This Photo Book Is a Reminder That the Civil Rights Movement Extended Far Beyond the Deep South

Public historian Mark Speltz’s new book is full of images that aren’t typically part of the 1960s narrative

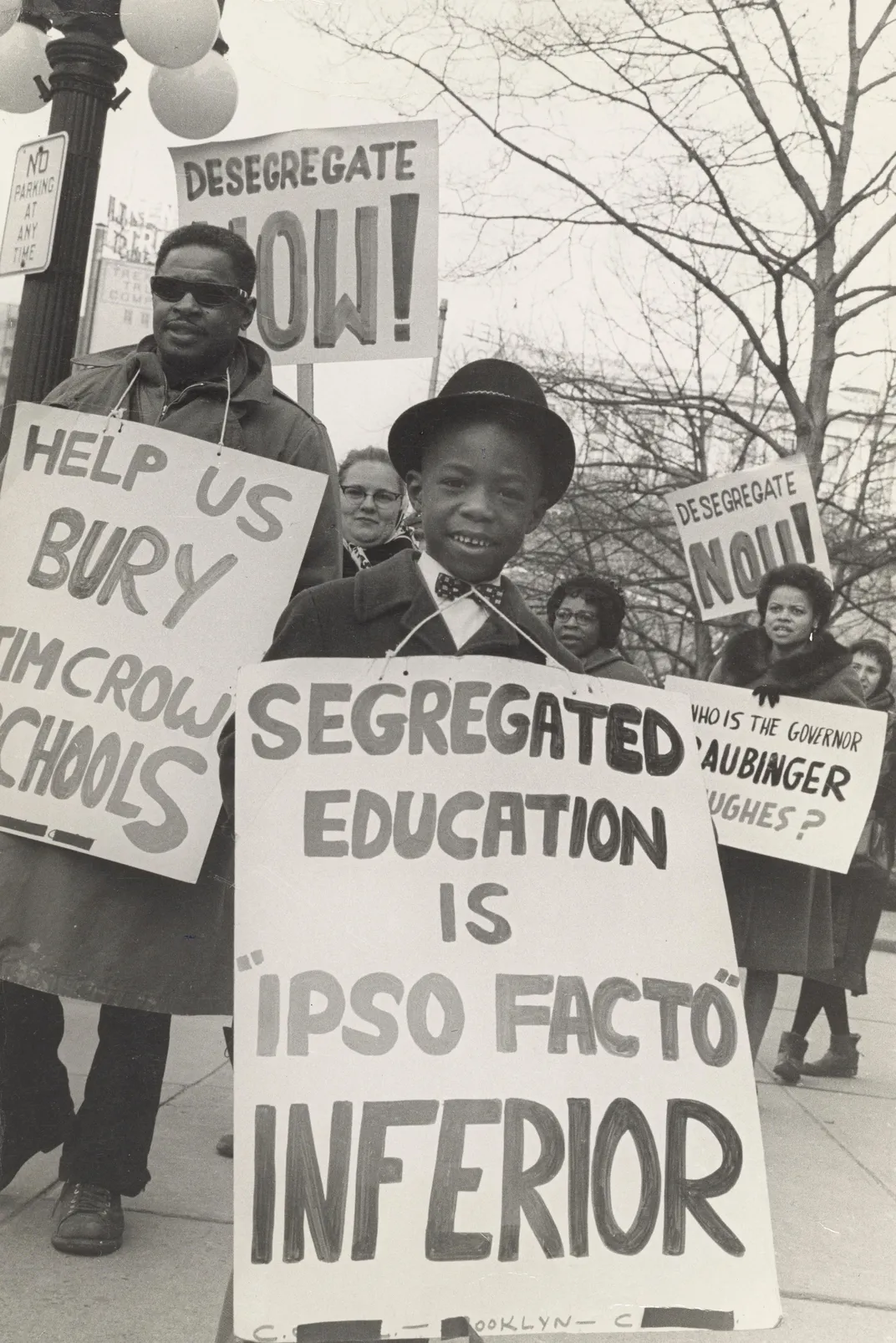

What images evoke the Civil Rights Movement? The struggle for equality is seen in photos of young African-Americans sitting at the Woolworth's counter in Greensboro, Dr. King leading marchers from Selma, or Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery. Each of these iconic images relays an important moment of the story of Civil Rights in the South.

