A Brief History of Sending a Letter to Santa

Dating back more than 150 years, the practice of writing to St. Nick tells a broader history of America itself

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/f4/42f4b779-89cb-4873-b54b-94620f60e262/istock_000011199774_large.jpg)

“My pals say there is no Santa but I just have to believe in him,” writes 12-year-old Wilson Castile Jr., writing to the jolly fellow in 1939. Twelve might seem a bit old to believe in the portly resident of the North Pole. But Wilson, writing from his home in Annapolis, Missouri, seems worthy of extra sympathy. His explains in the letter that his father, a deputy sheriff, was shot and killed by gangsters and his new stepdad “is so mean he never buys me anything.”

Such sad or funny stories are not unusual when reading through Santa letters, going back to the 19th century. Notes sent to Santa are an unlikely lens through which to understand the past, offering a peek into the worries, desires and quirks of the times in which they were written. But as interesting as the children’s notes themselves are the changing ways adults have sought to answer them and their motivations for doing so.

Three new books shine a spotlight on mail addressed for Mr. Claus this season, telling the history of Santa letters from different angles: Letters to Santa , a selection of notes from 1930 to the present, selected from the thousands sent to the Santa Claus Museum in Santa Claus, Indiana (the city where Wilson Castile sent his letter); Dear Santa, which gathers earlier letters dated from 1870–1920; and The Santa Claus Man, my own book, which tells a true-crime tale of a Jazz Age huckster who abused a Santa letter–answering scheme to fill his own stockings with cash.

Together, the books illustrate how children’s requests and perceptions of Santa Claus changed over more than a century and a half. But they also reflect the durability and timelessness of the ritual, and how even when so much else about the world changes, children’s imaginations (and desire for toys) remain a constant.

This might seem surprising considering how the practice of Santa letters began. Early versions of Santa Claus tended to depict him as a disciplinarian. The first image of St. Nicholas in the United States, commissioned by the New-York Historical Society in 1810, showed him in ecclesiastical garb with a switch in hand next to a crying child, while the earliest known Santa picture-book shows him leaving a birch rod in a naughty child’s stocking, which he “Directs a Parent’s hand to use / When virtue’s path his sons refuse.”

