Chainmail, Metal Spikes and Unbreakable Material: Can We Design a ‘Shark-Proof’ Wetsuit?

For years, inventors have tried to create a wetsuit capable of withstanding a shark’s deadly bite

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130809013037sharkproof-wetsuit-thumb.jpg)

It’s tough to believe, but shark cage diving is quite safe. Yes, the idea of hanging off the side of a boat to come face-to-face with a great white shark sounds like a death wish. But people who participate in the extreme activity are enclosed in a galvanized steel cage built to withstand the bite of massive, toothy predators. When sharks approach, lured by bait tossed overboard by tour operators, divers can observe the creatures through a viewing gap less than a foot high. This ethically ambiguous practice, known as chumming, risks teaching sharks to associate food with the presence of humans. So far, though, no human deaths associated with shark cage diving have been reported.

But what happens if a shark lunges into the cage through that little gap? While a pair of terrified divers managed to escape such an ordeal unharmed earlier this year, the outcome could have been a lot worse. Unlike cages made of steel, wetsuits made of neoprene and nylon don’t stand a chance against a great white’s deadly bite. Thankfully, your chances of being killed by a shark are incredibly small: one in 3.8 million, worse odds than your chance of being struck by lightning.

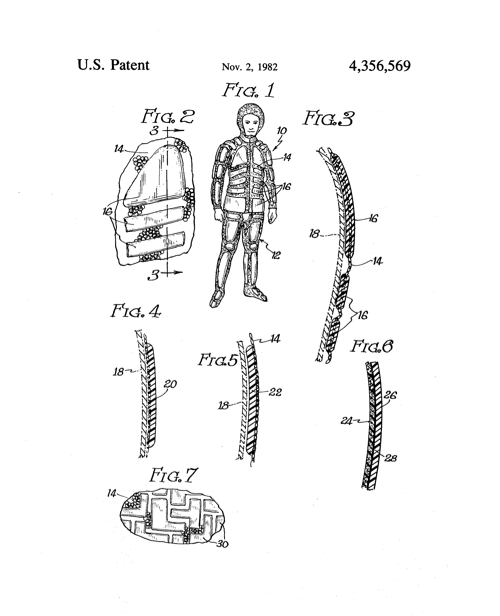

Still, that hasn’t stopped inventors from dreaming up aquatic garb that will protect swimmers, surfers and others. In 1980, marine biologist Jeremiah S. Sullivan filed a patent with the United States Patent and Trademark Office for an armored wetsuit, built to protect divers from shark bites. Here’s what it looked like:

Sullivan wrote that sharks like to test the surface of potential prey before biting down. “If the shark’s teeth strike a hard surface, particularly a hard metal surface, the shark will ordinarily back off,” he explained in the patent, which was issued two years later. “Although suits of armor and license plates have been found in the stomachs of sharks, the creature actually prefers meals that are softer and easier to chew.”

Sullivan’s wetsuit is made of chainmail or steel mesh. Plates made of tough plastic material are embedded into the suit in spots away from joints, to preserve the wearer’s mobility. The complete suit resembles a “tough, hard, lobster-like exterior shell.” The steel mesh deters curious sharks from biting down, and prevents, to an extent, their razor-sharp teeth from cutting into the wearer’s flesh if they do.

A similar design is used today by Neptunic, a company that specializes in stainless steel and titanium “sharksuits” meant to reduce injury from shark bites. The company’s demographic isn’t your average swimmer though. The $5,000 stainless steel and $25,000 titanium suits are used most often by aquarium workers and underwater photographers and camera operators. The suit has been tested with a range of shark species, says Neptunic president Neil Andrea, who says he’s been bitten dozens of times while wearing it and didn’t get hurt. When it comes to great whites, though, your chances aren’t good. “There’s just nothing out there right now that can stop the bite a great white can put down,” he says.

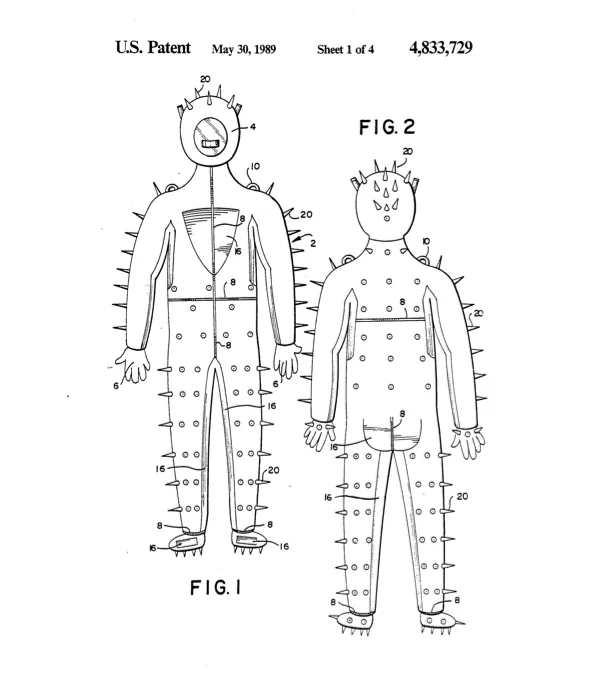

That’s because a shark bite, as we might expect, packs more than just a punch: an 8-foot-long great white shark can exert 360 pounds of force in one chomp. But knowledge of this power hasn’t deterred the inventors who want to subdue it. A few years after Sullivan filed his patent, Nelson and Rosetta Fox filed their own for a “shark protector suit.” The rubber suit, complete with a helmet, face mask and gloves, is covered in spikes. Like Sullivan, the Foxes suggested covering the suit in rigid plates for further protection, should a shark overcome the sharp metal spikes.

