Best. Gumbo. Ever.

He ate far and wide, but the author found only one true version of the New Orleans dish—Mom’s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Unified-Theory-Gumbo-631.jpg)

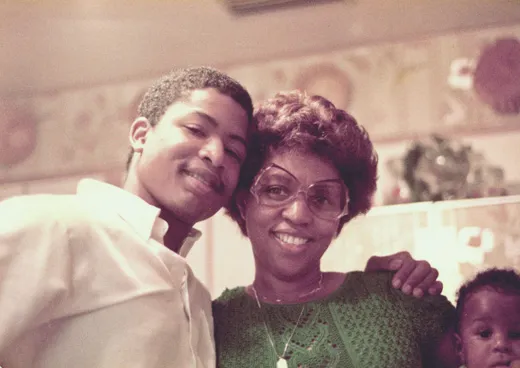

Every south Louisiana boy is honor-bound to say that his mother makes the world’s best gumbo. I am distinguished from the rest of my tribe in that regard in this one particular:When I make that claim, I am telling the truth.

Print out the recipe for Mrs. Elie's gumbo.

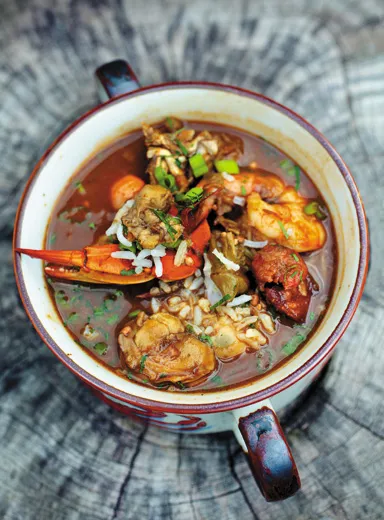

My mother’s gumbo is made with okra, shrimp, crabs and several kinds of sausage (the onions, garlic, bell pepper, celery, parsley, green onions and bay leaf go without saying). My mother’s gumbo is a pleasing brown shade, roughly the color of my skin. It is slightly thickened with a roux, that mixture of flour and fat (be it vegetable, animal or dairy) that is French in origin and emblematic of Louisiana cooking. When served over rice, my mother’s gumbo is roughly the consistency of chicken and rice soup.

My mother’s was not the only gumbo I ate when I was growing up. But my description of her gumbo could easily be applied to most of the gumbo made by our friends and relatives. Or, to put it another way, I was aware of a spectrum, a continuum along which gumbo existed. A proper gumbo might contain more of this or less of that, but it never ventured too far from that core. With one notable exception. My elders acknowledged the existence of two types of gumbo: okra and filé. Filé, the ground sassafras leaves that the Choctaw contributed to the state’s cuisine, thickened and flavored gumbo. By the time I came along, okra could be bought frozen year-round. So if you really wanted to make an okra gumbo in the dead of winter, you could. But in my parents’ day, filé gumbo was wintertime gumbo, made when okra was out of season. Since filé powder wasn’t seasonal, it was often added to okra gumbo at the table for additional flavor. Wieners, chicken meat and giblets—these things appeared in some people’s gumbos and perhaps they liked them there. But I aways viewed them as additives, inexpensive meats used to stretch the pot.

Gumbo for me and my sister meant hours peeling shrimp or chopping seasoning a day or two before a major holiday. It meant the first course of Thanksgiving or Christmas dinner. It meant an appetizer as filling, rich and complicated as the many courses that followed it. Gumbo meant that God was in His heaven and all was right with the universe.

The cracks in said universe began to reveal themselves in the 1980s. As the Cajun craze had its way with America, I began to hear tourists, visitors and transplants to New Orleans praising this or that gumbo for its thickness and darkness. This was strange to me. Gumbo was supposed to be neither thick nor dark. Even more important, “dark” and “thick” were being used not as adjectives, but as achievements. It was as if making a dark gumbo was a culinary accomplishment on par with making a featherlight biscuit or a perfectly barbecued beef brisket. Naturally, I viewed these developments with suspicion and my suspicion focused on the kitchen of Commander’s Palace and its celebrated chef, Paul Prudhomme.

Prudhomme hails from Cajun Country, near Opelousas, Louisiana. He refers to his cooking not so much as Cajun, but as “Louisiana cooking,” and thus reflective of influences beyond his home parish. For years I blamed him for the destruction of the gumbo universe. Many of the chefs and cooks in New Orleans restaurants learned under him or under his students. Many of these cooks were not from Louisiana, and thus had no homemade guide as to what good gumbo was supposed to be. As I saw it then, these were young, impressionable cooks who lacked the loving guidance and discipline that only good home training can provide.