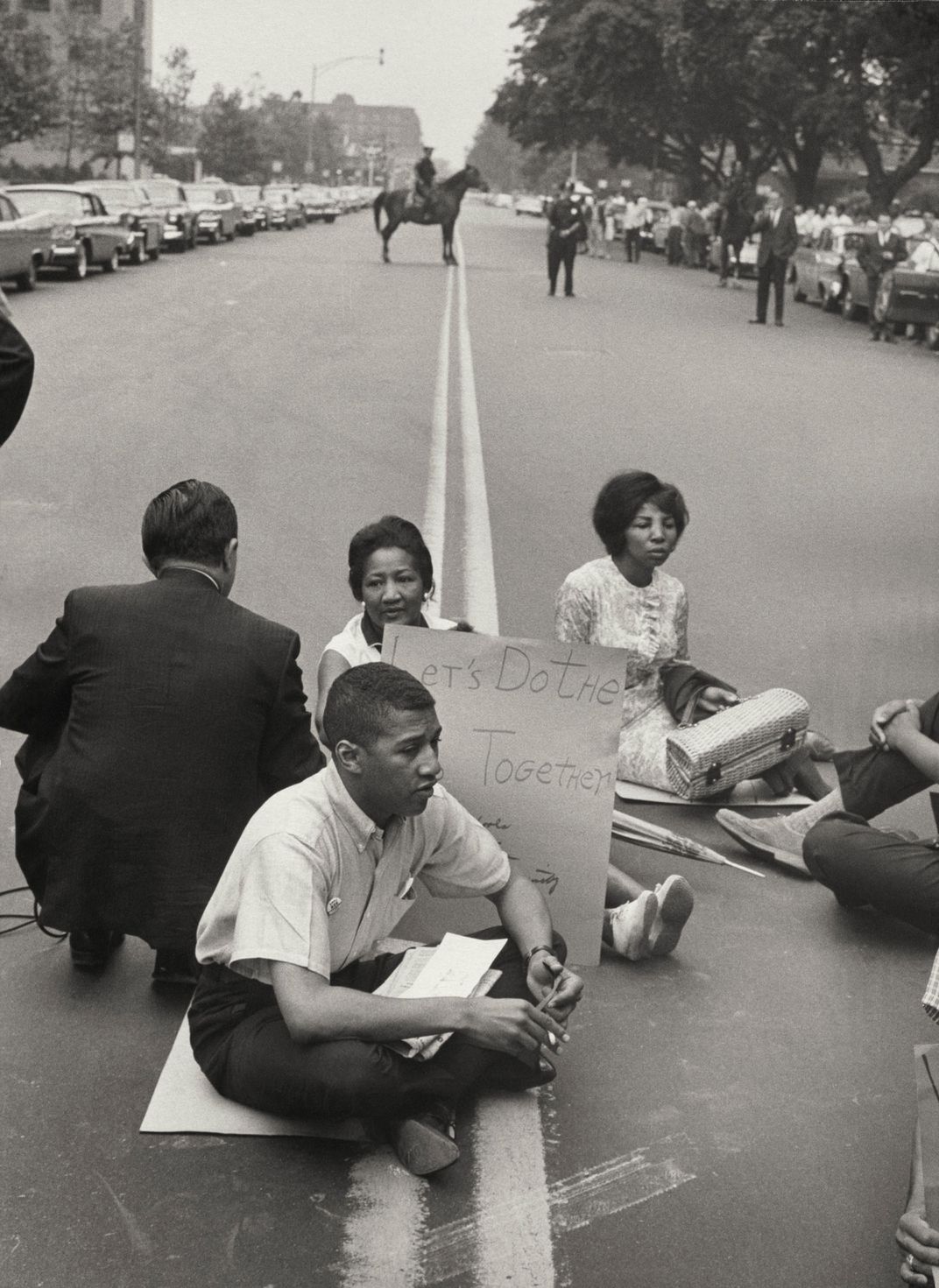

But the story is different in the North and the West, which lacks that kind of immediately iconic imagery. Not that there aren’t photographic counterpoints to the Southern stories; rather, these images have been missing from the boilerplate Civil Rights narrative. “If a kid opens a book today and finds the first photos of the North, they're normally Dr. King in Chicago in ’65, ’66, and then riots and rebellions,” says public historian Mark Speltz.

In his new photography book, North of Dixie: Civil Rights Photography Beyond the South, Speltz actively works to upend that narrative. Instead of focusing on the main touchstones of the movement in the South, he looks past that region to flesh out how the movement was conceived and led throughout the rest of the country.