The problem with such a suit, of course, is the risk the spikes pose to the wearer himself. The patent doesn’t mention if the sharp features could pierce the material of the suit, but even if they couldn’t, how would you feel about turning into a human flail? That, and you’d risk seriously injuring shark and other fish around you.

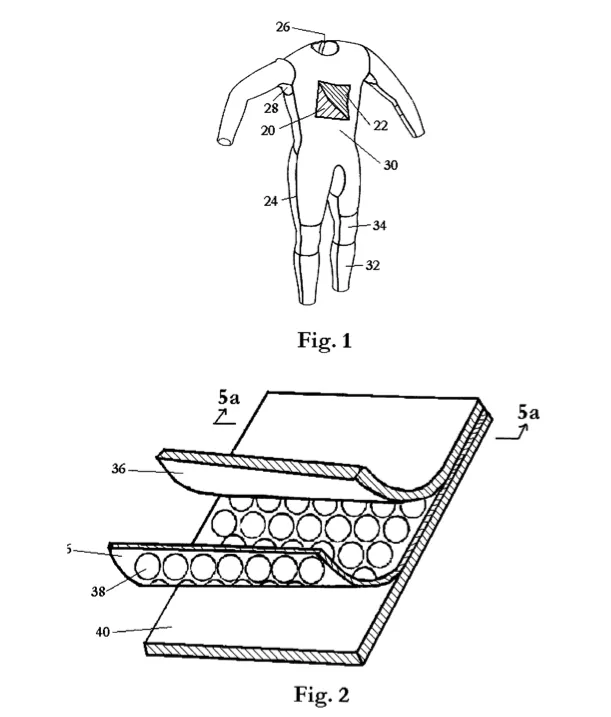

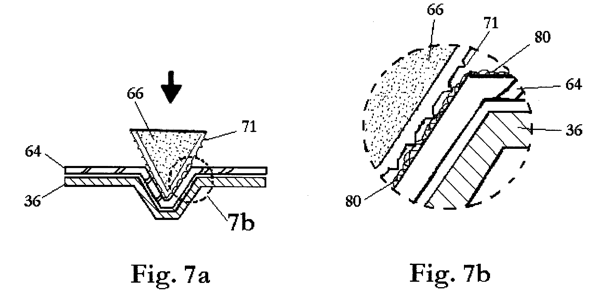

By the 21st century, John Sundnes saw that the answer to developing a “shark-proof” wetsuit didn’t involve boarding up the bodies of swimmers. Rather, protection could start with the wetsuit’s material itself. Filed in December 2006, Sundnes’ patent was for a puncture-resistant, lightweight and form-fitting wetsuit aimed at ocean sports enthusiasts.

The material is made of a layer of high-strength, laminated fiber material, heat and pressure-fused between two layers of elastic material, such as nylon or neoprene. Nylon helps to reduce the body’s natural drag as swimmers or divers move through the water, while neoprene creates warmth by capturing water between the suit and skin.

The patent’s drawings include a depiction of a shark tooth making contact with the material. As the tooth pierces the wetsuit, Sundnes writes, the flexible material yields to the form of the tooth, theoretically diluting the severity of the bite. Watch Sundnes test the strength of the material against a model shark jaw here. While the material appears to fare well against the fake jaw, a human being obviously can’t exert the same amount of force as a shark’s maw could. What’s more, all bites are not created equal. They can range from small but painful nibbles to lethal chomps. If a shark gets a hold of its prey and starts shaking it around, its victim is feeling more than just the animal’s teeth, but the pull of hundreds of pounds of muscle too.

The problem with designing a shark-proof wetsuit appears to lie in striking a balance. Too many protective elements, like rigid plastic plates or all-over steel mesh, and the wearer can only move slowly. Not enough and sustaining injury from a shark bite is practically inevitable, no matter how quickly the wearer can maneuver out of harm’s way.

Perhaps the secret to shark-proofing a wetsuit involves eliminating the potential of a shark attack altogether. Last month, Australian scientists, working with a design company, unveiled two kinds of wetsuits that protect wearers by tricking how sharks see them. In the case of “Elude,” they don’t see them at all—the suit’s pale blue and white pattern takes advantage of sharks’ colorblindness, rendering the wearer invisible to the shark’s eye. “Diverter” is covered in black and white stripes, a pattern that mimics signals in nature that tell the shark the swimmer isn’t tasty. Both suits are made of standard, lightweight material, so they’re aimed at surfers. The smart design achieves something previous ones haven’t been able to: It doesn’t force the wearer to choose between comfort and protection.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)