Celebrating Resistance

The curator of a portrait exhibition discusses how African Americans used photography to resist stereotypes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/curator-200802-388.jpg)

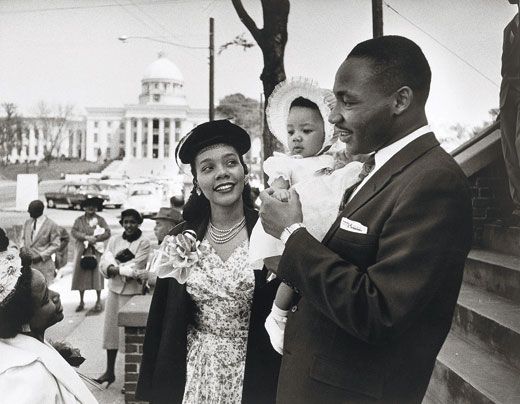

Photography scholar Deborah Willis is the guest curator of the exhibition, "Let Your Motto Be Resistance: African American Portraits," at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., through March 2. This is the inaugural exhibition of the recently established National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), which will open its own building on the Mall in 2015.

Deborah, how did you come to be the guest curator for this exhibit?

The director of the museum, Lonnie Bunch, called me and asked if I would be interested in curating a show, mainly because he is familiar with my work in photography and my interest in telling stories through photographs. Basically, I am a curator of photography and a photographer. I've written a number of books on images of black culture.

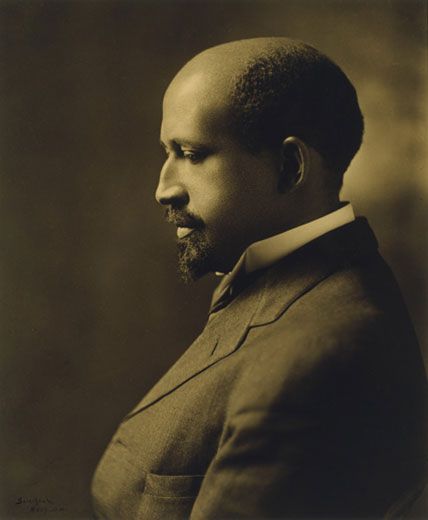

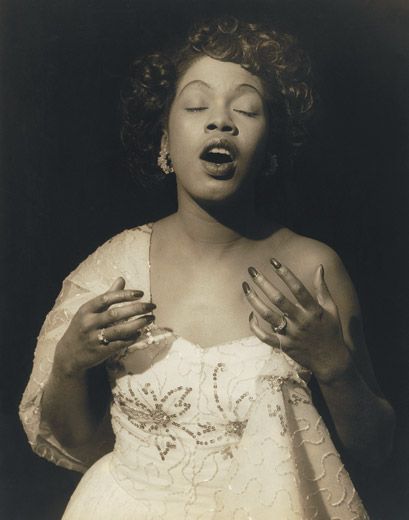

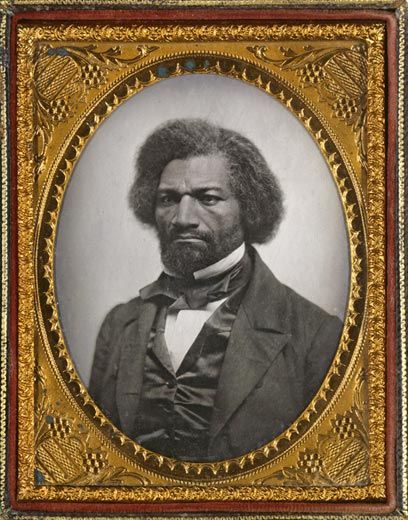

The images range from a 1856 ambrotype of Frederick Douglass to mid-20th century images of performers such as Dorothy Dandridge to a 2004 image of musician Wynton Marsalis. What is the connecting theme in these 100 portraits of Africans?