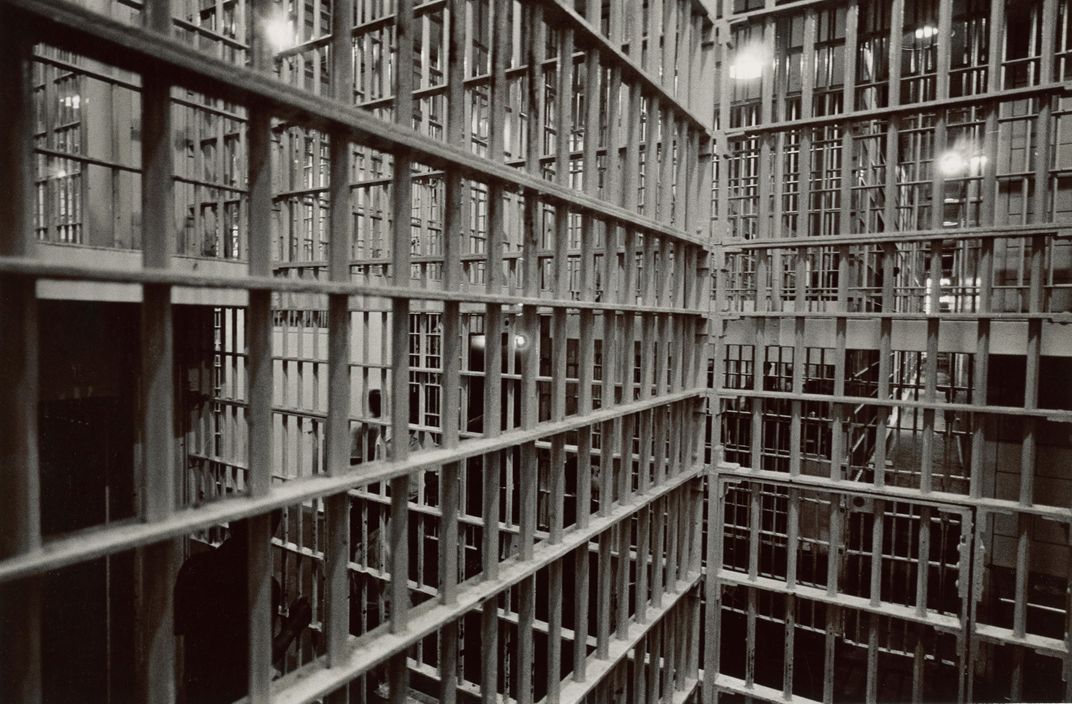

Speltz, whose day job is a senior historian at American Girl (yes, that America Girl), spent countless hours combing through local archives and tracking down people for permission to reprint photographs in order to provide an entry point to this history. The result, a 145-page book that contains approximately 100 photographs, is divided into four sections: “Northern Underexposure,” “The Battle for Self-Representation,” “Black Power and Beyond,” “Surveillance and Repression” along with an introduction and epilogue that discusses Civil Rights photography in the past and present.

