Nippon Budokan, in Tokyo, is a revered center for budo, or Japanese martial arts. Steps away from some of the busiest avenues of the hyperkinetic city, a pedestrian road leads past the stone fortress walls and tree-lined moats of the Imperial Palace into the forests of Kitanomaru Park, a natural refuge first landscaped for the shoguns in the 17th century and only opened to the public in 1969. There, the Budokan, built for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, hovers over the foliage like a postmodern pagoda: It was modeled on one of Japan’s most ancient and beloved Buddhist temples, the Hall of Dreams, and its octagonal roof, whose shape is intended to echo Mount Fuji, is topped with a golden onion-shaped giboshi, a traditional ornament believed to ward off evil spirits. But on a pre-Covid visit, the serenity dissolves the moment you enter the portals during a karate tournament. The corridors are teeming with sweaty karateka, or practitioners, in white uniforms and colored belts, while the cavernous arena resounds with the roar of some 10,000 spectators, cheering on six competitors as they spar simultaneously in three courts below enormous video screens, their dancelike steps mixed with the familiar kicking, punching and chopping.

It’s in this stadium that karate is set to debut this summer as an Olympic sport. In early August, 80 finalists, half men and half women, will face off in two competitions in kata, ritualized solo exercises, and six competitions in kumite, the sparring that is more familiar to foreign audiences. Although karate is not on the schedule for the Paris Games in 2024, the moment is still a significant breakthrough for the sport’s estimated 100 million international practitioners. And there is certainly a pleasing symmetry to having karate debut at the Tokyo Games, in the same arena where the first World Karate Championship was held in 1970.

But it’s also an opportunity to consider the surprising historical nuances of the martial art. Though people outside Japan tend to regard karate as quintessentially Japanese as sushi or cherry blossoms—a seemingly timeless practice whose traditions are shrouded in Zen mysticism—many of karate’s most recognizable elements, including the uniforms and the hierarchy of expertise designated by colored belts, are not ancient but arose in the 1920s. Japan officially recognized karate as a martial art only 86 years ago. And its origins are not in mainland Japan at all: It was born in the archipelago of Okinawa, a long-independent kingdom whose culture was heavily influenced by China and which maintains its own identity today.

In fact, it was karate’s lack of nationwide popularity in Japan that allowed it to flourish after the Second World War, evading the demilitarization program imposed by the Allied occupying forces that suppressed other ancient combat arts.

* * *

Karate’s long journey to international stardom is believed to have begun in the 1300s, when the first practitioners of Chinese martial arts made their way to Okinawa, an enclave of subtropical islands ringed by white sand beaches located some 400 miles south of mainland Japan, 500 miles from Shanghai, and 770 miles from Seoul. The archipelago was soon known as the Ryukyu Kingdom, with its own language, dress, cuisine and religious ceremonies. Its deep cultural ties to the mainland were maintained even after 1609, when samurai invading from Japan turned Ryukyu into a puppet state. Okinawans were forbidden to carry swords, so underground groups of young male aristocrats formed to refine unarmed varieties of combat as a secret resistance, blending local and Chinese styles, and sometimes, according to local legend, using farming implements like scythes and staffs as weapons. (Versions are still used in karate, with the rice flail becoming the nunchaku, or nunchuks, for example.)

This hybrid martial art became known as kara-te, “Chinese hand.” There were no uniforms or colored belts, no ranking system and no standard style or curriculum. Training focused on self-discipline. Although karate could be lethal, teachers emphasized restraint and avoiding confrontation. This peaceful principle would later be codified as the dictum “no first strike.”

“Okinawan karate has never been about beating your opponent or winning victory,” says Miguel Da Luz, an official at the Okinawa Karate Information Center, which opened in 2017 to promote the local origins of the art. “It focuses on personal development and improvement of character. This reflects the personality of the Okinawan people. The island mentality has always been about being diplomatic rather than aggressive to resolve disputes.”

Any illusion of Okinawa’s independence ended during the cataclysmic era of change that came after 1868, when Japan embarked on a breakneck industrialization program, creating a modern army and navy. With a new taste for imperialism, Tokyo dissolved the old kingdom of Ryukyu in 1879 and set out to effectively colonize the archipelago, repressing its traditions and imposing Japanese culture through schools and conscription. Most Okinawan karate masters bowed to the inevitable and brought their martial art more into the open, introducing it into the island school system and volunteering for military duty themselves.

