Black Tweets Matter

How the tumultuous, hilarious, wide-ranging chat party on Twitter changed the face of activism in America

:focal(541x168:542x169)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/28/c028611a-fb7c-4020-af4f-379d52c2bd30/sep2016_l01_coltwitter-web-resize.jpg)

In July 2013, a 32-year-old writer named Alicia Garza was sipping bourbon in an Oakland bar, eyes on the television screen as the news came through: George Zimmerman had been acquitted by a Florida jury in the killing of Trayvon Martin, an African-American teenager. As the decision sank in, Garza logged onto Facebook and wrote, “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” Garza’s friend Patrisse Cullors wrote back, closing her post with the hashtag “#blacklivesmatter.”

Though it began on Facebook, the phrase exploded on Twitter, electrifying digital avenues where black users were already congregating to discuss the issues and narratives that are often absent from the national conversation. A year later Black Lives Matter had become a series of organized activist movements, with Twitter its lifeblood. Since that first utterance, the phrase “Black Lives Matter” has been tweeted 30 million times on Twitter, the company says. Twitter, it can be said, completely changed the way activism is done, who can participate and even how we define it.

Black Twitter, as some call it, is not an actual place walled off from the rest of social media and is not a monolith; rather, it’s a constellation of loosely formed multifaceted communities created spontaneously by and for black Twitter users who follow or promote black culture. African-Americans use Twitter in higher concentrations than white Americans, according to the Pew Research Center on American Life, which found in 2014 that 22 percent of online African-Americans used Twitter, compared with 16 percent of online whites.

But there’s more, much more, to black Twitter than social justice activism. It’s also a raucous place to follow along with “Scandal,” have intellectual debates about Beyoncé’s latest video or share jokes. “These were conversations that we were having with each other, over the phone or in the living room or at the bar,” said Sherri Williams, a communications professor at Wake Forest University who has studied the impact of black Twitter. “Now we’re having those conversations out in the open on Twitter where other people can see them.”

**********

It’s not controversial to point out that ever since Twitter was created in 2006, it has changed the way people, millions of them, get their news, share information—and launch movements, particularly during the opening days of the Arab Spring, in 2010, and Occupy Wall Street, in 2011. While those early actions proved the social network’s ability to organize or rally protesters, they also revealed the difficulty of sustaining a movement after the crowds went away. The activism of black Twitter, by contrast, is more continuous, like a steady drumbeat, creating a feedback loop of online actions and offline demonstrations. Most important, it has led to ways—if slowly—of translating social awareness into real change.

Take “#OscarsSoWhite,” a thread started in January 2015—and re-ignited this year—by an attorney turned journalist named April Reign, who noted that the Oscar nominations did not include one person of color in the four major acting categories. The hashtag became national news, and sparked action from black directors like Spike Lee and actors like Jada Pinkett Smith, who boycotted the event. Chris Rock made it a central theme of his opening monologue, and the Academy pledged to double the number of minorities, including women of color, in its ranks by 2020.

#OscarsSoWhite they asked to touch my hair.

— April (@ReignOfApril) January 15, 2015

The ability of interactive digital platforms to record and broadcast events, as well as fact-check what news media say, has created a potent counterbalance to traditional news reporting. This summer, after five police officers were killed during a Black Lives Matter protest march in Dallas, Twitter users quickly exonerated a person who had been identified by police as a suspect—Mark Hughes, an African-American protester, who had been legally carrying a rifle at the scene, consistent with Texas gun laws. Two hours after the Dallas Police Department tweeted a photo of Hughes as a person of interest, users were posting photos and videos that showed him without the gun when the actual shooting was underway.

In the past, sorting out such a dangerous official misidentification would have taken days of separate individuals writing letters to newspapers and police, and the wrong might not have been corrected even then. But with Twitter, the record was set straight out in the open while TV crews were still covering the incident. Nowadays, outraged citizens can simply tweet, and in no time thousands or millions of comments are voiced, if not heard. These shifts may seem minor, but they are, in fact, critical. The proximity of the once-powerless to the very powerful is radical.

When news outlets covering the fatal shooting of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge this July used a mug shot of him from several years before, black Twitter users revived the campaign #IfTheyGunnedMeDown. The hashtag originated after Michael Brown was killed in 2014 by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, and outlets covering his death published a photograph of him snarling at the camera. Horrified by the implication in that choice—that Brown may have deserved to be shot—many black Twitter users sprang into action and began circulating a copy of his high school graduation photo, a defiant rebuttal to the narrative taking form around the 18-year-old college-bound kid. Soon, Twitter users were posting their own paired photos—one wholesome, one menacing—speculating which image the press would use “#IfTheyGunnedMeDown.” Likewise, the Twitter activism after the Baton Rouge killing called out the media representation of black shooting victims, and the way black bodies are criminalized not only during their lives, but in their afterlives as well.