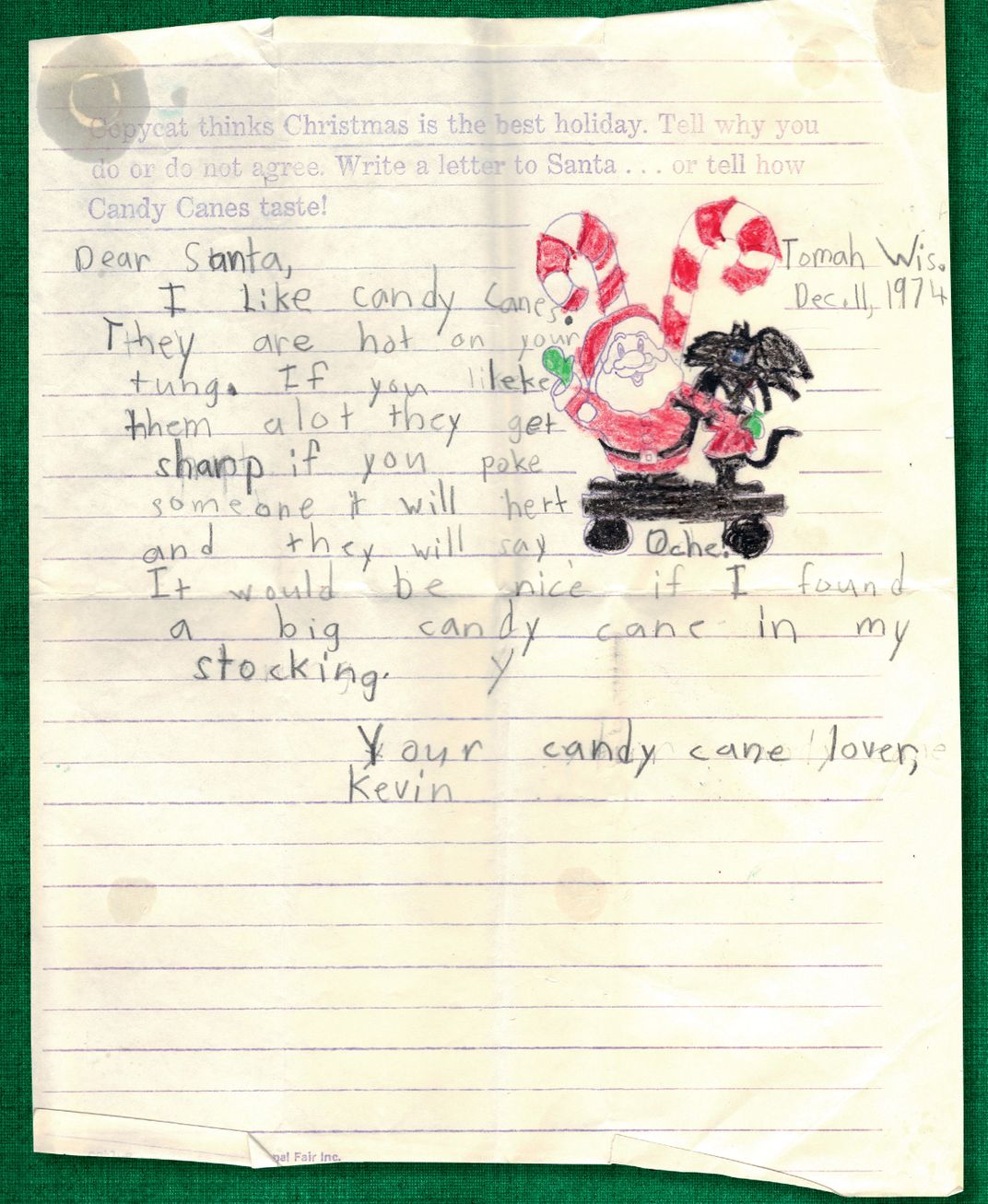

The earliest Santa letters are similarly didactic, usually coming from St. Nicholas, rather than written to him. The minister Theodore Ledyard Cuyler recalled receiving “an autograph letter from Santa Claus, full of good counsels” during his childhood in 1820s western New York. In the 1850s, Fanny Longfellow (wife of the poet Henry Wadsworth) wrote her three children letters each Christmas that commented on their behavior over the previous year and how they could improve it.

“[Y]ou have picked up some naughty words which I hope you will throw away as you would sour or bitter fruit,” Santa explained in an 1853 letter. “Try to stop to think before you use any, and remember if no one else hears you God is always near.” In an era before childhood was celebrated as a distinct period of a person’s life, gratifying kids’ imaginations was less important than teaching them manners that would speed them toward adulthood.

Longfellow’s letter bore a return address of “Chimney Corner,” likely because she left it on the family hearth. During these early decades of Santa’s evolution in the U.S., not only did the saint travel in and out of homes via the chimney, so did his mail. Parents left their notes to children by the fireplace, or in one of the nearby stockings, and soon children put their replies to him there.

As postal workers began hand-delivering mail to urban centers during the Civil War, Americans began to view the mail as a pleasant surprise arriving at one’s door, rather than a burdensome errand. The Chicago Tribune captured this shift in the experience of receiving mail in an 1864 story, commenting that the addition of 35 deliverymen had changed the city’s whole understanding of postage. Instead of “the annoyance of having to carry letters to the office,” now, as each postman brought mail directly to residents’ doors, it transformed the mail carrier into “a genuine Santa Claus [visiting] households on his beat.” As the postal system became more formalized and efficient, partly in response to the explosion of mail during the Civil War, the cost of postage began dropping in the mid-1860s. Parents grew more comfortable with paying for stamps, and children began to view the postman as an actual conduit to the Christmas figure.

Pictures, poems, and illustrations of St. Nick— particularly Thomas Nast’s 1871 depiction in the widely read Harper’s Weekly magazine —sorting letters from “Good Children’s Parents” and “Naughty Children’s Parents”— helped spread the idea of sending Santa mail. Nast is also credited with popularizing the idea that Santa lived and worked in the North Pole — for example, with an 1866 illustration that named “Santaclausville, N.P.” as his address — giving kids a destination to send Santa’s mail. The use of the post office to contact St. Nick began as a particularly American phenomenon. Scottish children would shout their wishes up the chimney, while Europeans simply left out stockings or shoes for the gift bringer.

