Cheeky Charmer

For half a century, photographer Harry Benson has been talking his way to the top of his game

If you look closely at the newsreels showing the Beatles’ 1964 arrival at New York’s JFK airport, a "fifth Beatle" follows the Fab Four out of the airplane. He is distinguished not by the mop top of his colleagues but by a ’50s teddy boy haircut and a camera around his neck. Photographer Harry Benson pauses at the top of the stairs surveying the scene. Every time I see this clip I imagine he’s looking for the Time & Life Building.

Life magazine had been in Harry Benson’s sights for all the years he fought his way to the front of London’s Fleet Street rat pack. For that Beatles tour, he was on assignment for the London Daily Express, but when the rock group returned to England, he stayed in the United States.

It took another four years before he got his first Life assignment: a story about mothers in a small Nebraska town protesting the sexual content of movies. Persistence, enthusiasm and a willingness to take anything thrown his way led to more work from the magazine. His beguiling charm—effective not just on assignment editors but on his subjects as well—proved invaluable with people like the notoriously aloof Johnny Carson. By the end of 1971, Life’s editors were astonished to realize that Benson—a freelancer—had published more pages than many of the magazine’s high-profile staff photographers.

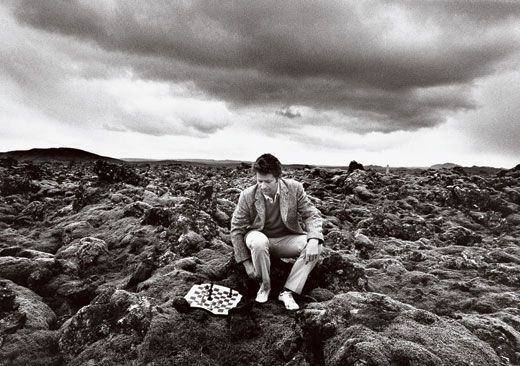

The next year (the weekly Life’s last) they sent him to Iceland to shoot the World Chess Championships. Enfant terrible Bobby Fischer, who was even then behaving erratically, was challenging Soviet Boris Spassky in what was one of those occasional symbolic East versus West showdowns of the Cold War. Benson got to spend the summer in Reykjavik with Fischer. And a large contingent of the world press.

Photographing an international chess match is about as visual as a U.N. treaty debate. All aspects of the venue down to the chairs and lighting are the result of laborious negotiations. The participants—brooding eccentrics, both—were held in isolation by their handlers. And photographers were confined to a gallery where they were presented with the same dreary picture of two men staring at a game board for hours on end.

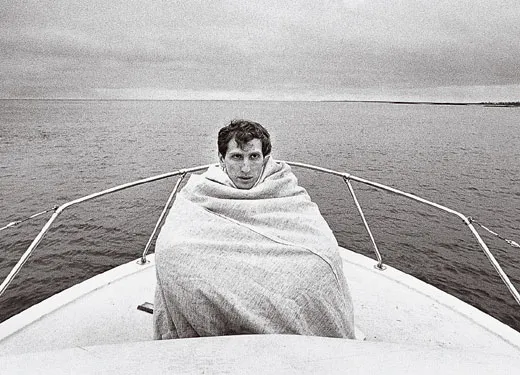

Within these stultifying confines, Benson’s genius blossomed. His contact sheets showed Fischer in his private quarters. Fischer getting fitted for a new suit. Fischer brooding on the deck of a private cruiser. Fischer in a pasture being nuzzled by ponies! And then, in came the rolls of Spassky, including one improbable picture of him working out moves on a foldup chess set on top of a rock in the middle of a field of moss-covered lava boulders.

In an event that was a nonevent photographically, Benson had not only gotten behind the scenes but had successfully invaded both warring camps to produce lively, telling and exclusive pictures. The depth of his involvement became clear when, after visiting with Spassky, Benson was the one to tell Fischer that Spassky would concede the tournament the next day. "In situations like this, there’s usually one friend in the enemy camp," Benson recalled years later. "I thought, it might as well be me."

Some other photographers may have the same or better command of their equipment, quick reflexes and an eye for composition. What sets Benson apart is his uncanny ability to quickly size up his subjects and then use his wits to get them into a situation where they reveal themselves in a storytelling photograph.

Until the emergence of Harry Benson’s pictures in American magazines (first at Life and then at People, New York and Vanity Fair, among others), this style of imagery had been largely absent from mainstream photojournalism in the United States. What had pervaded Life and other "serious" picture magazines since the 1950s was a kind of reverential approach to a subject, typified by the work of W. Eugene Smith; the story was told in a series of dramatic images artfully arranged over several pages with text blocks and captions in what was known as the picture essay. Many of its practitioners thought this "concerned photography" could change the world.

By comparison, Benson’s photographs were irreverent, gritty, casual and stagy—sometimes outrageously so. They told the story in a single image usually played large, dictating the headline and bending the writer’s narrative around it. As Benson’s success grew, other photographers, who had first disdained his approach, began to adopt it. People magazine, which was launched in 1974, became his showcase (he shot its third cover) for a kind of quick-hit, cheeky, illustrative photojournalism.

During his formative years on Fleet Street in postwar Britain, there were ten or more daily papers racing to cover the same story. Because of an efficient rail system, many of the London papers were national newspapers as well, so their readership exceeded that of all but the largest American dailies.

In this cauldron of competition a photographer needed agility, persistence and a badgerlike cunning to survive. There was no place for artifice; no time for permissions (better to beg forgiveness later, after the paper had gone to press). With a pack chasing every story, the successful photographer was the one who got there first, and when that was not possible, the one who managed to get something different. And if that meant convincing an apprehensive World Chess Champion to sit in a field of lava boulders on a rainy day outside of Reykjavik, that’s what you did.