Perhaps most significant, black Twitter—and the Black Lives Matter activists who famously harnessed it—have created a truly grassroots campaign for social change unlike anything in history. Black Past, an online historical archive, notes that while “Black Lives Matter drew inspiration from the 1960s civil rights movement...they used newly developed social media to reach thousands of like-minded people across the nation quickly to create a black social justice movement that rejected the charismatic male-centered, top-down movement structure that had been the model for most previous efforts.” #BlackLivesMatter has emphasized inclusivity to ensure that lesbian, gay, queer, disabled, transgender, undocumented and incarcerated black people’s lives matter too. This approach is prismatically different from what the old era of civil rights activism looked like. And the result has been to elevate the concerns of the people in those groups, concerns often ignored by mainstream media outlets before the movement.

For all its power as a protest medium, black Twitter serves a great many users as a virtual place to just hang out. There is much about the shared terrain of being a black person in the United States that is not seen on small or silver screens or in museums or best-selling books, and much of what gets ignored in the mainstream thrives, and is celebrated, on Twitter. For some black users, its chaotic, late-night chat party atmosphere has enabled a semi-private performance of blackness, largely for each other. It has become a meeting place online to talk about everything, from live-tweeting the BET Awards show to talking about the latest photograph of America’s first family, the Obamas. And a lot of this happens through shared jokes. In 2015, the wildly popular #ThanksgivingWithBlackFamilies let users highlight the relatable, often comical moments that take place in black households around the holidays.

What Twitter offers is the chance to be immersed and participate in a black community, even if you don’t happen to live or work in one. As Twitter allows you to curate who shows up in your stream-—you only see the people you follow or seek out, and those they interact with—users can create whatever world of people they want to be a part of. Black Twitter offers a glimpse into the preoccupations of famous black intellectuals, academics and satirists. Where else could you see the juxtaposition of comments from the producer Shonda Rhimes, the critic Ta-Nehisi Coates, the actress Yara Shahidi (of “Black-ish”) and the comedian Jessica Williams, all in a single stream?

Still, it’s the platform’s nature to mix their observations with those of everyday folk. Most social networks, including Facebook, Snapchat and Myspace, prioritize interactions that are largely designed to take place among small handfuls of people you just met or already know. Bridges between communities are few, which means that randomness is rare, as is the serendipity that connects strangers in new ways. “Most social networks are about smaller conversations,” said Kalev Leetaru, a senior fellow at George Washington University who studies social media. “Twitter is the only one where everyone is in one giant room where people are trying to shout over each other.” And this particularity of Twitter has made it an ideal megaphone for its black users.

More often than not, the point is irreverence. In July, following the news that Melania Trump had lifted portions of the speech that Michelle Obama gave in 2008 during the Democratic National Convention, the actor Jesse Williams tweeted “Ain’t I a woman?”—the title of a famous speech by Sojourner Truth—to his 1.6 million followers with the hashtag #FamousMelaniaTrumpQuotes. Twitter caught fire with jokes about what else Melania had plagiarized, like Martin Luther King Jr.’s "I have a dream," or "In West Philadelphia born and raised," from the theme song to “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.” The comedian W. Kamau Bell tweeted, "YOU'RE FIRED!"

"I have a dream" #FamousMelaniaTrumpQuotes

— jesseWilliams. (@iJesseWilliams) July 19, 2016

"YOU'RE FIRED!" #FamousMelaniaTrumpQuotes pic.twitter.com/c0G1RcQMPZ

— W. Kamau Bell (@wkamaubell) July 19, 2016

**********

Though most users of black Twitter may revel in the entertainment, the medium’s role in advancing the cause of social justice is the thing that most impresses historians and other scholars. Jelani Cobb, professor of journalism at Columbia University, said that it’s as vital as television was to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. This newest generation of the movement is defined by an inability to look away and a savvy about the power of images to effect change. Long before we had the videos to prove it, we knew what happened when black people came into contact with the police. Technology has made this actuality intimate, pushed it into our Twitter (and Facebook) feeds so that we are all forced to bear witness. People watching the grisly videos can’t escape the conclusion that if you are black, you are treated differently. Still, despite the power of those images, if past cases of police abuse are any guide, there’s little reason to think there will be official consequences.

Leetaru, the researcher, cautions against expecting too much from a social media platform alone. “People think of social media as a magic panacea—if we can get our message out there, then everything changes,” he said. “Even with mainstream media, you don’t change the world with a front-page article.” Historically speaking, “You think about the laws that we talk about today, the laws that are on the books? It was engaging the political system and getting those laws on the books that actually enacted the change.”

What black Twitter has done is alter the terms of the game. It’s proven itself a nimble, creative, provocative way to talk about race and inequality and culture. Sure, there is still much more to be done, but Twitter has made this a national conversation, and that’s a good start.

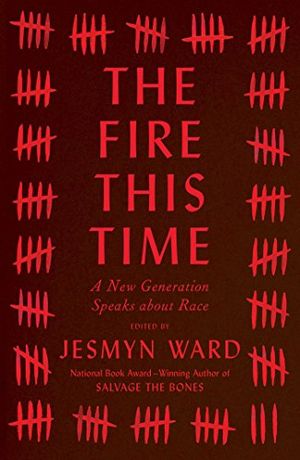

The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race