Christo’s California Dreamin’

In 1972, artists Christo Jeanne-Claude envisioned building a fence, but it would take a village to make their Running Fence happen

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Christo-Running-Fence-631.jpg)

Lester Bruhn never claimed to have an eye for art. So the California rancher wasn’t sure what to do one afternoon in 1973, when a couple knocked at his door and introduced themselves as Christo and Jeanne-Claude. The strangers asked, in accented English, if Bruhn would consider leasing them land to erect a temporary art project: a large fabric fence that would stretch across ranches and highways before dipping into the ocean.

Bruhn may have been a bit apprehensive as he sized up the two artists. But unlike the handful of ranchers who had turned the couple away, he invited them in for coffee.

“I guess he saw something nobody else saw,” says Bruhn’s daughter, Mary Ann. “My father was just totally entranced.” Lester Bruhn died in 1991 at age 82.

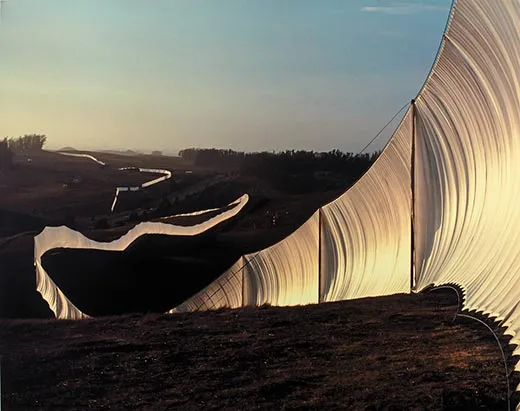

More than 35 years after that first meeting, thousands of people are still entranced by The Running Fence—an 18-foot-high stretch of white, billowing nylon curtains that extended 24.5 miles along the hills of Sonoma and Marin counties for two weeks in September 1976. It took three and a half years to prepare.

Now, for the first time, the documentation of the entire project—from Christo’s initial sketches to pieces of the fence itself—is on display, through September 26 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in an exhibition called “Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Remembering The Running Fence.”

The effect of the artwork, Christo recalled at the exhibition première on March 30, is the real story: how the vast fence, rather than separating people, embodied “togetherness.”

Inspired by a snow fence they saw while driving along the Continental Divide in 1972, Christo and Jeanne-Claude envisioned a large installation that would enhance the topography of the land. The actual fence crossed 14 major roads and went through only one town: Valley Ford. Art wasn’t something the “old-timers” there had much experience with, recalls Mary Ann. But her father saw it as an opportunity. The project could help the economy, he insisted, creating jobs and boosting tourism.

The artists and the Californian rancher reached out to Bruhn’s neighbors with a proposal: the artists would pay the ranchers for the use of their land, and after the fence came down, all the building materials would belong to the ranchers.

Ultimately the ranchers decided it was a good deal. Some artists and urbanites, however, were not as enthusiastic. They formed a group called the Committee to Stop the Running Fence, dragging out permit hearings with claims that the fence would wreak havoc on the land. More than one artist said the project wasn’t art.

Finally, after 18 public hearings and three sessions in the superior courts of California that stretched out over two years, the project was approved. Beginning in April 1976, roughly 400 paid workers rose before dawn every day to stretch 240,000 square yards of heavy, woven fabric across the landscape using 2,050 steel poles.

Members of Hell’s Angels motorcycle clubs worked alongside art students. And when the fabric fence was finished, visitors from across the country flocked to see the curtains illuminated by the bright California sun, catching the wind like vast sails. “It went on and on and on, twisting and turning over those hills,” Mary Ann says. “It was magnificent.”

Today, in the center of Valley Ford, an American flag hangs on one of the fence’s steel poles, and beneath it Christo’s duct-taped work boots—worn down from walking the length of the fence countless times—are sealed in a metal time capsule. There was even a reunion picnic held in September 2009, which Christo attended with Jeanne-Claude, who died two months later, at age 74.

At the exhibit’s opening, Mary Ann, now 71, wore a shimmering white blazer—made from fence fabric that once graced her father’s land.

“To talk about the fence is one thing; to see it was another,” she says. “It got to you.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)