He first decided to tell this story while pursuing a master’s of public history at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. There, he learned a different narrative of the story of civil rights from the one he was taught growing up in St. Paul, Minnesota. Like schoolchildren across the country, he could have told you the names of people like King and Rosa Parks, “the most cherished lessons and stories of the Civil Rights Movement,” but not about his own local history in the Midwest.

“Plumb the depths of your memory, and it's really hard to find those touchstones,” he says. He remembers learning about NAACP leader Roy Wilkins, and came to understand “urban renewal meant neighborhoods disappeared” when he saw local highways tear through African-American neighborhoods. But that was about it. The main lesson he was taught was that nonviolence was successful in the South. “It’s a feel-good story of cherished leaders, iconic moments,” says Spelt. But it doesn’t show the entire picture.

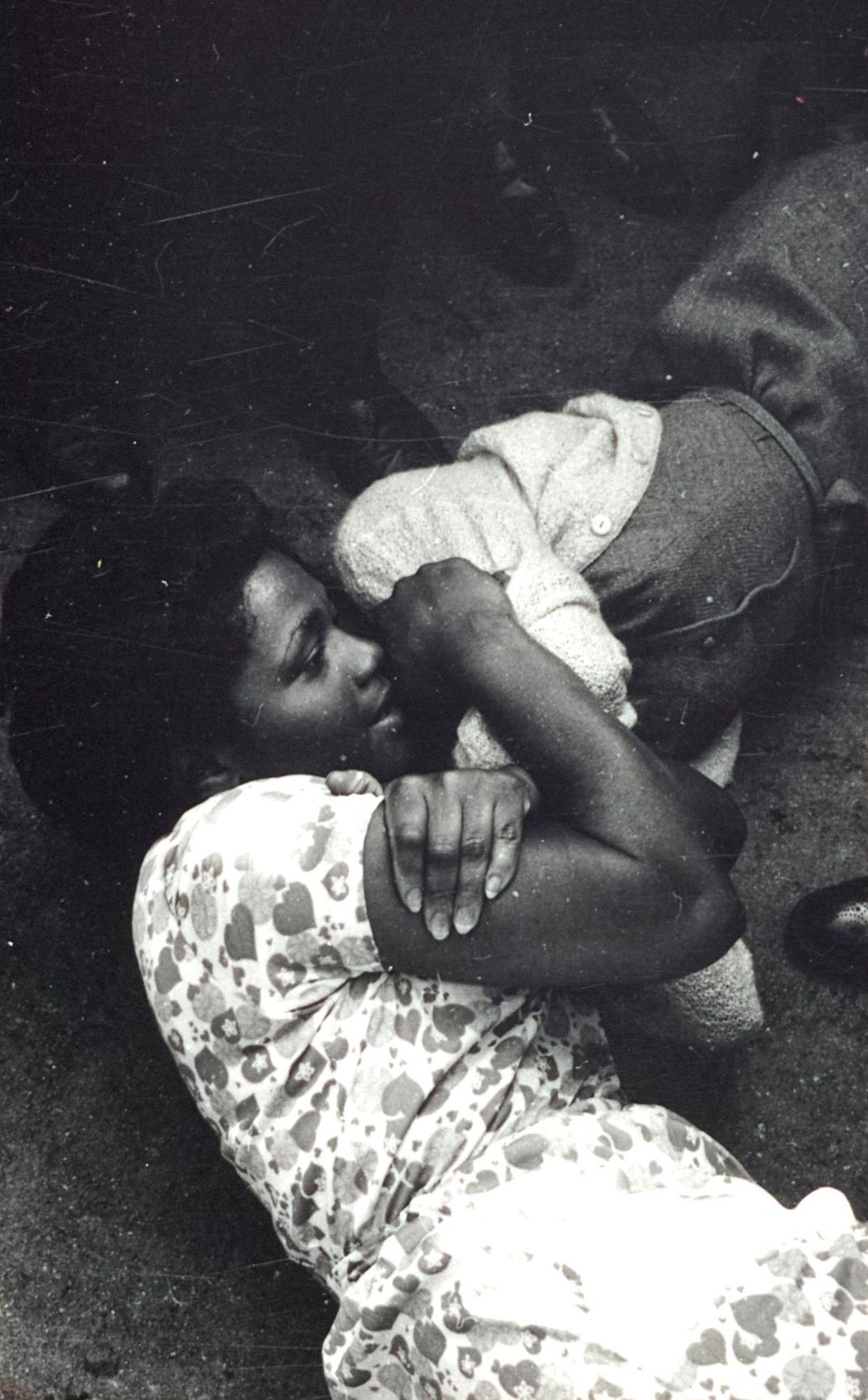

As the 20th century rang in, millions of African-Americans made the decision to leave behind the injustice of the Jim Crow South. Over the course of many decades, they packed up their belongings and headed north and west as part of the Great Migration. But the black diaspora found that while they could leave the South behind, Jim Crow segregation was not so easy to shake. Instead, it was repackaged in the form of white-only neighborhoods, unequal education and limited career opportunities. No wonder then, says Speltz, that the situation eventually boiled over. “When something blows up, it’s not wanton violence, it's a reaction to inaction,” he says.

But major media outlets didn’t focus that story. It was much easier to point the blame directly below the Mason-Dixon line. “Look at a Southern photograph that showed a snarling police dog,” says Speltz. “You could [downplay] the issue, and say, ‘That's not my community, it’s a little bit different. We don't have that problem here.’”

In the past few decades, though, the history books have changed. Important scholarship dedicated to regional stories like the early sit-ins in Wichita, Kansas, and the Black Panthers in Milwaukee have begun to tell the story of the Civil Rights Movement from local perspectives outside the South. Still, as Speltz parsed through these texts in graduate school, he found that much of the history was geared toward academics, not a general audience—and that photos were rarely part of the restored narrative. “Those photographs weren't making it into the larger picture,” says Speltz. “They were still being sort of overlooked.”

