Charles McIlvaine, Pioneer of American Mycophagy

“I take no man’s word for the qualities of a toadstool,” said the man who took it upon himself to sample more than 600 species

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120208013026oyster-mushroom-mycology.jpg)

In 1881, Charles McIlvaine, a veteran of service to the Union in the Civil War, was riding his horse near his cabin in West Virginia—passing through dense wooded areas blackened by fire—when he stumbled upon a “luxuriant growth of fungi, so inviting in color, cleanliness and flesh that it occurred to me they ought to be eaten.” He wrote, “Filling my saddle pockets I took them home, cooked a mess, ate it, and, in spite of the prophecy of a frightened family, did not die.”

That edible epiphany in the Appalachian wilderness initially supplanted an unvaried fare of potatoes and bacon, and it soon became an all-absorbing quest: McIlvaine would taste every mushroom he found. By 1900, he had tasted at least 600 species and established himself as an eager experimenter. (By comparison, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Annual Report of 1885 recommended 12 edible species.) In a letter to New York mycologist Charles Peck, McIlvaine wrote, “I take no man’s word for the qualities of a toadstool. I go for it myself.”

In 1900, McIlvaine published a richly illustrated, 700-page tome, One Thousand American Fungi: Toadstools, Mushrooms, Fungi: How to Select and Cook the Edible: How to Distinguish and Avoid the Poisonous. “It ought to be in the hands of all who collect fungi for the table,” one naturalist said. McIlvaine offers 15 pages of recipes for cooking, frying, baking, boiling, stewing, creaming and fermenting mushrooms, including advice from Emma P. Ewing (early celebrity chef and narrative-cookbook author). He exhibits a remarkable ability to stomach mushrooms considered poisonous (he’s sometimes known as “Old Iron Guts”), but what’s remarkable is that his extensive, idiosyncratic commentary mentions not only the natural morphological variations, but also the range of culinary possibilities.

Consider the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus): “The camel is gratefully called the ship of the desert; the oyster mushroom is the shellfish of the forest. When the tender parts are dipped in egg, rolled in bread crumbs, and fried as an oyster they are not excelled by any vegetable and are worth of place in the daintiest menu.”

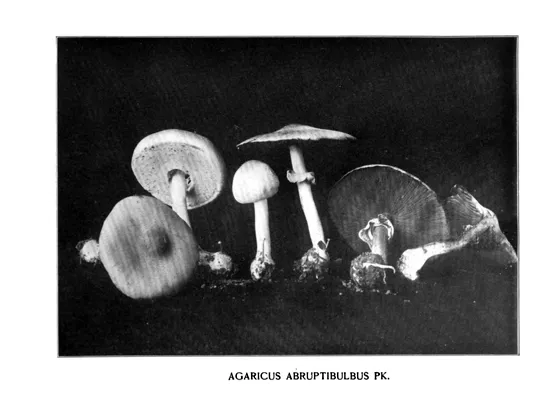

Or the woodland agaricus (Agaricus silvicola): “It has a strong spicy mushroom odor and taste, and makes a high-flavored dish. It is delicious with meats. It is the very best mushroom for catsup. Mixed with Russulae and Lacterii or other species lacking in mushroom flavor, it enriches the entire dish.”

Or the vomiting Russella (R. emitica): “Most are sweet and nutty to the taste; some are as hot as the fiercest cayenne, but this they lose upon cooking… Their caps make the most palatable dishes when stewed, baked, roasted or escalloped.”

Or even the parasitic jelly fungus (Tremella mycetophila): “Cooked it is glutinous, tender—like calf’s head. Rather tasteless.”

Outside the ranks of today’s amateur mycologists (the North American Mycological Association’s journal is called McIlvainea), the man who explored the furthest frontiers of American mycophagy is little known. There is no authoritative biography, no major conservation organization named for him. In fact, as David W. Rose writes, McIlvaine endures “through—rather than in spite of—his brilliant eccentricity.” McIlvaine maintained a private home for the insane; he was partial to whiskey and sexual dalliance (eventually leading to his expulsion from Chautauqua); his busiest years were marred by a “housequake” of a divorce, including allegations that his wife poisoned him (truly curious for a man who ate mushrooms now considered poison). He died of arteriosclerosis in 1909, at age 68 or 69.

John Cage, composer and devoted mushroom eater, wrote, “Charles McIlvaine was able to eat almost anything, providing it was a fungus. People say he had an iron stomach. We take his remarks about edibility with some skepticism, but his spirit spurs us on.” (Also curious to note: Something Else Press reprinted McIlvaine alongside Cage, Marshall McLuhan, Bern Porter, Merce Cunningham, and Gertrude Stein.)

McIlvaine’s book endures as an attractive guide to anyone with the faintest interest in fungi, less as a primer for collecting or for lining your cellar with horse dung and more as a reminder to amateurs: in order to eat these species, you must know them well. His spirit inspires us to head out far beyond the supermarket’s insipid white button mushrooms, to where the wild things grow, for a taste of something that might make Old Iron Guts proud without our joining him in the grave.