Charlotte Cushman Broke Barriers on Her Way to Becoming the A-List Actress of the 1800s

In the role of a lifetime, the queer performer was one of the first practitioners of ‘method’ acting

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/06/b306d7fe-c22e-4278-9ac3-21fda3292e7c/charlotte-cushman.jpg)

“Stella!” cries Marlon Brando, his contorted face and bared chest an eloquent advertisement for thwarted love. We typically associate “method” acting with mid-20th-century names like Brando and Lee Strasberg or, if we are theater nerds, with Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre. But the seeds of this transformative approach to theatre, where actors draw on personal experience to evoke more realistic performances, were sown much earlier, in the 19th-century of writer Walt Whitman.

In the 1840s, before he became a renowned poet, Whitman was a theatre aficionado and wrote about New York plays and actors in his columns for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. One evening he saw a new production of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist at the prestigious Park Theatre in downtown Manhattan and was amazed by a young actress named Charlotte Cushman who was cast in the role of the prostitute, Nancy. Cushman’s performance was “the most intense acting ever felt on the Park boards” Whitman wrote, and no one who saw her could help but marvel at “the towering grandeur of her genius.”

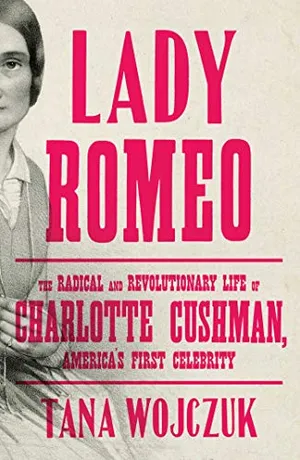

Lady Romeo: The Radical and Revolutionary Life of Charlotte Cushman, America's First Celebrity

This illuminating and enthralling biography of 19th-century queer actress Charlotte Cushman portrays her radical lifestyle that riveted New York City and made headlines across America.

Cushman would later become one of the most famous people in the world, and America’s first bonafide celebrity. But when Whitman first saw her, she was an up-and-coming performer; the role of Nancy was meant to be a fatal blow to her career. Cushman was a queer, masculine-looking actress with tremendous stage presence. She had angered at least one New York critic by beating out his girlfriend for roles, and her managers at the Park disliked her, despite her talent. By the terms of her contract, Cushman had to take any role her managers gave her, but she was furious when she read in the newspaper that they’d cast her as a prostitute. Nancy was not the plum role then that it is today, and actresses were already thought of as little better than prostitutes by the moralizing public. Newspaperman Horace Greeley’s Tribune often railed against the moral dangers of the theatre, which did allow prostitutes to service customers in the infamous “third tier.”

Cushman came up with a plan, and without telling anyone she ventured into New York’s infamous Five Points neighborhood where most of the city’s prostitutes actually lived. Similar in size and squalor to the slums Dickens evoked in Oliver Twist, Five Points housed the city’s immigrant poor, and it was where most young single women arrived and later died as women of ill repute. With very few jobs available to women, most who had no independent means or family to return to were forced into the sex trade. They were reviled by New York’s politicos but visited by many of the same men who decried them in the newspapers and pulpits.

Five Points was also home to the infamous “gangs of new york,” loose associations of boys and young men with names like “the dead rabbits.” A woman would rarely go there unless she was a dedicated social reformer, and she would definitely not go there alone without telling anyone where she was. Charles Dickens called the residents of five points to “animals.” Walt Whitman, on the other hand, saw the neighborhood as nurturing “the Republic’s most needed asset, the wealth of stout poor men who will work.” Walking alone along the same streets Whitman frequented, among the smell of roasted corn and the cries of the “hot corn girls,” Cushman would have heard music spilling out onto the street from nearly every bar and public house, and a new kind of percussive dancing born in Five Points called “tap.” When she got thirsty, she could buy a lemonade or shandy from a German street vendor or eat cheap oysters shucked in front of her eyes.

Cushman stayed in Five Points for several days, and when she emerged she had traded her clothes with a dying prostitute. These rags became her costume for Nancy. On the night of her first performance, she hid in her dressing room and emerged fully transformed. But it was what she did next that amazed everyone.

