Better Feet Through Radiation: The Era of the Fluoroscope

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120404094006shoecard_470.jpg)

In the 1940s and ’50s, shoe stores were dangerous places. At the time, however, few people were aware of this. In fact, to the average kid being dragged by her parents to try on new Mary Janes, the shoe store was a far more exciting place back then than it is now. At the center of the shopping experience was the shoe-fitting fluoroscope—a pseudoscientific machine that became a token of mid-century marketing deception.

The fluoroscope’s technology was not in itself a sham—the machine enabled shoe salesmen to view their clients’ bones and soft tissue by placing their feet between an X-ray tube and a fluorescent screen. The patent holder, a Bostonian doctor, had realized that this awe-inspiring medical technology would be a great tool for stimulating retail. However, the stated utility of the machine—to provide customers with a better-fitting shoe—doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. “The shoe-fitting fluoroscope was nothing more nor less than an elaborate form of advertising designed to sell shoes,” state Jacalyn Duffin and Charles R. R. Hayter, in a journal article in the University of Chicago’s The History of Science Society:

It entered a well-established culture of shoe-selling hucksterism that relied on scientific rhetoric; it took advantage of the woman client newly accustomed to the electrification of her home and the patter of experts’ advice about ‘scientific motherhood’; it neatly sidestepped the thorny problem of truth in advertising that became an issue in the interwar years; and it enticed thrill-seeking children into shops where salesmen could work their magic.

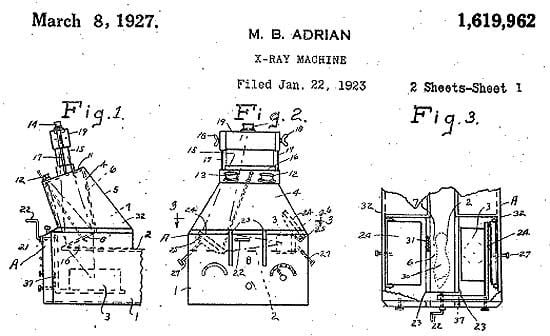

During its height, the fluoroscope was an essential interior design feature—the Barcelona Chair of the shoe store—signaling the shop’s advanced awareness of technology and style. The device looked like a small wooden cabinet or podium, with a compartment toward the bottom of one side for the customer’s foot, and several viewing scopes on top that often varied in size—a large one for the salesman (presumably always a man), a medium-size one for the parent (presumably always the mother, and therefore “smaller in stature”), and the littlest one for a child.

The subtle sexism of the eyepiece design reflected the important connection between the fluoroscope’s widespread adoption and the role of women in this era. In The Modern Boot and Shoe Maker Written by Practical Men of Wide Experience (world’s greatest book title, 1917), salesmen were advised that manipulative and commanding tactics were not only appropriate, but advantageous for moving their inventory: “With a lady, it is completely effective to suggest that is hopelessly out of fashion.”

Further, they were encouraged to convey to mothers, implicitly or directly, that dressing their children in shoes that were too small was a moral failing. As the alleged inventor Dr. Lowe wrote in his application for a U.S. patent, “With this apparatus in his shop, a merchant can positively assure his customers…parents can visually assure themselves as to whether they are buying shoes for their boys and girls which will not injure and deform the sensitive bones and joints.”

The fluoroscope represented a particular early form of transparency for consumers, enabling them to see with their own eyes whether a shoe was pinching their toes or compressing their foot, and then presumably make an informed decision. But while an X-ray is literally transparent, there remained a wall between the salesman and the customer that would almost certainly crumble in the information age.

Fluoroscope manufacturers spoke two different languages—one was for retailers, the other for consumers. To the retailers, they blatantly encouraged deception in the interest of increased sales, while to consumers they expressed an earnest belief that their product guaranteed a better fit and healthier feet. Today it would be much more difficult for a corporation to maintain such contradictory messaging. Even then, they couldn’t snow everyone.

While thrill-seeking children lined up to stick their feet in the machine, fluoroscopes everywhere were leaking radiation at a rate far exceeding the maximum allowable daily dose set out in national standards. Even in the course of a short visit, customers received unsafe levels of exposure, to say nothing of the people who worked in the stores. There was a meme at the time related to radiation and nuclear research, calling individuals harmed or killed by exposure “martyrs to science.” When alarms began to sound around the use of fluoroscopes for retail sales, the meme was tweaked “to point out that the irradiation of shoe store employees could make them ‘martyrs to commerce.’”

Eventually the industry associations lost out to the proliferation of medical evidence warning of the dangers of fluoroscopes. Fluoroscopes were banned in most states by the late 1950s, replaced by the cold and far less exciting sliding metal measuring device that’s still in use today. But X-ray fittings aren’t entirely forgotten. Both my parents recall sticking their young feet in the box and watching their bones appear on the screen. “We didn’t do it very often,” my dad assures me, “although Mom sometimes notices that my feet glow under the covers.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)