“The upper middle classes of Okinawa saw assimilation with Japan as the future,” says Dennis Frost, director of East Asian studies at Kalamazoo College and author of Seeing Stars: Sports Celebrity, Identity, and Body Culture in Modern Japan. “Karate had been very amorphous, so it could be tweaked and introduced to new audiences.”

At first, the alien style made only modest inroads in then-xenophobic Japan. Interest was piqued in the early 1900s, when doctors examining Okinawan candidates for military service noticed that karate practitioners were in far better physical condition, and stories began to filter around the mainland. One Okinawan karate master of royal lineage, Choki Motobu, gained celebrity status in Osaka when he attended an exhibitions bout between a European boxer and Japanese judo experts. He became so frustrated by the boxer’s victories that he jumped into the ring, challenged the foreigner and knocked him out with a single blow. In 1921, Crown Prince Hirohito, soon to be emperor, visited Okinawa and was impressed by a high school karate demonstration in the ancient Shurijo Castle.

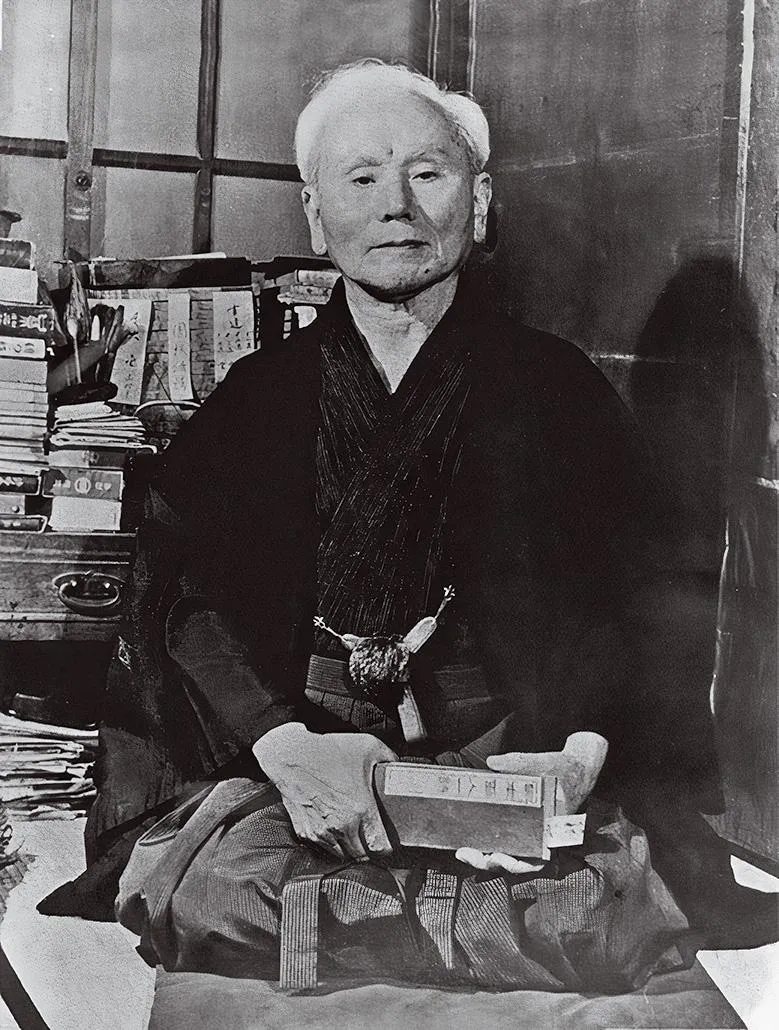

The next year, the Japanese Ministry of Education invited an Okinawan master named Gichin Funakoshi to demonstrate karate at an exhibition in Tokyo. A quiet, middle-aged schoolteacher, poet and student of the Confucian classics with a fondness for calligraphy, Funakoshi was an unlikely proselytizer. But his display impressed the Japanese government officials and judo masters, and he decided to stay and teach karate on the mainland. It was a hard road at first: He lived hand-to-mouth for several years and worked as a janitor. Most Japanese, in the words of one author, regarded karate with condescension and suspicion as “a pagan and savage art.” But with self-denying zeal and creative changes, Funakoshi began targeting university students and white-collar office workers, who were more open-minded and receptive, and won over converts. In 1935, Dai Nippon Butoku Kai, the budo establishment that oversaw traditional Japanese martial arts, including sumo wrestling and kendo (a type of samurai-style fencing with bamboo sticks), formally accepted karate.

