Beacon of Light

Groundbreaking art shines at the extraordinary new Dia: Beacon museum on New York’s Hudson River

It’s only fitting that the most eagerly awaited museum in the world of contemporary art is more than an hour removed from New York City’s frenetic art scene. Many of the artists whose works went on permanent display this past May at Dia:Beacon, as the new museum is called, put space between themselves and an art world they saw as compromised and overly commercial. “These artists were inspired more by the American landscape and the American spirit than by the SoHo art scene,” says collector Leonard Riggio, chairman of the Dia Art Foundation, which created the museum. “The idea of being an hour-plus away from New York City is more important than being close to it.”

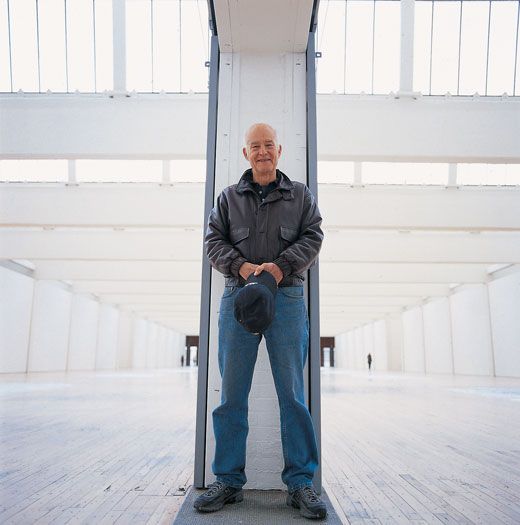

Dia:Beacon has 240,000 square feet of exhibition space, which is more than that of New York City’s Guggenheim, Whitney and Museum of Modern Art combined. It exhibits a concentration of monumental works (many seldom, if ever, seen in public) by land artists, minimalist artists, conceptual artists and installation artists. At Dia:Beacon, says artist Robert Irwin, who helped transform the 1929 Nabisco box- printing factory in Beacon, New York, into a radiant showcase for art, “the viewer is responsible for setting in motion his own meaning.”

Most of the outsize works on view in Dia:Beacon’s immense skylit galleries fill a room or more. John Chamberlain’s sculpture Privet, for instance, is a 62-foot-long, 13-foot-high hedge fashioned out of scraps of chrome and painted steel. And Walter De Maria’s Equal Area Series (12 pairs of flattened, stainless-steel circles and squares that lie on the floor like giant washers for some enormous machine) extends through two galleries totaling 22,000 square feet.Most of these works cannot be seen in their entirety from any one place; you must walk in, around, and in some cases, within them, as in a landscape. “Difficult” art becomes accessible, the thinking goes, when a viewer’s response is visceral. And concentrated.

“What makes this museum very special is its focus on a relatively small number of artists who are shown in great depth in circumstances as close to perfect as any space I have seen,” says James N. Wood, director and president of the Art Institute of Chicago. “It’s totally committed to giving an art that is not necessarily ingratiating an environment where it has the best chance to speak in its own right.”

Many of the 20 or so artists represented at Beacon—a hugely influential group that includes Louise Bourgeois, Dan Flavin, Walter DeMaria, Michael Heizer, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, Richard Serra and Andy Warhol—began their careers intent on challenging some basic assumptions about art. Why did a sculpture have to sit on a pedestal and occupy space? Why did a painting have to be something you stood in front of and looked at? Why did it have to stop at the edges? Did art have to be an object at all?

Without a viewer’s response, they felt, their art was incomplete. “Things work in relationships. Everything is interactive,” says Dia artist Robert Irwin, who began in the 1950s as an abstract painter and who, along with Dia Art Foundation director Michael Govan, was responsible for creating a master plan for the renovation of the factory and the design of outdoor spaces. He says he approached Dia:Beacon as an artist rather than an architect. Instead of using a drawing board or models, he conceived his plan, which is itself listed as one of the artworks in the Dia collection, by walking around, back and forth, inside and outside the complex. He thought of the museum as a “sequence of events, of images,” and he was mindful of the order in which visitors would enter and progress through its spaces.

At Dia:Beacon’s entrance, Irwin planted hawthorn trees, which bloom white in spring and are heavy with red and orange berries in winter. They will grow to 25 feet, roughly the height of the four flat-roofed connected buildings—including a train shed—that once housed the plant.

One of the few things Irwin added to the existing structure is a small, low, brick-lined entrance. Pass through it, and “boom!” says Irwin, the ceilings soar and light floods through north-facing, sawtooth skylights and boomerangs off maple floors. You can see down the length of the twin galleries ahead, 300 feet, to industrialsize sliding doors. Through those open doors other galleries stretch another 200 feet toward sun-blasted, south-facing windows. “That moment of entering is really the power of the building,” says Irwin.