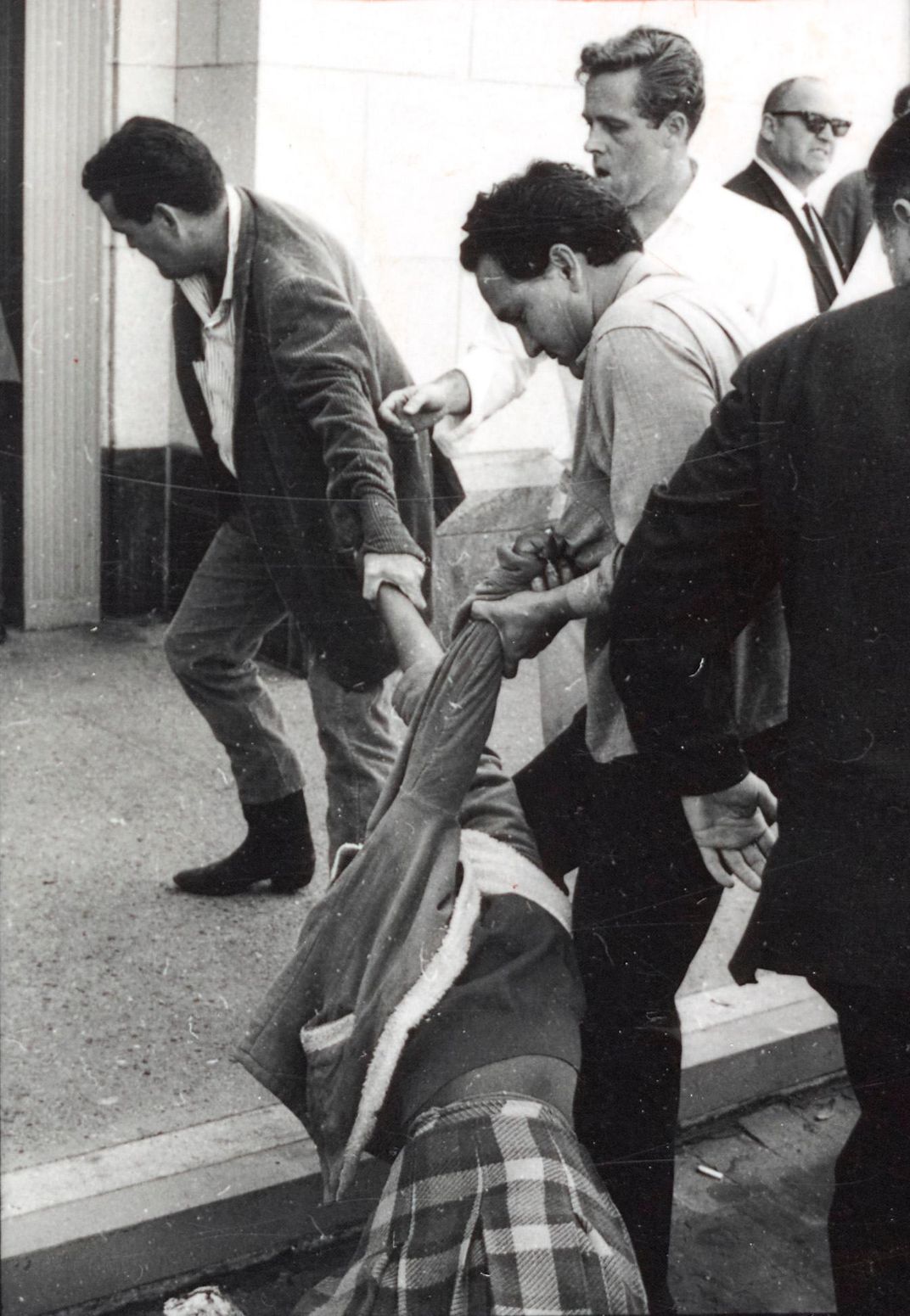

Paging through North of Dixie, it can make sense why some of the photos included wouldn't have made the cut to be printed in newspapers or magazines at the time. “Some of the photographs in here weren't used for a reason—either the newspaper didn't want to tell that story; the picture of the guy mopping didn't tell the right story," says Speltz. But he wanted to tell a larger story by including some shots that might have seemed like throwaways back then.