But the victory also changed karate forever. The ultranationalistic mood of the 1930s influenced all aspects of culture. To make the imported style more familiar and palatable, Funakoshi and his followers adopted the trappings of judo, including the training uniforms, colored belts and rankings. Its Chinese origins were particularly suspect, as tensions between Asia’s two great empires increased and the prospect of full-scale war loomed. In 1933, the written symbol for karate in Japanese was changed to a homophone—that is, a word pronounced the same way but with a different meaning. Instead of “Chinese hand,” karate was now “empty hand.” “It’s a fascinating example of what historians call ‘invented tradition,’” says Frost. “Many elements we think of as essential to karate today were actually added just a century ago.” Even so, he says, karate remained one of the lesser martial arts in Japan. To classical purists, it kept a faint whiff of the foreign, even a slightly thuggish air.

This outsider status turned out to be the secret to karate’s next phase, as a runaway global success after the Second World War. One of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s first acts during the Allied occupation of Japan in 1945 was to impose a sweeping ban on military education and drills, which effectively closed down all martial arts—except karate. “Budo was seen as the reservoir of the Japanese military and warrior spirit,” says Raúl Sánchez-García, a lecturer on the social sciences at the Polytechnic University in Madrid, and author of The Historical Sociology of Japanese Martial Arts. The practice had been used to inculcate the ancient samurai values of blind loyalty, self-sacrifice and total refusal to surrender in the armed forces, forming the ideological basis of wartime banzai charges, kamikaze attacks and seppuku, ritual suicides, as well as the contempt Japanese officers showed to prisoners of war. “But karate was regarded as peripheral, a recent import, and more like calisthenics and not attached to the samurai tradition,” Sánchez-García says. As a result, it became the only martial art openly practiced from 1945 to 1948, when tens of thousands of American G.I.s—with plenty of spare time guarding the placid Japanese population—became exposed to it. “American servicemen had a genuine fascination with karate,” Sánchez-García notes. “It was studied and taught on U.S. military bases.” In perhaps the biggest change, tournaments were promoted to make karate resemble a “democratic” sport in the Western sense, with winners and losers.

Funakoshi’s students continued training after the dojo was lost in the Allied firebombing, and in 1949 formed the pioneer Japan Karate Association (JKA). The revered “father of modern karate” died in 1957 at age 88, leaving his style, Shotokan, to flourish as the most popular today. Japanese devotees make the pilgrimage to Funakoshi’s shrine in the Engakuji Temple, a complex of pagodas on a leafy mountainside near the coast an hour by train south of Tokyo. But even at the time of his death, karate was on a trajectory that would see the art evolve once again.

* * *

The Western fascination with Japanese unarmed combat goes back to the moment in 1868 when the country, closed to outside contact for more than 250 years, first opened its doors and allowed foreign visitors to experience its culture firsthand. In 1903, the fictional Sherlock Holmes managed to escape a death plunge with Moriarty thanks to his skill at “baritsu” (a misspelling of bartitsu, an Edwardian British style that mixed boxing and jujitsu), while Teddy Roosevelt trained in judo at the White House in 1904 and sang the sport’s praises. But the convergence of events after the Second World War saw karate become an international phenomenon.

As far as sports scholars can discern, the first returning G.I. to bring karate to the United States was a 21-year-old middleweight boxing champion named Robert Trias, who had been stationed in the Pacific as a naval officer. According to Trias (in a cinematic account in the magazine Black Belt), he was constantly asked to spar by a frail-looking Chinese Buddhist missionary named Tung Gee Hsing. When Trias finally relented, the “tiny little guy” gave him, he recalled, “the biggest thrashing of my life.” Intrigued, Trias studied to become one of the West’s first black belts, and returned to Phoenix, Arizona, in 1946 to open America’s first karate dojo, with an emphasis on the martial art as a form of self-defense. He was soon presiding over nearly 350 clubs as head of the U.S. Karate Association. He worked as a highway patrolman, penned the first karate textbooks in English, and organized the first world championship, in 1963.