Nancy’s death scene was usually played offstage. Bill Sikes would pull her offstage and the audience would hear only the simulated sound of a gunshot. But Cushman’s Nancy wasn’t going out like that. She had planned with her co-star to perform Nancy’s death onstage. Sykes dragged her around by her hair, the audience screaming at him to let her go. He beat and abused her, but Cushman, bloodied, fought back. With her powerful physique it would have seemed possible that she might overcome her attacker, and Dickens’ story was only a few years old, so many in the audience would not yet know her fate. When Sikes finally killed Nancy on stage, in full view of the audience, the sound was “like a Handel festival chorus,” wrote the journalist John Hollingshead in his memoirs, deafening and rising as one to curse Sikes and wail for poor Nancy.

Cushman had done the impossible. By studying the prostitutes of Five Points she had seen them as real, pitiable women, and now she got the audience to see them that way as well. She transformed Nancy from a slattern into a martyr.

Method acting is experiential. To do it well, actors need to construct an often fragile bridge between their own emotions and their character’s. Actors who excel at method acting tend to seek out difficult experiences and “the method” as it is also known, now has the bad reputation of licensing some actors’ substance abuse and even violence. Journalist and stage director Isaac Butler, author of a forthcoming book on the topic, points out that defining the method is tricky business. “There's no consensus definition of the method,” he told me in an interview,, “it shifts over time pretty radically.”

We usually think of the Method, Butler notes, as an Americanized version of the techniques of Russian actor/director and artist Konstantin Stanislavsky at the Moscow Art Theatre in the late 19th and early 20th century. But “our definition of it is always shifting and how we define it today is not how Stanislavski would have defined it...Today we think of the Method as a practice of deep research in which you live the life of the character.”

Cushman’s approach to acting is one of the very earliest examples we have of the Method in America, the most comprehensive and true to what later became known as “Stanislavskian” naturalism. Edwin Forrest, the bombastic 19th century actor whose sexy legs were compared by contemporary critics to Hercules, boasted that he took inspiration from a near-death experience when he fell overboard on a boat. He claimed he was almost eaten by sharks.

Cushman on the other hand, began studying and mimicking people. As a child, she got in trouble for copying the mannerisms of her pastor while he was over at her house having tea. As an adult she drew all kinds of people to her from bureaucrats to Bowery b'hoys. Her first time playing Nancy was the first time we see her consciously risking her safety to study for a role.

Stanislavski believed, says Butler, that actors "play a human being, not a character type...you're not playing the romantic tragic hero, you're playing Juliet as a real person." By the time Cushman came on the scene, audiences were sick of seeing these types replicated again and again. She gave them something entirely new.

Cushman went on to play mostly male roles, like Hamlet and Macbeth, and these are what made her famous. Women had played men onstage before, but Cushman was totally believable, a “better man than most men” as one critic put it.

This was more than just a testament to her acting. Offstage also Cushman “played Romeo” to the many women she fell in and out of love with. She was criticized for looking “ugly” and manly, and her co-stars sometimes complained that her physical power made them appear weak. But to audiences, she embodied what they felt a man should be—passionate, sensitive, courageous and truth-telling. And these were characteristics she tried to embody offstage as well. She often dressed as a man offstage, though not for public appearances, and she lived openly with female partners although the 19th century press insisted on calling them her “friends.”

Ultimately, Cushman’s ability to make her characters real and immediate made audiences fall in love with her. By the time she died, she was one of the most famous people in the world. Tens of thousands of people held a candlelight vigil on the streets of New York (as many as mourned Charles Dickens), and in Boston, thousands more crowded outside the church where tickets for the funeral had long ago sold out.

They weren’t just saying goodbye to a celebrity, though, they were celebrating the woman who helped define American culture as something rich, complex and fluid. These trends would reverse themselves with the Victorians, but Cushman’s legacy continued in the artists and activists she inspired.

Tana Wojczuk is the author of the forthcoming biography Lady Romeo: The Radical, Revolutionary Life of Charlotte Cushman, America’s First Celebrity (Avid Reader Press and Simon & Schuster).

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.