My reaction was admittedly nationalistic, since New Orleans is my nation. The Cajun incursion in and of itself didn’t bother me. We are all enriched immeasurably when we encounter other people, other languages, other traditions, other tastes. What bothered me was the tyrannical influence of the tourist trade. Tourist trap restaurants, shops, cooking classes, and at times it seemed the whole of the French Quarter, were given over to providing visitors with what they expected to find. There was no regard for whether the offerings were authentic New Orleans food or culture. Suddenly andouille sausage became the local standard even though most New Orleanians had never heard of it. Chicken and andouille gumbo suddenly was on menus all over town. This was the state of my city when I moved back here in 1995.

In an attempt to create an understanding of all of this for myself, I did an essay for CBS News’ “Sunday Morning.” In the course of that piece, I asked Bernard Carmouche, then the chef de cuisine at Emeril’s, about some of the gumbos they had served at the restaurant. In addition to the usual assortment of meat-based gumbos, he mentioned goat cheese gumbo and truffle gumbo, which were even beyonder the pale than I had imagined. Emeril’s was not distinguished in this regard. I imagined that sauciers, struck by inspiration or stuck with leftover odds and ends in the walk-in cooler, created soups with these disparate parts and then attempted to elevate the concoction by labeling it with the good name of gumbo.

I was confident in my perspective until recently, when my friend Pableaux Johnson decided to dedicate much of his waking life to making smoked turkey and andouille gumbo. Pableaux, a New Orleans-based food and travel writer, was raised in Cajun Country. Gumbo for him and his people could hardly have been more different than it was for me and mine. For him, gumbo was an everyday dish. It sometimes was seafood- and okra-based, especially in the summer, but seafood was not required. The gumbo Pableaux makes reminds me of stewed chicken. If you put turkey and sausage into the thick gravy of stewed chicken, if you made enough gravy so that the dish was closer to the soup side of the soup-stew continuum, you would have a gumbo much like Pableaux’s.

How can this dish be reconciled with the gumbo of my youth? The truth is that “gumbo” has long been a catchall word. In The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book, there are ten recipes, ranging from the conventional (shrimp gumbo, crab gumbo, okra gumbo) to the exotic (squirrel or rabbit gumbo, cabbage gumbo). Originally published in 1900, this book is focused on New Orleans, so these gumbo variations don’t even take into account all the different approaches that dot the countryside.

Some of these differences in gumbo can be attributed to the different etymologies of the word. Kingombo is the word for okra in many Bantu languages in West Africa, and I believe it to be the origin of the name of the okra-based soups of Louisiana. But the Choctaw Indians called their ground sassafras leaves gombo or kombo, not filé. Thus the Choctaw word and the ingredient for which it stands could well be the origin for the thick, non-okra soup stews that also share the gumbo name. As for the third theory for the origin of gumbo, the fanciful belief that gumbo has its origins in the bouillabaisse of Provence, the evidence for that connection is as laughable as it is invisible.

Perhaps there has never been a day on this continent when the word “gumbo” meant something precise and specific. Lafcadio Hearn’s 1885 La Cuisine Creole, considered the first Creole cookbook, codified the idea of gumbo as leftover wasteland. “This is a most excellent form of soup, and is an economical way of using up the remains of any cold roasted chicken, turkey, game, or other meats.” Later he suggests “green corn” can also be included.

I recoil from this laundry list of additives in part because of something my mother used to say. She didn’t like a poor man’s gumbo. Meaning, not that poor people couldn’t eat gumbo, since that position would have ensured that she would have been denied that pleasure for all of her youth. Rather, she meant that if you didn’t have the proper ingredients to make a real gumbo, you should make another dish. Hearn redeems himself to an extent. While the instructions for “gombo” created from leftovers are in a headnote, the proper recipes are all for gumbos that would meet my mother’s strict standards. They feature oysters, chicken, shrimp, crabs and “filee.”

Try as I might, I can’t help but feel that vague, all-inclusive definitions of gumbo disrespect its essence. Gumbo has earned reverence in a way that few dishes have. It is the signature culinary achievement of one of the world’s great culinary capitals. It is as much at home on a family’s holiday dinner table as it is on the menus of the city’s finest restaurants. It embodies Africa, Europe and Native America with a seamless perfection. Yet the fact that any second-rate saucier feels entitled to misuse the name with callous abandon irks me in ways that no one who has ever enjoyed cow foot gumbo with corn kernels and truffles can possibly understand.