Over the coming years, karate’s “tradition” was reinvented a second time. The martial art had been transplanted to the U.S. and Europe with very little cultural context, and the stories that thrived about its past were often as realistic as cowboy legends in the Wild West. “There are Western fantasies about every martial art,” explains Sánchez-García. “Karate is laden with mysticism and stories about secret cults, which are part of the stereotypical vision of ‘the Oriental.’ Films, in particular, spin fantasies of superhuman heroes, an 80-year-old man who can defeat ten assailants with his bare hands.” Karate became overlaid with spiritual elements that could supposedly be traced back to darkest antiquity.

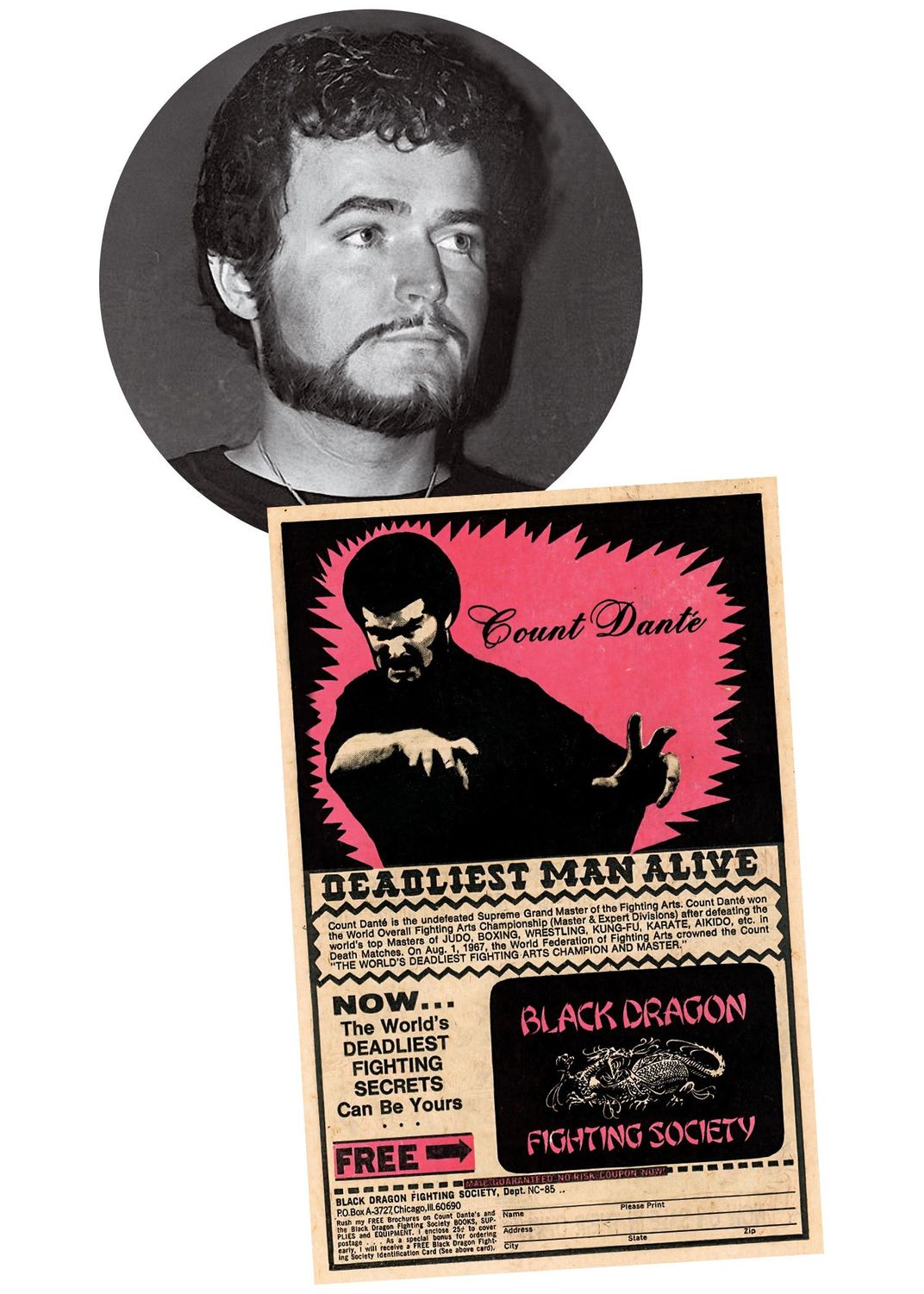

Trias shared one story that karate had been born in a monastery in China, where a wandering Indian master named Bodhidharma noticed that sedentary monks were growing sickly and devised the martial art to cultivate their strength. Another fable involved the origin of black belts: It was said that all practitioners once started with white belts but never washed them, so the darkening color reflected the owner’s experience. One of the most imaginative American teachers was Trias’ pupil John Keehan, a Chicago-based black belt who styled himself “The Deadliest Man Alive” and the “Crown Prince of Death.” Keehan was another oddball: In the 1960s, he ran karate schools, sold used cars and worked at sex shops, while moonlighting as a hairdresser for Playboy. Taking a royal title from Spain, he began to call himself “Count Juan Raphael Dante,” but also claimed membership in a secret cult called the Black Dragon Fighting Society, which had taught him to deliver “the death touch.” Stories spread of karate black belt holders having to register their hands and feet as deadly weapons.

Such fanciful visions were transmitted to huge audiences through Bruce Lee movies of the early 1970s and The Karate Kid (1984). “By the mid-’80s, you had lineups around the street at American dojos,” says Ryan Hayashi, a Japanese-trained instructor in Germany with an international YouTube following for his classes. “Teachers were like rock stars. But people didn’t really know the difference between karate, taekwondo or kung fu.” (In broad terms, taekwondo originated in Korea and involves more kicking than karate. Kung fu originated in China and is an umbrella term for a number of disciplines; as a martial art, some of these disciplines have movements that are more graceful, while karate is often more “linear” and direct.)

* * *

Karate is now a multibillion-dollar world industry, with dojos in urban malls from Sydney to Paris and an enormous market for equipment and classes. And its popularity shows no sign of slowing. Within the U.S., it has tapped into a deep contemporary need, some scholars suggest. According to anthropologist John J. Donohue, the exotic narratives, ritual performances and physical self-discipline inherent to martial arts training may help generate a sense of purpose and the illusion of control in a modern world that can often seem hostile and spinning out of control. Mark Tomé, who runs a karate dojo in downtown Manhattan called Evolutionary Martial Arts, sees a broader appeal. “A large part of the American population admires Eastern philosophy, religion and culture in all its forms-—everything from meditation to yoga and Japanese manga comics and anime films,” he says. “Karate makes people feel different, that they stand out.”

