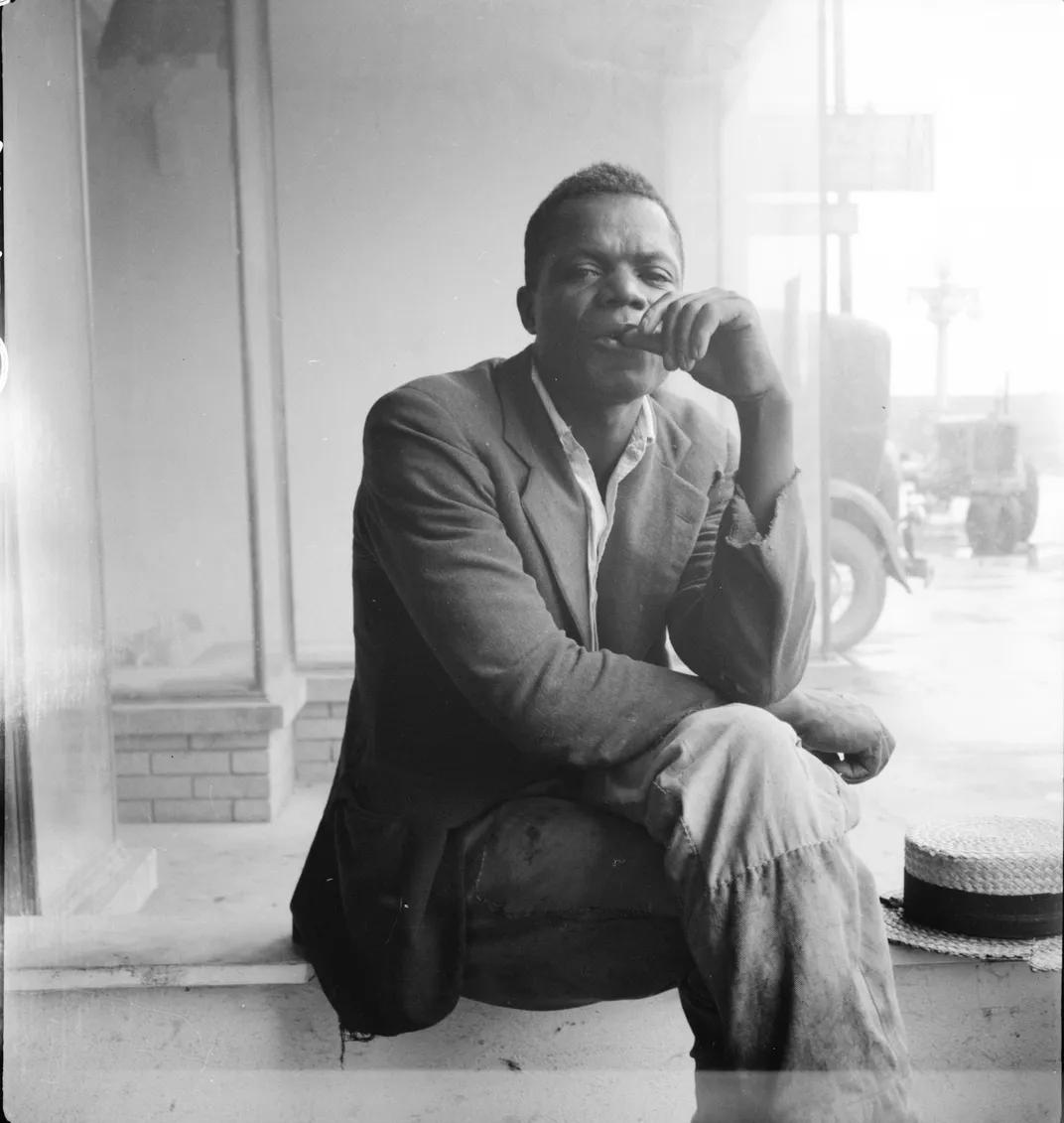

Not much is known about the black man photographed in 1936 in Greensboro, Alabama, by Dorothea Lange, who was on assignment for the Farm Security Administration. He sits, gazing directly at the camera, with his hand at his lips—as if he’s deep in thought—his legs crossed, and his hat in his hand. But when contemporary artist Bisa Butler made a life-sized portrait of this man using fabric and thread, she had a lot to say. She dressed him in vibrant colors and patterns, including a fabric printed with airplanes, to suggest that he’d traveled the world. She imagined him as a writer, poet or philosopher.

“I’m trying to give my subjects back an identity that’s been lost,” she says.

Butler uses her unique artistic style, which combines portraiture and quilting, to accord dignity and respect to her black subjects—those she discovers in historical photographs, as well as members of her own family. In the coming months, more and more of the public will have a chance to experience Butler’s work. Originally scheduled to debut earlier this year, her first solo museum exhibition, “Bisa Butler: Portraits,” opens at the Katonah Museum of Art in Katonah, New York, this weekend, and this fall, the exhibition is scheduled to travel to the famed Art Institute of Chicago, which recently acquired one of Butler’s artworks. That kind of exposure is rare for a contemporary artist making quilts. (Butler was also part of a 2010 satellite exhibition orchestrated by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.)

“Her work is, and has always been, about black identity,” says Michele Wije, the curator of the Katonah Museum exhibition, who now works at the American Federation of Arts. “So, the work is very relevant to this moment in history, when we are seeing a societal reckoning over racial inequity.”

Glenn Adamson, an independent craft scholar, curator and writer, who is not involved in the exhibition, observes, “Butler is elevating the status of her subjects by making portraits, and also elevating quilting—which is an African American craft tradition—by adding portraiture to it.”