Soon newspapers across the country were reporting the arrival of Santa letters to local postal departments, and then to their own offices (recognizing the emotional power of the letters, many papers published the children’s scrawls and even offered prizes for the “best” letters). “The little folks are getting interested about Christmas,” wrote a reporter for Columbia, South Carolina’s Daily Phoenix in December 1873. A correspondent for the Stark County Democrat, in Canton, Ohio, noted the following year: “One day last week two bright little children entered the Democrat office and wanted us to print letters to Santa Claus, from them.”

The gifts that kids requested in this period tended to be simple and practical. Dear Santa includes letters written during the 1870s that ask for gifts such as writing desks, prayer books, and “a stick of pomade” for “papa.” As society changed, the children started to ask for more fun items, such as candy, dolls, and roller skates.

But as the letters piled up, so did tensions about who should answer them. While some newspapers published letters sent to them and invited readers to respond, most missives sent to the post office ended up in the Dead Letter Office where they were destroyed, along with other mail sent to unreachable addresses. By the turn of the 20th century, the public and press began complaining that children’s wishes were treated with such neglect. Institutions ranging from charitable societies to the New York Times asked if an alternative could not be found.

After a few stopgap attempts, the Post Office Department (as the United States Postal Service was known until 1971), saw little other option but to permanently change the policy in 1913, allowing local charity groups to answer the letters, as long as they got the approval of the local postmaster. In Winchester, Kentucky, an organization began delivering Christmas goodies like nuts, fruits, candy—as well as firecrackers and roman candles—to letter writers. In the city of Santa Claus, Indiana, the city’s postmaster, James Martin, started answering the city’s large pile of Santa letters himself, then tapped local volunteers as the city’s name brought in ever-more mail for the man in the red suit.

But New York City had the most prominent letter-answering program. In 1913, customs broker John Gluck launched the Santa Claus Association, which coordinated the answering of tens of thousands of letters each year, matching children’s requests with individual New Yorkers who often hand-delivered the gifts to the letter writers. The effort earned accolades from the press, public and celebrities including John Barrymore and Mary Pickford. But each year, the group requested funds to cover ever-more gifts and postage costs, and even $300,000 to pay for a vast Santa Claus Building in Midtown Manhattan. Fifteen years after its initial launch, it was found that much of the money was unaccounted for and — as The Santa Claus Man tells in greater detail — Gluck was exposed as having pocketed much of the money (as much as several hundred thousand dollars in donations) for himself.

As a result, the Post Office Department revoked the Association’s right to receive Santa’s mail, and changed its policy nationally, restricting which groups could receive the letters. This led to the department’s establishment of Operation Santa Claus, at first an informal group of postal employees who pooled their own donations to send gifts in response to children’s pleas. The program evolved after being spotlighted in the climactic courtroom scene in Miracle on 34th Street in 1947, then enjoyed a significant boost when Johnny Carson made a practice of reading several letters each December on “The Tonight Show,” urging viewers to take part in the program.

“The range is incredible, from the very basic where they can’t afford to buy anything but a token, to the opposite end where they will invest in a school and redo a playground,” says Pete Fontana, the “Chief Elf Officer” in New York City, who has overseen the Operation Santa Program the past 17 years (though he will be retiring after this season). This program avoids fundraising by simply facilitating donations of willing donors. Individuals can volunteer to answer a Santa letter (or several), then it is up to that donor to buy the requested gift and bring it to the post office to send to the child. While the postal employees shuttle the gifts to children, it is the donors who pay for them. “It’s amazing how it can vary from almost nothing to the extreme,” says Fontana.

While post offices throughout the country managed most of these answering campaigns, the city of Santa Claus has taken its own approach. In 1976, a number of the local volunteers established Santa’s Elves, Inc., separate from the post office. In 2006, the Santa Claus Museum & Village opened, merging with the Elves. It is this organization that is behind the book Letters to Santa Claus, drawing on its archives of missives going back to the 1930s.