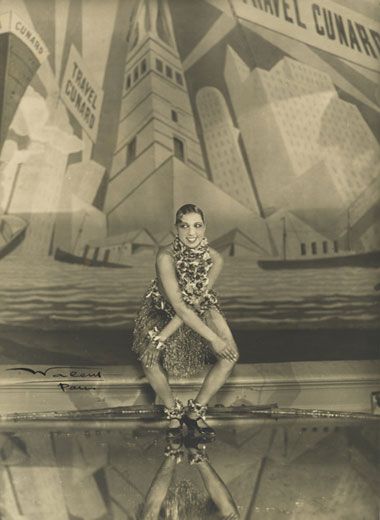

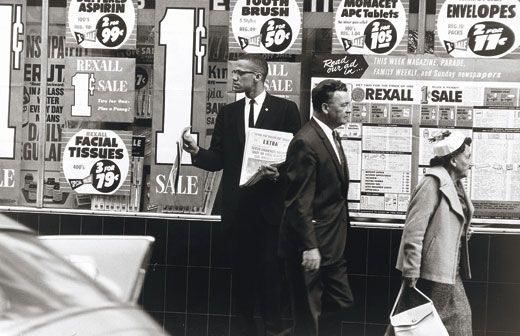

The whole concept is from the National Portrait Gallery collection. I was initially interested in how the gallery collected and what stories they presented through their collection effort of black materials. As I began to look at the portraits, I started to see a connection of how the different subjects posed for the camera, of how they performed for their particular fields. They knew their significance and contributed in the arts and in politics and they understood public space. I imagined the spaces of the times and then made the connection of what stories people conveyed throughout the portraits. Each one conveyed their self-importance and understood what they wanted to contribute.

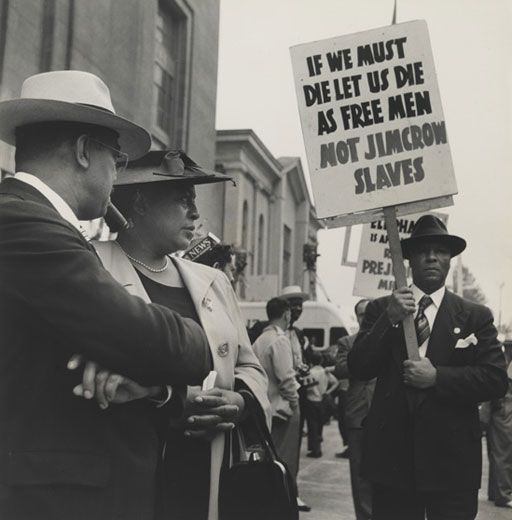

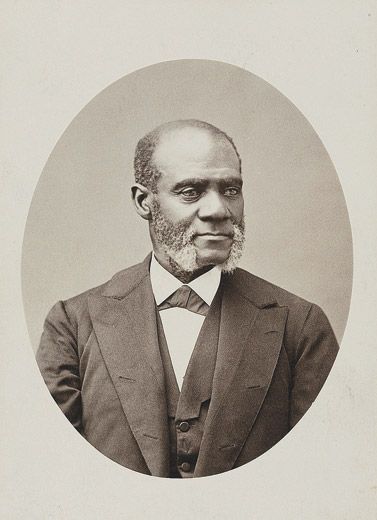

How did the quote by 19th-century activist Henry Highland Garnet become the inspiration for the title of the exhibit?

When I told Lonnie Bunch what I thought about the subjects in the portraits, their beauty and how they challenged the images that were circulating in the public at the time, the images celebrated their achievements and looked at dignity a different way, he said, "Oh, ‘Let your motto be Resistance! Resistance! RESISTANCE!'" He understood exactly what I saw in the image and that the notion of resistance could appear in a photograph, as well as in text. I had considered a different title for the exhibition. When I talked about the images I viewed and what I experienced, Lonnie Bunch came up with the title by understanding and underscoring the experience of resistance through the outside view of black subjects.

May I ask the title you originally considered?

Beauty and the Sublime in African American Portraits.

In your essay, "Constructing an Ideal," which appears in the exhibition catalogue, you quote Frederick Douglass as saying that "poets, prophets, reformers, all are picture-makers and this ability is the secret of their power and achievements." How did African Americans utilize the new medium of photography to construct an ideal?

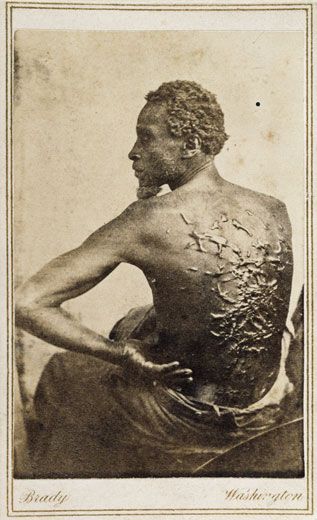

Black people in the late-19th century looked at photography as evidence of or a reflection of who they were. They preserved their image through this medium at a very important time because it was during and after slavery that some of these images were presented. Many African Americans thought it was important to preserve the images. They were a symbolic reference for them. Advertisements had black subjects as humorous or caricatures and black people wanted to use photographs to present themselves as they really were or as they imagined themselves or aspired to be.

