Celebrating Home Movie Day

Is there really no such thing as a boring or banal home movie?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111012123015SF_Filmmakers_470x251.jpg)

How important were home movies in your family? Since motion pictures were first marketed in the late19th century, they were available to home consumers as well as professionals. Pathé offered the specifically home-oriented 28mm filmstock in 1912, and by the 1930s, both 16mm and 8mm cameras had entered the home consumer market.

For the next two decades home movies were an expensive and at times demanding hobby. Miriam Bennett, whose delightful comedy A Study in Reds (1932) was selected for the National Film Registry, was the daughter of famous still photographer H.H. Bennett and helped run the family studio in Wisconsin Dells after his death. Wallace Kelly, an illustrator and photographer whose Our Day (1938) is also on the Registry, skipped lunch for a year to pay for a motion picture camera. Their work might better be called “amateur” rather than “home” movies.

But as Baby Boomers matured in the 1950s, and the cost of equipment and film stock dropped, home movies became a mainstay of family get-togethers. A grammar of home movies emerged as filmmakers focused on the same familiar tableaus. Children grouped around the Christmas tree, for example, or seated at a picnic table on the Fourth of July. Birthday parties, new cars, playing at the beach or by a lake, a big storm: home movies became a combination of the unusual and the everyday, with clothes and haircuts marking the passing of years.

Founded in 2002, Home Movie Day celebrates them all: the bizarre and the brilliant, the obscure and the famous. Formed as a sort of outreach effort for archivists, the annual affair gives everyone who attends the chance to screen their films. For a lot of family members without access to working projectors, this is a great opportunity to see what’s in their collection. At the same time, it lets archivists counsel on the need for preservation.

According to Brian Graney, a co-founder of Home Movie Day and the Center for Home Movies, a nonprofit organization that helps administer the project, the first event took place in 24 locations, almost all within the United States. This year Home Movie Day will take place in 66 sites across 13 countries on Saturday, October 15. (See the full list here.)

Graney, currently the Media Cataloger at Northeast Historic Film in Bucksport, Maine, wrote to me in an e-mail about the need to protect what can be extremely vulnerable films. “All home movies are at risk to some degree,” he explained, “because there’s no negative behind a home movie—the reel on the projector is the same one exposed in the camera. In commercial films you have multiple copies of the same content. Here, there’s just the one, and even for home movies held in archives, keeping that one safe might be the best we can do.”

According to Graney, “The greatest risk is in the widely held and wrongheaded idea that home movies are without interest to anyone but their creators, or that they’re all alike and all equally banal.”

Home Movie Day has helped bring some extraordinary films to a wider public, like Our Day and the Registry title Disneyland Dream (1956), a wonderful travelogue by the accomplished amateur filmmaker Robbins Barstow. Each year holds the potential for new discoveries.

Perhaps the best proof of the variety and scope of home movies can be found in Amateur Night: Home Movies from American Archives, an extraordinary feature produced and directed by Dwight Swanson. A compilation of 16 films dating back to 1915, Amateur Night provides an introduction to everything that is important about home movies, from personalities and historical events to sheer aesthetic pleasure.

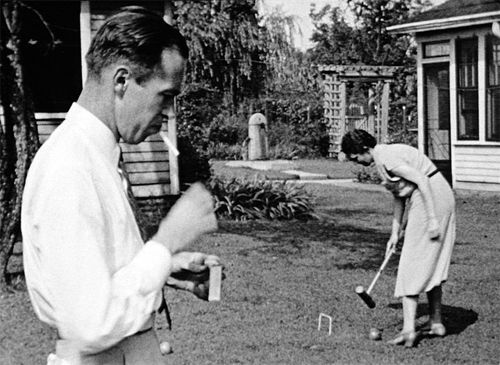

The celebrities in Amateur Night include director Alfred Hitchcock frolicking with his wife Alma Reville; the real-life Smokey Bear, shown recovering from burn wounds from a forest fire; and President Richard Nixon, mingling with crowds on an Idaho airport tarmac.

Other films in Amateur Night give us new approaches to incidents we think we may already know. For instance, Helen Hill’s Lower 9th Ward (2005, from the Harvard Film Archive) is a first-person account of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, filmed by someone who lived in and loved New Orleans. For me, Hill’s impassioned advocacy is more affecting than the reports of journalists trained to be objective about what they are covering.

Or take Atom Bomb (1953, from the Walter J. Brown Media Archives at the University of Georgia Libraries), filmed by Louis C. Harris, a journalist and later editor at Georgia’s Augusta Chronicle. Harris, who served in the 12th Air Service Command during World War II, was invited to Nevada to view the detonation of the 16-kiloton “Shot Annie” on March 17, 1953. His footage captures the awesome, terrifying effects of a nuclear blast in ways that more official accounts don’t.

“In the past two decades archives, scholars, and hopefully the general public, too, have started to develop a deeper understanding of home movies and amateur films,” Swanson wrote to me in an e-mail. “The curatorial philosophy behind Amateur Night is to show the range of diversity that has been found in the universe of amateur film, and to persuade people to think of them in new ways and not dismiss them as purely family records.”

For the past year, Swanson has been screening Amateur Night across the country. Sunday, October 16, he’s showing it in Los Angeles as part of the Academy Film Archive’s Home Movie Weekend. On Friday, November 4, he’ll be at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio. Do not miss the chance to attend a screening, because you won’t find Amateur Night on DVD. “There are no plans for DVD distribution,” Swanson said, “since we wanted it to be a film preservation project and to showcase the photochemical preservation work being done by preservation film labs such as Cineric, Inc.”

So drop into a local Home Movie Day event, and see Amateur Night if you can. As Swanson put it, “The goal is to show that there are some wonderful and amazing films found both in archives and in homes.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)