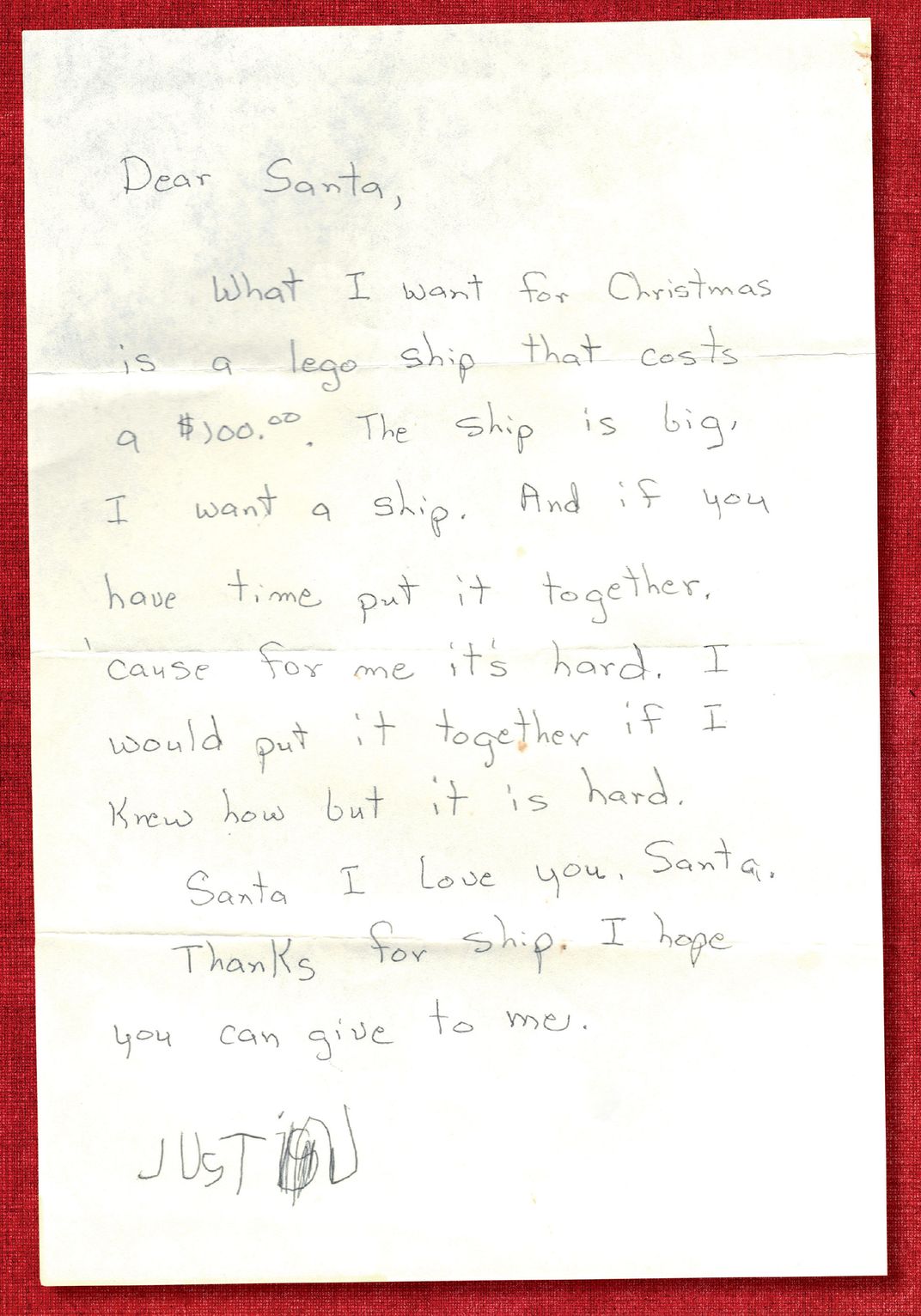

“It goes from very simple letters to far more expensive wish lists—you watch the progression from ‘I’d like some blocks’ to ‘I’d like a VCR’ and ‘I’d like an iPad,’” says Emily Weisner Thompson, the executive director of the museum who compiled Letters to Santa.

