Clan-Do Spirit

A genealogical surprise led the author to ask: What does it take to be one of the family?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/reunion_sept08_631.jpg)

When I was 20 years old, I crammed my most valued possessions into a big purple backpack and moved to Prague. This was in the mid-1990s, when the city was buzzing with American expats—writers, artists, musicians, bohemians—searching for the modern-day equivalent of Hemingway's Paris. The city's gothic, winding, Escher-like streets were bustling with energy, but when it came to Jewish life, the city was a ghost town. Late at night I would walk through the vacant Jewish quarter, with its many moss-covered tombstones shrouded in fog, and I would feel like the last Jew alive.

One evening, I wandered into a dimly lit antiques shop behind Prague Castle and found a tray stacked with gold and silver rings bearing family crests. "What are these?" I asked the storekeeper.

"They are old family rings," she told me.

"Where did they come from?" I asked.

"From Jewish families," she answered curtly.

Eventually, as my loneliness and alienation mounted, I called my great-uncle back in the States and asked if we had any relatives left in Eastern Europe. "No," he said. "They all perished at the hands of the Nazis."

At that moment, and for a number of years afterward, I hated all things German. And so it came as quite a shock when I discovered, several months ago, that I might have relatives in the Old World—blond-haired, blue-eyed, gentile relatives in Germany.

This information came from my mother's cousin, a devoted genealogist, who had learned about a large clan in Germany named Plitt. This was news to me, even though my mother's maiden name is Plitt, and my full name is Jacob Plitt Halpern. Apparently, this clan even had its own Web site, which traced the family's roots back to one Jacob Plitt, who was recorded in 1560 as paying taxes in the mountain town of Biedenkopf in the state of Hesse.

As last names go, Plitt is pretty unusual: according to the U.S. census, it ranks 28,422th in this country—well behind Jagodzinski, Przybylski, Berkebile and Heatwole. I had never known a Plitt outside my immediate family, but on the German Plitts' Web site I discovered that they held a family reunion every couple of years. Typically these gatherings are held in Germany, but the next one, I saw, was to be held in Rockville, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C. A posting on the Web site noted that there would be special events featuring the Jewish side of the Plitt family.

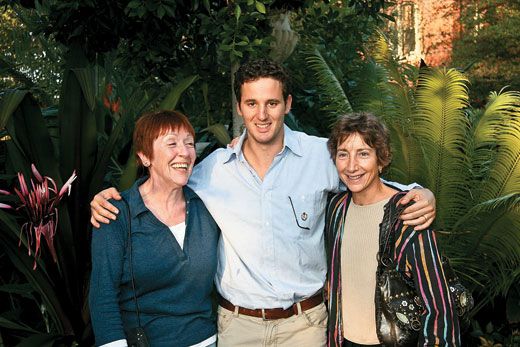

In the coming weeks, I passed this information along to the other Plitts in my family. They took it tepidly. No one seemed excited by the prospect that our family tree might include a few gray-haired former Nazis who had been "rehabilitated" into Mercedes assembly-line managers. Yet, as much as I bristled at the thought of being related to this tribe of Germans, the thought of not attending seemed neurotic and provincial. Ultimately, I shamed myself into going. I even browbeat my mother and younger brother into going with me.

So one morning not long ago, I found myself in a conference room at the Rockville Hilton with two dozen putative relatives, listening to a woman named Irmgard Schwarz talk about the estimable history of the Plitts. Irmgard, one of a half-dozen German Plitts who had traveled to Maryland for the reunion, is the keeper of a massive tome that traces the family's lineage in meticulous detail back to the early days of the Renaissance. That rich a genealogy is highly unusual in Germany, where a number of armed conflicts, such as the Thirty Years' War (1618-48), destroyed many tax records and church archives.

Throughout the morning, Irmgard helped a number of American Plitts figure out how they were related, but there were a handful of attendees who had found no connection to the original Biedenkopf clan. Some of them were Jews who traced their origins to Bessarabia, or modern-day Moldova. Their ranks included an architect named Joel Plitt, an author named Jane Plitt and my mother, brother and me. We jokingly called ourselves the Lost Tribe of Plitt, and as the four-day gathering progressed, the mystery surrounding us seemed only to grow. "I hold on to the belief that there is a connection between the families," one of the gentile Plitts told me over lunch. "But it's just a feeling."

Until recently, the German Plitts had had no idea any Jews shared their last name. In 2002, at the previous international Plitt reunion in Maryland, Jane Plitt became the first Jew to attend—only she didn't tell anyone that she was Jewish. "I was totally intimidated," Jane told me at the Rockville Hilton. One Plitt, she said, "asked me five times what church I attended. I never told him. I was very adept at changing the conversation." But Jane also befriended Irmgard at the 2002 reunion and, weeks later, broke the news to Irmgard in an e-mail.

Jane couldn't have picked a better confidante. "When I was 14 or 15 I began reading all of these books about Jews, and I built up a small library on Judaism," Irmgard later told me. "Very often, during this time I thought, I would like to be Jewish! Which is silly, because if I were Jewish, my family wouldn't have survived the war."

According to Irmgard, who was born in 1947, Germans still weren't talking much about the Holocaust when she came of age in the early 1960s. Her interest in this dark chapter of history was unusual, and she says that it became an "obsession." Many times, she said, she questioned her own parents about how they had spent those years, and she never accepted their claims that they had been powerless to challenge the edicts of the state. As an adult, she made five trips to Israel, and she entertained the fantasy that her son would marry a Jewish woman and provide her with Jewish grandchildren.