Butler, who is in her 40s and based in New Jersey, didn’t set out to be a quilter. She studied painting at Howard University, and then earned a master’s in art education at Montclair State University, where she took a fiber art class. At the time, around 2001, her grandmother was sick, and she wanted to make something for her. So, she made a quilt, based on a vintage photo of her grandparents on their wedding day. That’s when she began developing her process.

She enlarges a photograph to life size, and then sketches over it, isolating areas of light and dark. Then, she begins choosing fabrics, layering them and stitching them together with a sewing machine, a process called appliqué. At the end, the stitched portrait is layered on top of soft batting and a backing fabric. A repeated pattern of stitches is applied to all three layers to hold them together—thus completing the quilt. One quilt can take hundreds of hours to complete.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/4e/a74ecf42-7941-48bf-983b-466f3eb1f834/lessapeurs.jpg)

Butler’s quilts explode with color, and every fabric has a specific meaning. “I use West African wax printed fabric, kente cloth and Dutch wax prints to communicate that my figures are of African descent and have a long, rich history behind them,” Butler says. She never uses natural skin tones. “I choose bright technicolor cloth to represent our skin, because these colors are how African Americans refer to our complexions,” she adds.

At Howard, Butler mentored members of the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA), which sought to define a black art aesthetic that represents African Americans in a positive light. “My color scheme is very much in line with AfriCOBRA,” Butler says. “Some people call it the Kool-Aid colors. I didn’t set out to adopt those ideas, but I guess the indoctrination worked.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/be/cfbea11a-2bb6-47e2-bb7f-ea13f64f4da4/broomjumpers.jpg)

Butler worked for more than a decade as a high school art teacher, quilting at night, on weekends and over the summer. She exhibited wherever she could—in churches, community centers and the like. “Back then, my quilts weren’t life-sized, because I didn’t have enough time for that,” she recalls. “I knew I could tell more of a story with the full body, and multiple people. I always wanted to do more.”

A few years ago, she found representation with Claire Oliver Gallery in Harlem. “I had to start thinking about what I wanted to say to the world, and I decided I couldn’t just work from family photos,” she says. So she turned to a database of Depression-era photos—by Lange, Russell Lee and others—from the Farm Security Administration in the National Archives. The photos weren’t under copyright. When she searched “Negro,” she got 40,000 results.

“I like working from black-and-white photos,” she says, “because it gives me the freedom to put in the colors I feel belong there.” She conducts research about the time period and tries to find out everything she can about her subjects. But, in the end, she uses her imagination to fill in the details.

The title of the quilt depicting the unnamed Alabaman is I Am Not Your Negro, taken from the 2016 documentary about the author James Baldwin and racism in America. She says the title reflects that man she has invented: “I am a black man, an African American man, and I am not ‘your’ Negro. I am not an intellectual inferior to anyone.”

Another quilt is based on a 1941 photograph taken by Russell Lee, of three women chatting outside a church on Chicago’s South Side. Butler’s ecstatic colors and patterns emphasize the fact that these women were part of a thriving Black middle class. Her title, “The Tea,” refers to the black vernacular for gossip.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3f/ab/3fab0cfc-79a0-4633-801a-2b8224f6c22f/theequestrian.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/2a/f12a0080-3c81-4ba4-b570-02a858986e81/theprincess.jpg)

Butler’s mother is from New Orleans, and her father was born in Ghana. She sees herself as part of the African American quilting tradition, but she hopes that she’s taking that tradition into the future. Before the Civil War, some enslaved black women learned sewing, spinning, weaving and quilting in wealthy households, and some became highly skilled. After the war, these women began making quilts for everyday use, typically using scraps of fabric, and they passed down their skills to their descendants. One such quilter was Harriet Powers, whose quilt depicting Bible stories, made around 1885, is in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Certain characteristics came to be associated with African American quilts made in the rural South: improvisation; asymmetry; large-scale patterns; and bold, contrasting colors. In recent decades, a group of African American quilters from the remote, rural town of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, became famous for their work in this style.

Butler is adding something radically new to that tradition: portraiture. She’s among a group of contemporary black artists—Kehinde Wiley, Amy Sherald, to name a couple—who have adopted the portrait, historically reserved for European aristocrats, to tell the story of contemporary black identity. At the same time, “quilting has also become a very important material and reference point for contemporary African American artists,” observes Adamson. He cites the artist Sanford Biggers, who cuts up antique quilts and put them in his paintings. Butler names Wiley and Sherald, along with Faith Ringgold and Romare Bearden, as artists who have influenced her.

Her portraits confront the viewer directly. Wije observes, “It’s very unusual in portraits for the subject to be depicted head-on. It’s hard to get features right. It gives these works the effect of Byzantine icons, really. And, as the viewer, you’re forced to look the person in the eye.”

Butler says of her portraits of young black boys in particular: “When people look at my work, I want them to learn something. If you’re not black, and young black boys on the street make you feel nervous, I hope that it clicks, that this person is human, he has a soul, he has wants and dreams and wishes. I try to put all that in the gaze itself and the pose. So that people will be confronted with someone who is so human you must see them as an equal.”

Since the killing of George Floyd, Butler has seen increased interest in her work. “My subjects stand in defiance against racist stereotypes,” she says. “My work proclaims that black people should be seen, regarded and treated as equals.”

:focal(291x77:292x78)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/26/1f26a805-e85c-45cc-be31-e0f4162ca859/mobile_i_am_not.png)

:focal(582x148:583x149)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/86/188610d9-f6ad-4bf6-8a95-fff394e6f147/social_i_am_not_your_negro.jpg)