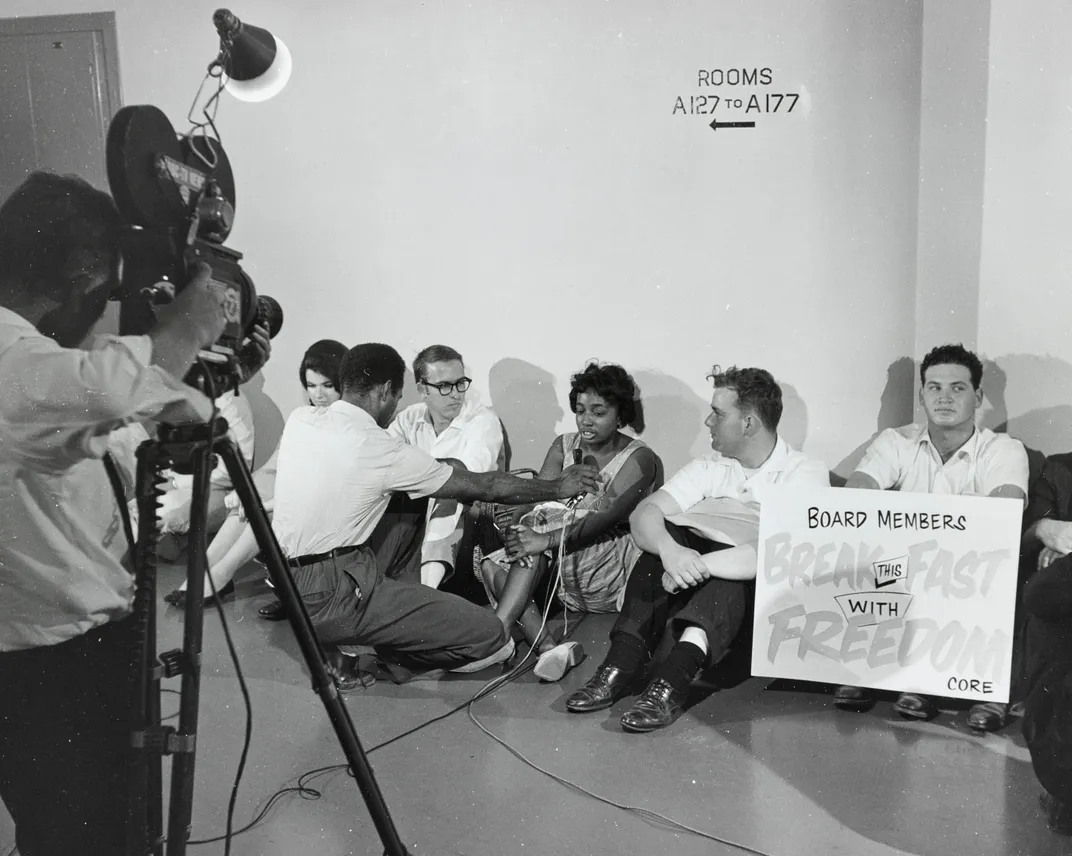

In 1963, activists on the West Coast participated in a hunger strike and sit-in outside the Los Angeles Board of Education offices. All were members of the Congress of Racial Equality or Core, which was founded in 1942, and was one of the important early organizations that championed Civil Rights. At the time the picture was taken, the activists had all been sitting there for eight or nine days. But the photograph, taken by documentary photographer Charles Brittin, isn't focused on them. Instead, it's zoomed out to document the news team recording them. "What he's capturing there is that the press is there, they're getting the attention, and he's able to document that," says Speltz. "That's what organizations were able to do with media outreach."

As it happened, while Speltz worked on North of Dixie, the Black Lives Matter movement began to explode on the national stage. So, as Speltz writes in the book, it's no coincidence that the historic photos included have modern-day resonance. “I haven't come to terms with how it impacted the book, but I know it did,” he says. One needs to look no further than the book’s cover to see what he means: It features a young, black boy with his hands up, his head turned, staring at armed National Guard members as they advance along a Newark sidewalk. “I saw that and was like, ‘Whoa.’ That happened 50 years ago,” says Speltz.

He found it impossible not to find echoes of the history he was uncovering in the news headlines, such as the story of Eric Garner, whose plaint of “I can’t breathe” before his death in police custody became a rallying cry across the country. “That happens and then you can't help but begin to see parallels,” he says.

Unlike in the 1960s, when organizations like SNCC had to work hard to share scenes from the frontlines of the movement, more people than ever can document this history today with their mobile phones. But though there may be more records of civil rights violations and struggles than ever before, Speltz worries that what activists are recording now won’t necessarily last. More must be done, he says, pointing to the important work coming out of places like Documenting Ferguson in St. Louis, to ensure that current photos are preserved in hard copy for the public historians of the future. “People are paying attention, but it’s [important to collect] citizen photography and [maintain] news organization photography so they don't disappear,” says Speltz.

While creating North of Dixie, Speltz came to appreciate the important role that the average person played in creating the Civil Rights Movement. “It's inspiring that you don't have to wait for a Dr. King, you don't have to wait for the most charismatic leaders to lead the way. It’s really up to everyday ordinary citizens,” says Speltz. When it comes to enacting change, he says, that same grassroots sentiment holds true today—as true as the unfamiliar, but unflinching glimpse into civil rights outside of the South that his work reveals.