The ongoing Western emphasis on karate as a practical form of self-defense is quite different from what Mathew Thompson, a U.S.-born professor of Japanese literature at Sophia University in Tokyo, has experienced while studying the discipline for nine years in Japan. “From what I have seen, karate is very low-key here,” he says. “There’s no illusion, or even a fiction, that karate is supposed to protect you or hurt anybody else. People talk about it in a very different way. There is no sense of machismo.” Instead, he recalls one training session where students did nothing but punch the air 1,300 times. “The repetitive motion was a way of perfecting the most efficient movements,” he recalls. “You wouldn’t do that in the U.S.”

Because of karate’s mass popularity, it’s surprising it has taken so long for it to reach the Olympics, while judo has been on the roster since 1964. One reason is that karate, for all its individual discipline, has been subject to endless infighting, with no uniformly recognized governing body. The original JKA, created by Funakoshi and his students after World War II, splintered in the 1990s with a series of legal struggles with rival groups that ended up in the Japanese Supreme Court. Even the body now recognized by the International Olympic Committee, the World Karate Federation (WKF), does not command universal support.

The divisions reflect the sport’s flexible nature. There are four main styles of karate from mainland Japan, including Funakoshi’s version, Shotokan, but the reality is far more kaleidoscopic. Literally hundreds of versions exist. Regular schisms continue, and almost every teacher adds his or her own personal flourish. Meanwhile, back in karate’s birthplace, the Okinawa Islands, patriotic practitioners deride all mainland styles as inauthentic. The sport’s approval for the Olympics prompted a provincial government campaign to have its true origins recognized: In 2017, the state funded the building of the Karate Kaikan (“meeting place”) inside a ruined castle in the city of Tomigusuku to promote the local brand, an extensive white complex with cavernous competition halls, historical exhibits and the information center. Karate workshops are now booming across the archipelago, with some 400 dojos that promote the “correct” local style, which still emphasizes the more spiritual side of the art, while tour operators take foreign visitors to monuments to old Okinawan masters and quirky shrines, such as a cave where a shipwrecked Chinese sailor (and legendary martial arts practitioner) supposedly took refuge centuries ago.