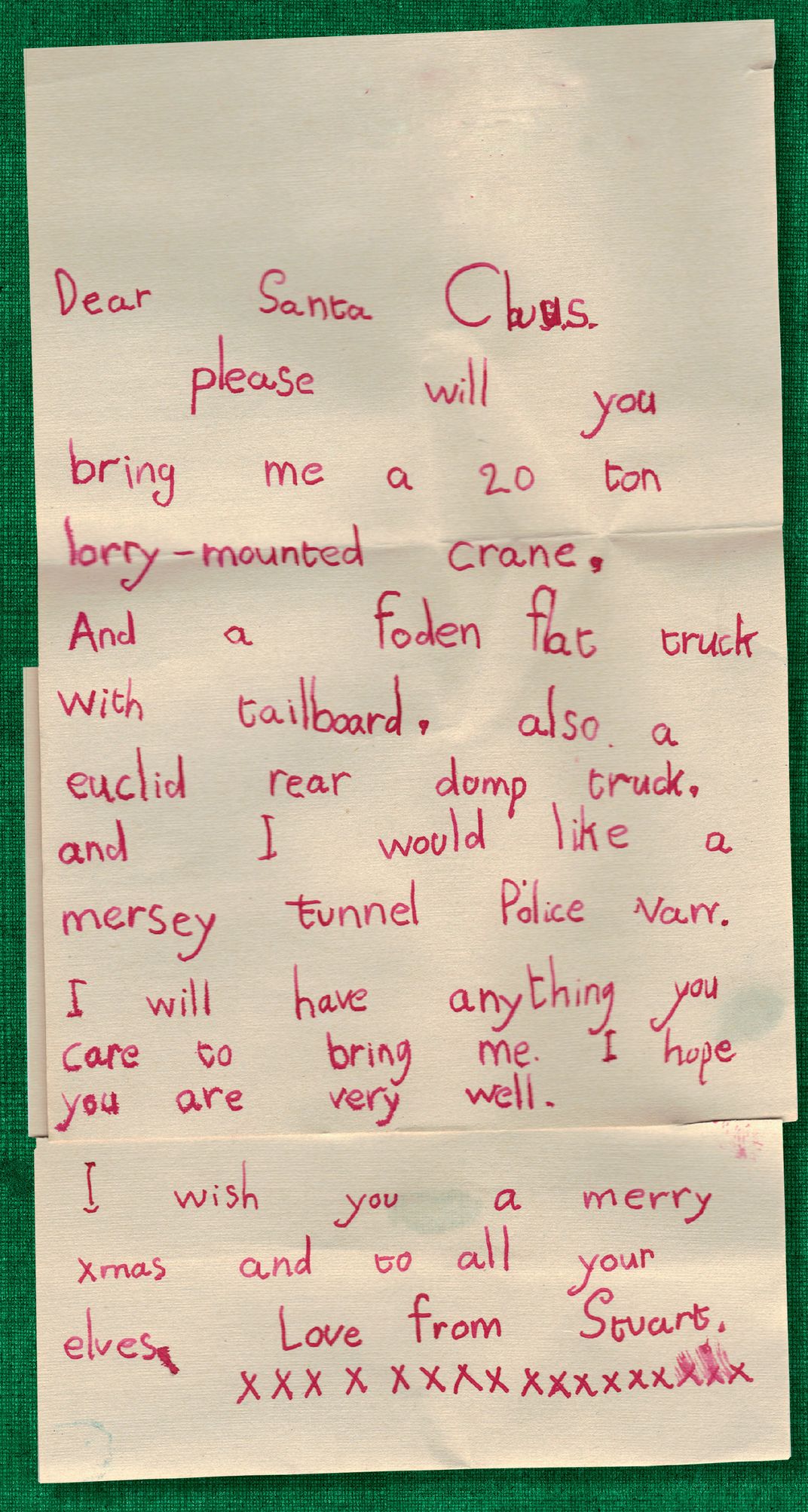

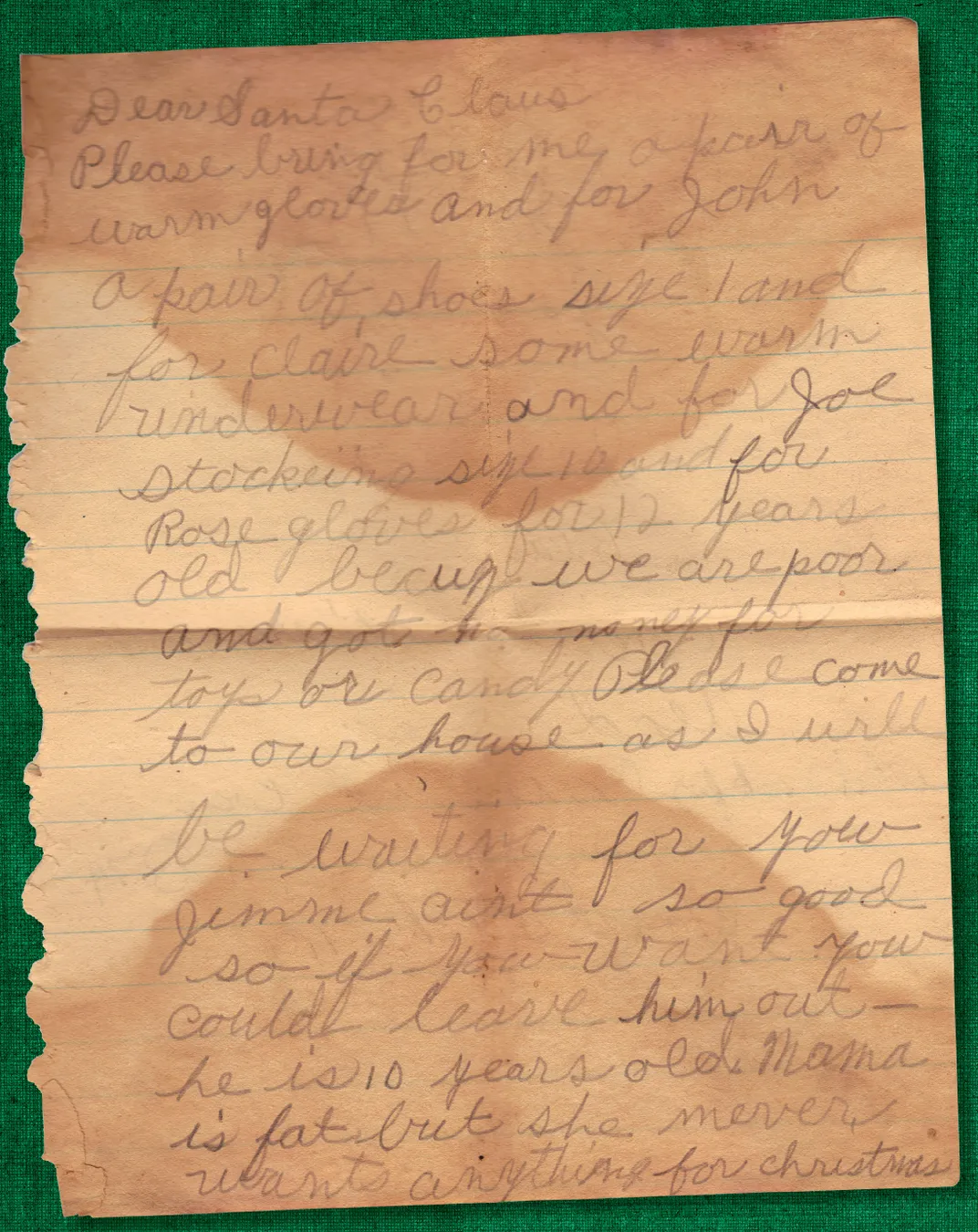

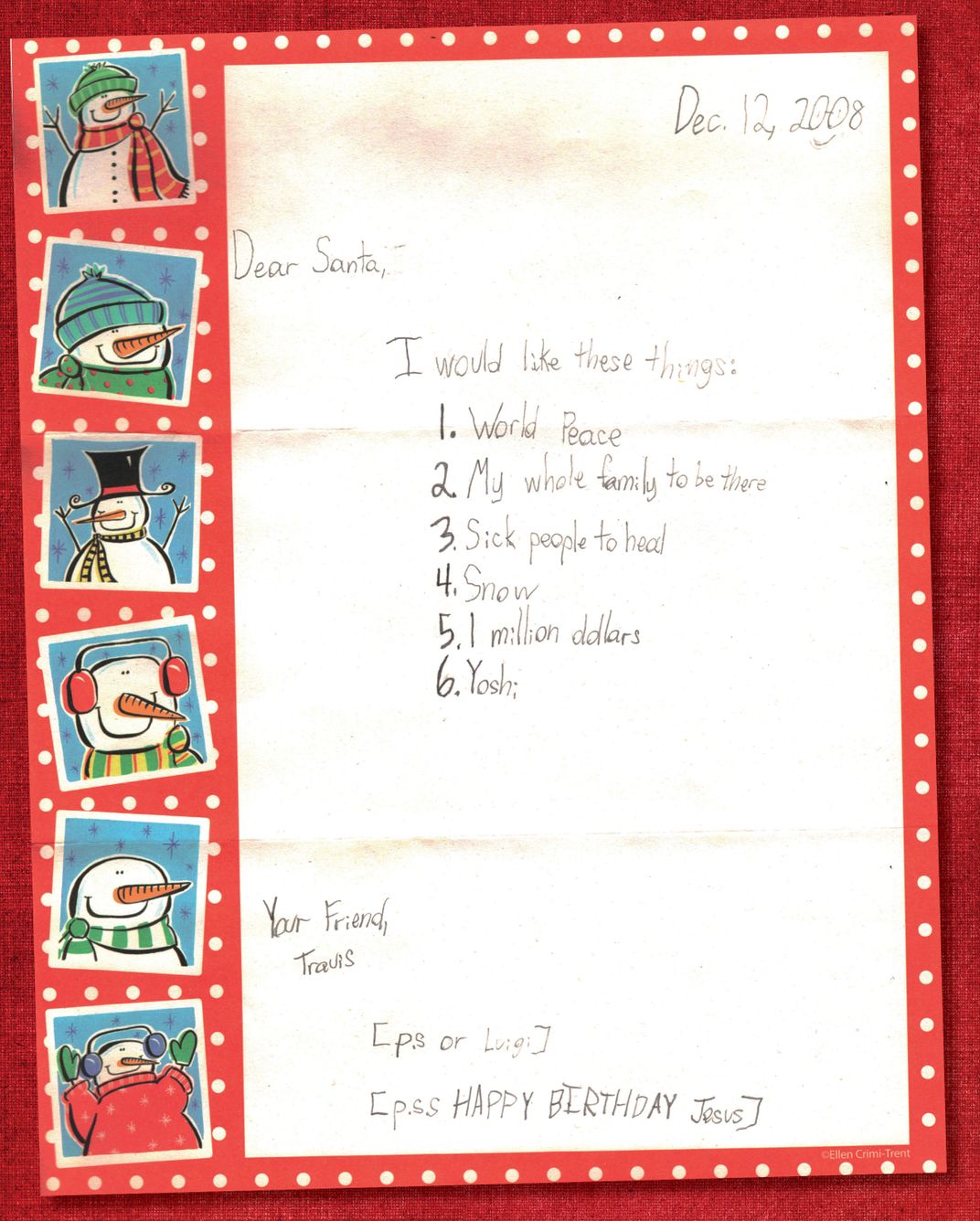

The letters reflect the changing wants of children, from spurs and a cowboy hat so the writer can “play Roy Rogers” to an Xbox with Assassins Creed 3, from a Shirley Temple doll to an American Girl doll. There are also some more unusual requests, such as a child in 1913 who asks Santa for a glass eye. One letter in Letters to Santa comes from an adult woman asking Santa to bring her a “tall, stately, well-bred…man of wealth with a steady income,” while in another, a boy negotiates with Santa to “trade you my sister when she comes from the stork for an elf.” A number of poorer children writing at the start of the 20th century even ask for coal—seeking warmth rather than viewing it as a punishment for naughtiness.