The vast space swallowed up the 4,500 visitors who thronged to it opening day. In its first six weeks, 33,000 people visited the museum. “People ask me what makes this place different,” says Dia director Michael Govan, 40. “There are very few places with concentrations of works, even by these artists, that are so all-encompassing and environmental. The buildings, in a way, are big enough to allow all of the artists to have their own world and the visitor to have that fantastic experience of going from world to world.”

Michael Heizer’s 142-foot-long sculpture, North, East, South, West, for instance, steals the show for many visitors and most dramatically illustrates the idea of the interaction between the viewer and the art. The work, which Heizer calls a “negative sculpture,” consists of four massive, geometric forms sunk 20 feet into the floor of the gallery. Standing at the edge of these excavations, you may experience a hint of vertigo, even as your fear of falling competes with an impulse to throw yourself in.

Andy Warhol is represented with 72 of his Shadows paintings, a series of 102 renderings of the same difficult-to-decipher shadow in a corner of Warhol’s studio. Designed to be hung together edge to edge, like a mural, each grainy silkscreen is treated differently—printed on a black or metallic background and washed in a spectrum of vaporous colors, from Day-Glo green to choirboy red. Warhol produced the series in less than two months, between December 1978 and January 1979, showed parts of it in an art gallery, then used it as a backdrop for a fashion shoot for the April 1979 issue of his magazine, Interview.

Beyond the Warhols, the world that the German-born artist Hanne Darboven has constructed—called Kulturgeschichte (Cultural History), 1880-1983, consists of 1,590 framed photographs, magazine covers, newspaper clippings, notes, personal papers and quotations, all hung floor to ceiling in a grand, overwhelming onslaught of information. The effect is not unlike walking through a history book.

At the southern end of the museum, a rarely seen work by the late artist Fred Sandback re-creates part of his 1977 Vertical Constructions series. Sandback used colored yarn to outline an enormous upright rectangle. There’s another one just like it a few feet away. The space they diagram appears as real as a wall of glass. You seem to be on the outside looking in, but if you step over the yarn to the other side, you find yourself once again on the outside of the illusion.

Beyond Sandback’s yarn is Donald Judd’s 1976 untitled installation of 15 plywood boxes. Judd, an artist, philosopher and critic who died in 1994 at age 65, wanted to strip sculpture to its bare essentials. He used industrial materials—plywood, milled metal, Plexiglas—and had his sculptures made by fabricators. From a distance, his unpainted, roughly chest high boxes, which sit directly on the gallery’s floor with space to stroll among them, appear identical. But up close you can see that each of the boxes is slightly different, conjugating a vocabulary of open, closed, spliced and bisected forms. “It is a myth that difficult work is difficult,” Judd claimed. His idea that the context in which a sculpture or painting is seen is as important as the work itself—and essential to comprehending it—would become Dia:Beacon’s credo.

“Looking at Judd’s works, you start to think about limitless possibilities,” says Riggio (who with his wife, Louise, contributed more than half the $66 million it took to realize the museum). “You feel not just the brilliance of the artist himself, but you also feel the potential of the human spirit, which includes your own. You see what a great mind can do, so it’s more than about the art.”

“obviously, the model for what we are doing is in Marfa,” says Riggio, referring to the museum that Judd founded in an abandoned fort in West Texas cattle country in 1979. Judd hated conventional museums, and he likened permanent galleries, where works of several different artists are grouped in a single room, to “freshman English forever.” Judd came up with another way: displaying individual artists in buildings adapted to complement their art.

Judd’s idea of converting industrial buildings into galleries can be seen today in the raw spaces of the Los Angeles Temporary Contemporary and at MASS MoCAin North Adams, Massachusetts. But Judd’s cantankerous, visionary spirit finds its fullest expression at Dia:Beacon. “The artists represented at Dia, especially Judd, are really the founders of this place’s aesthetic,” says Govan. “I see this museum as a series of single-artist pavilions under one diaphanous roof of light.”

In 1977, Judd met German art dealer Heiner Friedrich, a man with a nearly religious zeal to change the world through art. In 1974, Friedrich and his future wife, Philippa de Menil, the youngest child of Dominique and John de Menil of the Schlumberger oil fortune, created the Dia Art Foundation. (Dia, the Greek word for “through,” is meant to express the foundation’s role as a conduit for extraordinary projects.) Over the next decade, Friedrich and Philippa gave millions of dollars to finance works by artists they admired. Typical of those the couple funded was Walter De Maria’s 1977 Lightning Field—400 stainless-steel poles set in a one-mile-by-one kilometer grid in the New Mexico desert.