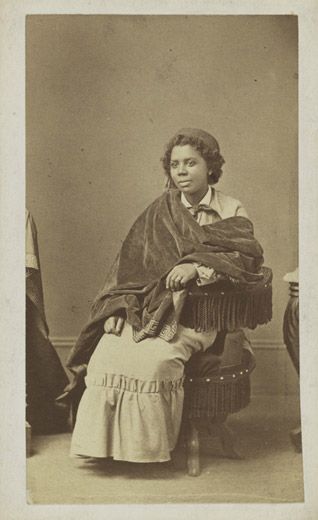

How were the 19th-century images of activists such as Sojourner Truth or artist Edmonia Lewis used?

Sojourner Truth had nine different portraits made because she knew as she lectured around the country that her photographic image was presented. She wanted the dignity of her presence to be remembered as a speaker and an orator. With Edmonia Lewis, she dressed in a way that was part of the art movement. The notion of bohemia, women wearing pants, wearing a tassel, her figure, she understood the creed of women and artists and I think she wanted to present that in her photograph.

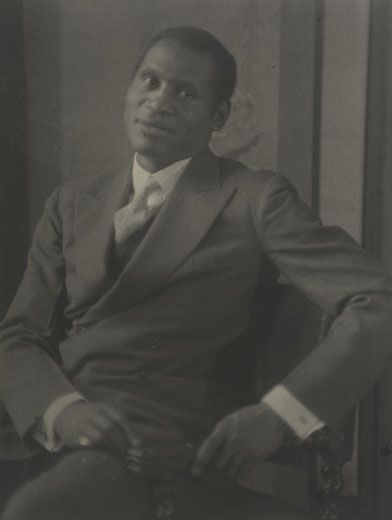

What role do you think that 20th century photographers such as Harlem's James VanDerZee and Washington, DC's Addison Scurlock played in reconstructing ideals?

They were not only reconstructing but constructing images that were modeled after their experiences, what it meant to have race pride, what it meant to be middle class, to see the beauty within their communities. They photographed the activities of the churches. They also understood beauty—beauty was an essential aspect—as well as the whole notion of communal pride. They were great studio photographers.

Communal portraits of pride are also discussed in the catalog. Can you provide us with one or two examples of communal portraits of pride?

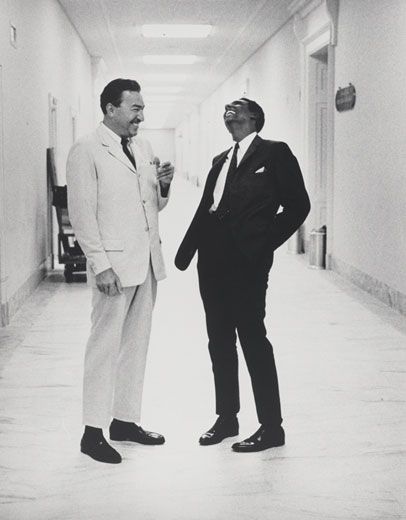

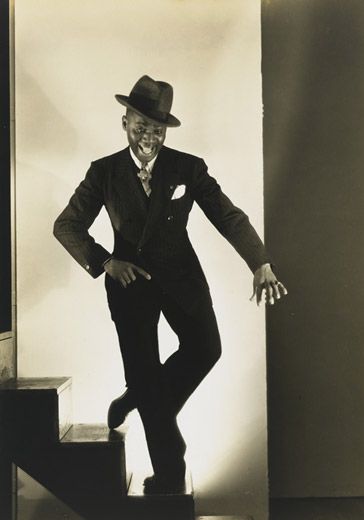

Well, one is the Abysinnian Baptist Church where Adam Clayton Powell Sr is standing outside. The church earned its mortgage within a five-year period. It shows a beautiful edifice of a church but also shows the large Sunday school community, so there was a sense of community pride through ownership. That was one photograph that looks at community pride. In terms of a personal experience, look at the photograph of Nat King Cole. There is an open sense as he walks on stage. The people in the audience are actors and entertainers also, but they are looking at him with pride as they applaud. That's another aspect of it too, not only with the black community but with the white subjects who are looking at him. They see his dignity, his manhood, his stylish dress.

Photographer Gordon Parks said that a photographer must know the relationship of a subject to his era. Are there a couple of images that demonstrate that concept especially well to you?

The photograph of Lorraine Hansberry [author of "A Raisin in the Sun"], where she's standing in her studio. She has an award she's received. We also see a blown up photograph someone has made of her, this whole notion of her positive experience of living in an environment of self-pride became an affirmation of what she contributed to literature, to the stage.