Meanwhile, the Olympics are giving a boost to karate’s popularity on the mainland, where enrollment in the art had been waning, with Japanese schoolchildren more attracted to judo and kendo, or lured to Western sports like soccer and baseball. “Karate suffered from a bad reputation, with the chance of injury seen as very high,” says Thompson. “Parents and grandparents did not want their kids involved.” Until the 1990s, tournaments had virtually no rules and could be brutal, he explains, adding that one teacher he met in Tokyo had lost most of his teeth. “The Olympics has changed that. Karate has become much more mainstream and international.” The WKF devised regulations for Olympic contests that limit the chance of injury and make them easier for audiences to follow, such as refining the point scoring system and restricting the use of excessive force: attacks to vulnerable body areas like the throat and groin, open palm strikes on the face or dangerous throwing techniques. In the pre-pandemic lead-up to the Olympics, karate exhibitions were held in the Tokyo Stock Exchange and shopping malls. Not everyone is happy: Online chat rooms are filled with practitioners who want more body contact, others demanding more flexibility in competitions. Some find the kata too “showy,” or object that the point-scoring process was simplified only to make it more “audience-friendly” and comprehensible for Western TV viewers. “There is concern that once rules have been codified for the Olympics, we won’t be able to change them again,” says Thompson. “Karate will be more like judo, it will lose something.”

Finally, hard-line traditionalists have a more philosophical objection to karate in the Olympics. The unabashed quest for personal glory that marks the modern Games is a betrayal of karate’s true spirit, they argue. Many Japanese teachers bristle at the idea of calling karate a “sport” at all. “In a Western-style sport, the aim is gaining victory at all costs,” says Thompson. “In Japan, even when you’re sparring, karate is not just about gaining a point—it’s about how you do it.” It is a cultural difference, he adds: “In Western sports, it’s OK to cheer when you win, to appeal to the audience, punch your arm. In karate, that is strictly forbidden. You would be immediately disqualified! You have to show respect for your opponent at all times.”

“True karate is about competing with yourself, not with other people,” agrees Da Luz of the Okinawa Karate Information Center. This also makes it a lifetime practice: “Tournaments are not a bad thing for young people. It’s an experience. But you can’t do it all your life. In Okinawa, many karate masters continue into their 80s. It’s not a sport but a part of our culture, like dance or playing the three-stringed lute.” The Germany-based trainer Ryan Hayashi says, “Karate feels like attending a wedding or being an altar boy. Tradition flows through you.” By focusing on competition, he suggests, “karate runs the risk of losing its soul.”

Despite the infighting, eight American hopefuls have been training in their home cities across the United States for the Tokyo Olympics throughout the pandemic, three in Dallas and others separately. While the solitary, ritualized kata moves have been easy to practice under Covid, the two-person sparring of kumite has been curtailed by the mosaic of local restrictions on contact sports, with Texas, for example, being more relaxed than New York. Significantly, karate practitioners qualify as individuals rather than as group national teams. “It’s been tough,” says Phil Hampel, chief executive officer of the USA National Karate-do Federation, the governing body for sport karate in the United States. But under the complicated qualifying process, one U.S. competitor, Sakura Kokumai, was confirmed in late May, while several others are contending for spots on the team, as this magazine goes to press.

* * *

Like other practitioners, Hampel was delighted karate was approved for Tokyo, and he feels that its “foreign” origins are only a historical curiosity for its millions of fans around the world. Still, karate was not approved for the Paris 2024 Summer Olympics, despite its popularity in France.

“Everyone [in the karate community] was disappointed,” Hampel says of the 2024 decision, particularly because karate has in recent Pan American Games proven to be the most popular combat sport for international TV broadcast; he hopes there will be enough world interest in karate’s Tokyo debut for it to return to the Los Angeles Olympics in 2028. “The current rules will ensure plenty of action and energy for viewers,” he says.

Such a media-driven return is far from impossible, says Kit McConnell, the IOC sports director based in Lausanne, Switzerland: “Being in the Olympics is an amazing stage for karate. Not only will it give access to its tens of millions of supporters, it also reaches a wider audience of those unfamiliar with it, which will build up its fan base and bring in new people. We’re hugely excited about karate being in Tokyo.”

It would be the final irony for a discipline that was born centuries ago in strict secrecy to reach its next level as a mass spectator sport.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/a4/36a4e18b-e200-450d-851b-1914b38546f7/mobile_opener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e7/e3/e7e3f814-32ab-490a-98fd-ede0f8c887a4/karateopener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)