The letters tell a larger history as well. From World War I (a mother wrote to Gluck’s Santa Claus Association “We had to break up our home last winter, for my husband who is a longshoreman could not get work since the war began”) to the Great Depression; from 9/11 to Superstorm Sandy (a child writing in 2012 promises to “ask for much less this year so you can focus on the kids that are less fortunate than me”).

“I love the idea that we can see history through these letters,” says Thompson.

In more recent years, the process of answering Santa’s letters has been more regulated. In 2006, the Postmaster General formalized Operation Santa Claus nationally, putting in place a set of guidelines for all post offices taking part in the program. These include requiring donors to present a photo ID when they pick up Santa letters, and redacting the children’s full names and addresses—assigning each letter a number and storing the delivery info in a database that only the postal employees who actually deliver the gifts can access.

“It was different in every place it was done—some only had a letter-response campaign where they would send form letters out to the kids, there was no gift giving,” says Fontana. “In New York, we send only the gifts.”

It’s a much more modern approach to playing Santa than Fanny Longfellow or John Gluck could have imagined. Fontana hopes to see the program evolve further, scanning the letters and uploading them where people can fulfill children’s wishes from their laptop or smartphone. Programs such as EmailSanta.com and PackagefromSanta.com are already giving Santa the powerful tool of the Internet to help him accomplish his annual duties.

But what seems unlikely to change is kids’ continued eagerness to correspond with the jolly fellow, and adults’ continued enjoyment in playing him.

Alex Palmer will be discussing the history of Santa letters and signing copies of The Santa Claus Man at the National Postal Museum, on Saturday, December 12, from 3–5 p.m., as part of the annual holiday card workshop.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)