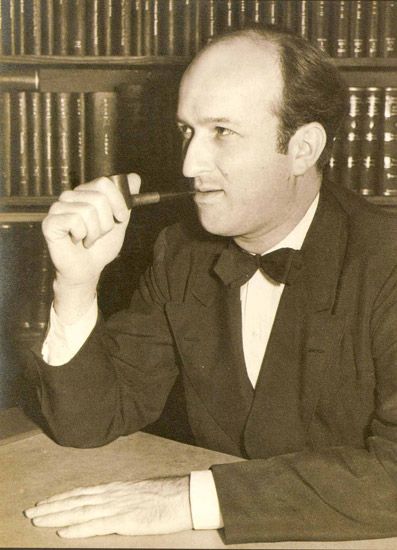

I first met Creekmore in Kansas City back in the mid 80s, when I had just started doing research on Benton. He was a distinguished, courtly man whom I never saw without a bow tie; he was also the product of rural Texas, who spent much of his life in the rough-and-tumble of state politics. Though fascinated by gentility and eager to join the ranks of the elite, he was also the champion of the poor and dispossessed and an early, ardent champion of civil rights. Like America itself, his personality was the synthesis of different constituencies, some of them in harmony, others discretely at odds with each other.

The bewilderingly different sides of Creekmore’s personality were expressed by the house’s long tunnel of a library, filled with books that mirrored his various enthusiasms, including American political history, the Bloomsbury group and its offshoots (he had a notable collection of letters from D. H. Lawrence), and American literature (he had innumerable first editions, many of them signed, by writers ranging from Sinclair Lewis to Henry Miller).

Surely the highlight was the collection of Benton prints—the most complete in private hands. Benton was the unapologetic artist of the American heartland, a figure who, like Creekmore himself, bridged traditional boundaries. Creekmore’s collection will be dispersed, but his catalogue raisonne of Benton’s prints remains one of the most remarkable books in the American field.

Born in Oklahoma, Creekmore Fath grew up in Cisco and Fort Worth, Texas, and in 1931 his family moved to Austin, so he could attend the university there. After getting a law degree, Creekmore practiced law in Austin for about a year, then went to Washington as acting counsel to a congressional subcommittee investigating the plight of migrant farm workers. He went on to serve in a variety of legal posts in Washington, including a stint with Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House, and he returned to Texas in 1947 after marrying Adele Hay, the granddaughter of McKinley’s Secretary of State, John Hay.

Creekmore ran for Congress, campaigning in a car with a canoe on top, which carried the slogan: “He paddles his own canoe.” As an FDR liberal democrat in a conservative state, he was paddling upstream, and was soundly defeated. He helped Lyndon Johnson win the 1948 Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate by defeating former Texas Governor Coke Stevenson, by 87 votes. During McGovern’s failed presidential run in 1972, Creekmore became friendly with an eager young organizer in his twenties, Bill Clinton; and years later, on the occasion of Creekmore’s 80th birthday, he was rewarded with a sleepover in the Lincoln bedroom of the White House. He died in 2009 at age 93.

For some reason, Creekmore was a born collector. Book and art collecting were part of his being. As he once wrote: “The desire to collect, and the pleasure derived from each acquisition, are as exciting and compelling as passionate love.” He got started early. As he once recalled:

My first venture at collecting art took place at the age of twelve, as the result of an advertisement in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. For the sum of one dollar I acquired ‘genuine reproductions’ of three of Rembrandt’s greatest etchings: Dr. Faustus, The Three Trees, and The Mill. I still have them.

His Benton collection got its start in 1935 when he clipped a New York Times advertisement for Associated American Artists (AAA), which was offering prints by living American artists for five dollars each. Four years later, he ordered a print from AAA—Benton’s I Got a Gal on Sourwood Mountain—purchasing it with part of the fee that he received from the first law case that he tried.

The collection grew, particularly during the 1960s, when he was working as counsel to a Senate Committee chaired by Ralph Yarborough, whom he had helped elect. During this period he was often in New York and had many opportunities to purchase prints from the Weyhe bookstore, the Sylvan Cole Gallery and other sources. When he wrote to the New Britain Museum in New Britain, Connecticut, which was said to have a complete collection, he found that he had several which they did not know about. Before long he realized that he was compiling a catalogue raisonne—a complete listing of Benton’s prints. And this led him into correspondence with the artist himself.

Creekmore had a bit of bluster and definite sense of his own importance. But what’s remarkable about his catalogue raisonne of Benton’s prints is its modesty. Much art history is about the art historian rather than the art—almost as if the art historian were standing in front of the work of art, blocking the spectator’s view. Creekmore had the genius to step aside and let the artist speak for himself. His vision of the shape the book could take flashed into his mind during his very first exchange of letters with Benton, in January of 1965, when the artist wrote:

P. S. I assume you are a Texan. It might interest you to know that I am half Texan myself. My mother came from Waxahachie and I knew the country thereabouts quite well as a boy. My grandfather had a cotton farm a few miles from town. The lithograph Fire in the Barnyard represents an incident which occurred on an adjoining farm when I was around ten or eleven years old.

It occurred to Creekmore that Benton’s comments about his prints might be valuable. Indeed, the final catalogue has a brief listing of each print, its date, how many impressions were printed and perhaps a few additional comments, followed by a space in which he provided Benton’s remarks about each subject—in Benton’s handwriting. (Benton’s letters to Creekmore will be included in the Doyle sale.) Since Benton made prints that record the compositions of most of his major paintings, the result is one of the best records anywhere of Benton’s achievement. When I wrote a biography of Benton back in the 1980s I referred to it constantly; along with Benton’s autobiography, An Artist in America, it was my single most valuable printed source.

Creekmore’s collection of Benton was missing only four early prints, which exist in just one or two proofs. When I last spoke to Creekmore, he indicated that he was planning to donate his collection to the University of Texas at Austin. but for whatever reason this never occurred. It’s a shame in a way since there are surprisingly few large gatherings of Benton prints in public collections: those at New Britain, and those at the State Historical Society in Columbia, Missouri are the only two I can think of that come close to being comprehensive. But perhaps it’s also fitting that a passionate collector should disperse his holdings so that they can be acquired by other devoted art-lovers like himself.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)