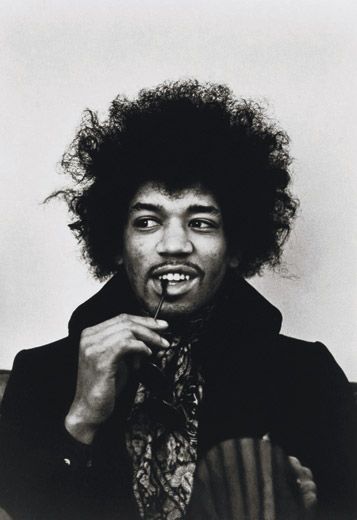

If the idea of resistance is the main theme of the show, are there other subthemes?

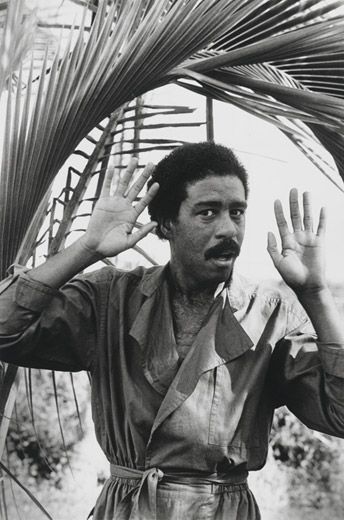

Resistance and beauty are essential to it. There is the photograph of Jack Johnson. He understands power; this is a black man at the turn of the century with his shirt off. [We see] the body, the gesture of power that he makes with his fist. So subthemes within there are power and beauty.

Did you look for any particular criteria as you decided which photographs to include?

No, I didn't have any. There were just experiences I had as I looked at the images. I didn't have any critical way of looking. There was a story that I wanted to tell that just spoke to me quietly. There are those curatorial moments when you know something links as an idea, as you see the images, the idea becomes tangible.

Can you name your favorite photographer or the image that resonated most for you?

There is a photograph of Jackie Robinson where he's seated in his study, and he's balancing a ball, he's throwing a ball up. That photograph says so much as a metaphor about his life—that he's well balanced. The photograph shows books over his head. The stereotype of an athlete is not as an academic or someone well read but he balances all that the way Garry Winogrand made that photograph.

I've read that a lot of the subjects weren't famous when their photographs were taken.

Rosa Parks was at the Highlander Folk School learning how to become an activist. The Supremes were about to start off at that time, and photographer Bruce Davidson was in the dressing room of the Apollo Theater. You see three women who were about to begin their dream of singing at the Apollo Theater.

When you consider the century and a half of photography displayed in the exhibition, what do you believe are the most important ways in which the role of photography has changed?

I think it's more popular; photography is an affirmation more and more. I don't think that the role of photography has changed but that people are affirming themselves, their presence in society. Portraits are made with hand held cameras, as well as with the phone. Everyone's taking portraits now, so it's a sense of affirmation.

After you made your selections and walked through the exhibit, what did you feel?

That the link worked. Sometimes you work in a vacuum and you're not talking to anyone and sometimes you wonder if it's real. So, the whole experience of subliminal messages is why I wanted to have the notion of the sublime in the photographic portraits. I see that it's a way of telling that story, that it reinforced what I'd been thinking and had not been able to visualize in a collective.

What does it say about America to you?

I see it as not just about America but about life, the whole range of experiences, all of the subjects have effected an international audience, as well as a local communities, as well as a national audience, so they're all linked. But there is a powerful voice for each person that follows us throughout. The world has been affected by a minimum of 5 to 10 people through sports, music, writing, art, etc., so there is an international experience with all.

And what are you tackling next, Deborah?

I'm working on a book called Posing Beauty. I'm still trying to get my beauty out there. So I'm looking at how, in using photography within the black communities, people have posed beauty from 1895 to the present. 1895 is a moment from the New Negro Period right after slavery and [I examine] this new experience of how blacks perceived themselves and how beauty contests became important during that time. I'm finding images of beauty through a range of experiences from the photographer's point of view, from the way people dressed going to the studio to how beauty is coordinated as a political stance, as well as an aesthetic. Norton is publishing it.

The portraits from the exhibition, "Let Your Motto Be Resistance," as well as a number of essays by Willis and other scholars, are contained in a catalog by the same title, published by Smithsonian Books and distributed by HarperCollins. A scaled-down version of the exhibition will begin touring select cities around the country in June.