In 1979 Dia began purchasing the abandoned Texas fort and its surrounding 340 acres at the edge of Marfa for Judd, who, according to Riggio, “turned an army barracks into what I think is easily the best single-artist museum in the world.” Then, in the early 1980s, Friedrich’s dominion began tumbling down. There was an oil glut. Oil stocks crashed, and Dia ran out of money. Friedrich resigned from the board and a new board instituted a reorganization. Dia’s new mission did not include funding gargantuan artistic projects.

Judd’s contract gave him the Marfa property, the art it contained and a legal settlement of $450,000. He reconstituted his Texas enterprise as the Chinati Foundation, named for the surrounding mountains, and commissioned such artists as Claes Oldenburg and Ilya Kabakov to create new works. Some other Dia art was sold, allowing a new director, Charles Wright, to open the DiaCenter for the Arts in 1987 in the Chelsea section of Manhattan, where the foundation continues to mount single-artist exhibitions.

In 1988, Michael Govan, then just 25 and deputy director of New York’s Guggenheim Museum, visited Judd in Marfa, an experience he calls “transformative.” Afterward, Govan says, “I completely understood why Judd had abandoned working with other institutions and made his own. Other museums were concerned with admissions revenue, marketing, big shows and building buildings that people would recognize. And all of a sudden I see Judd with this simple situation, this permanent installation, taking care of every detail in the simplest way. And the feeling was something you could be entirely immersed and lost in.” Two years later, Govan accepted the directorship of the scaled-down Dia. “I knew it was the one place that held more of Judd’s principles than anyplace else,” he says, “whether there was money to execute them or not.” In fact, there was a $1.6 million deficit. But Govan’s agreement with Dia board members was that they would consider a permanent home for the collection if he could stabilize the finances. By 1998, the budget had been balanced for three years. That was also the year that Dia showed Torqued Ellipses, a new work by sculptor Richard Serra.

The three monumental sculptures—looming formations each twisted out of 40 to 60 tons of two-inch-thick steel plate—dominated the Chelsea gallery as they now (along with the latest in the group, 2000, a torqued spiral) dominate their space at Dia:Beacon. As you circle each behemoth, you are as aware of the sinuous spaces between the sculptures as of the forms themselves. But as you move inside the openings of the monoliths, everything changes. However bullied you might feel outside, once in, you feel calm.

Leonard Riggio, founder and chairman of Barnes and Noble, had scarcely heard of Dia when he went to see the Serra show. “It was magic to me,” he recalls. At Govan’s urging, he spent nearly $2 million to buy Torqued Ellipses for Dia, jump-starting its dormant collecting program. At about that time, Govan and curator Lynne Cooke, who had also come to Dia in 1990, began looking for space for a permanent museum. One day, flying some 60 miles north of New York City in a rented Cessna 172—Govan got his pilot’s license in 1996—they spotted a faded Nabisco factory sign on the banks of the Hudson River. Back in New York, Govan traced the building to the International Paper Corporation and drove up to see it on a wet spring day.

“So I walk into the building and it is spectacular,” he remembers. “I said, ‘Would they ever consider giving it to a museum?’ They said, ‘Absolutely not. This is for sale.’ ” In the end, however, International Paper donated the factory and the land to the museum, and Govan raised the money for the renovation through public and private contributions. The project (a three-way collaboration between Irwin, Govan and the New York City architectural firm OpenOffice) began in 1999. At the same time, Govan and curator Cooke were building the collection.

In 1994, Govan had learned that collector Charles Saatchi wanted to sell a rare group of paintings by the New Mexico based artist Agnes Martin. “It seemed to me that this work of art was very much like what Dia had collected,” he recalled. “It was a big epic—really a major work.” But Govan was too late; the paintings had already been sold to the Whitney. “So I asked if she would consider doing another series,” Govan says. Martin didn’t respond. “Then, in 1999, I get a call saying that Agnes is working on the Dia paintings, and they are really important to her. I said, ‘What?’” Without telling Govan, Martin, now age 91 and still painting, had taken up the challenge and gone ahead with the project.

Today her Innocent Love occupies an entire gallery at Dia: Beacon. The paintings play variations on shimmering bands of color. Her Contentment consists of six vertical bands of pale yellow; Perfect Happiness is a series of vertical washes that translate as little more than a glow on the retina. The paintings reflect the shifting quality of desert light, making the gallery seem as spacious as New Mexico’s vistas.

Serra’s Torqued Ellipses have quite the opposite effect. They overpower the factory’s long train shed, into which they are wedged. Serra chose the space himself. “You hardly ever get to do that in a museum,” he says. “I don’t think there’s another museum in the world like this. If you can’t find someone to look at between Warhol, Judd, Flavin, Martin and Ryman, it’s not the art’s fault.”