At the 2003 Plitt reunion, which was held at an ancient German monastery in Eltville, Irmgard stood up and announced, matter-of-factly, that there were Jews in the family. She even suggested that the entire family might originally have been Jewish. She left unmentioned the possibility that the Jewish and gentile Plitts were unrelated. On some level, Irmgard says, her intent was to rattle some of the older and more conservative family members. This she did.

"People were shocked," recalls Brian Plitt, a gentile Plitt from Washington, D.C. "You could see it on their faces—they were like, Holy Moly! There were some older people there who were in their 80s, and you could just see them shaking their heads: no, no, no."

In 2005, Jane Plitt went to Germany for that year's reunion. At the banquet that marked the high point of the gathering, the German Plitts chanted the Hebrew song "Hevenu Shalom Aleichem," whose ancient lyrics go: "We bring peace, peace, peace upon you." Jane was both surprised and moved. "I guess they had time for the idea to sink in," she told me.

By the time we Plitts had gathered in Rockville, any communal shock seemed to have subsided and been replaced by a pressing curiosity: Were we really related? And if so, how?

During a seminar devoted to those questions, Jane and Irmgard offered two possibilities. The first, dubbed the "romantic theory," proposed that a young gentile Plitt had departed Biedenkopf, married a Jewish woman in Bessarabia and converted to her faith. The second, the "practical theory," held that the family's patriarch, Jacob Plitt, had converted from Judaism to Christianity or descended from someone who had.

According to Elisheva Carlebach, author of Divided Souls: Converts From Judaism in Germany, 1500-1750, neither theory is likely. The romantic theory is especially suspect, Carlebach later told me, because conversion to Judaism was considered heresy by the Church. The practical theory is also problematic. Jews who converted to Christianity almost always adopted a new last name, such as Friedenheim (meaning "freedom") or Selig (meaning "blessed"), to reflect their new identity.

I found Carlebach's skepticism bracing, and yet, to my surprise, some deeply sentimental part of me yearned for one of the two theories to be true. I suppose I hoped that the blood relationship itself would serve as proof that the ethnic and religious distinctions that we make among ourselves are ultimately arbitrary. And I was not the only one who felt this way.

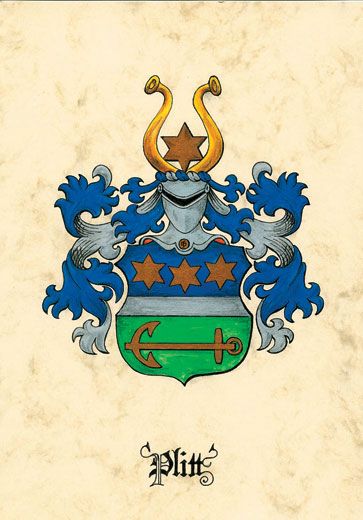

In fact, I found no one at the reunion who acknowledged the possibility that our shared last name was simply a coincidence. We seized upon any and all commonalities—thyroid conditions, almond-shaped eyes, stubbornness, even entrepreneurial success—as signs of our shared heritage. The most exciting and mysterious "evidence" involved the Plitt coat of arms. At first glance, its iconography seemed straightforward: a shield, an anchor, a knight's helmet, several stars and two elephant trunks. Upon closer examination, however, I noticed that the stars are six-pointed, like the Star of David, and that the elephant trunks resemble shofars, the ritual horns of Israel. For a moment, I felt like Professor Robert Langdon in The Da Vinci Code. Only slowly did I realize how desperate I had become to find a connection to my fellow Plitts.

On the final day of the reunion, almost everyone made a field trip to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. I walked through the exhibits with Irmgard at my side, and we shared a prolonged and awkward silence. At one point, as we watched a short video about the Nazi Party, she told me that her father had been a member of the Sturmabteilung, or SA, a gang of thugs also known as the brownshirts or storm troopers, who were instrumental in Adolf Hitler's rise to power. "He joined early, in 1928, when he was just 20 years old," she said. "He never talked about it. In fact, I only discovered this through my sister, many decades later."

That night, as we gathered for one final dinner in the Hilton ballroom, Irmgard stood up and led us in a round of Hebrew songs. She sang quite well, and her Hebrew was so good that she corrected my pronunciation of the final verse of "Shalom Chaverim."

"How do you know these songs so well?" I asked her.

"It's in the genes!" someone yelled out.

As it turns out, that's not likely. Shortly after our Rockville reunion, half a dozen Plitts, both Jewish and gentile, underwent DNA testing. (I did not participate because the test they used examines the Y chromosome and was therefore restricted to male Plitts. I am, of course, a Halpern.) According to Bennett Greenspan, the founder of Family Tree DNA, the testing service that we used, there is a 100 percent certainty that the Jews and gentiles who were tested have no common ancestor within the past 15,000 to 30,000 years.

I was disappointed, of course. But that feeling soon gave way to a vague sense of hope. After all, why should it take a bond of blood for human beings to regard one another as kin? Isn't it a greater feat to set aside old prejudices in the name of humanity? If our connection to one another were founded on choice rather than obligation, wouldn't it be a more meaningful bond?

We'll find out, we Plitts. The next gathering in the United States is scheduled for 2010. Irmgard has already told me she'll be there, and I know I will, too. My mother, who had her misgivings before her first Plitt family reunion, has volunteered her house in the Berkshires for this one.

Meanwhile, as word of the DNA results spread, Jane Plitt sent out an e-mail saying, "The Plitt branches are ancestrally distinct, but the choice to embrace each other as family, regardless of religion or DNA data, remains very real." I find it reassuring, if odd, that even news of ancestrally distinct DNA hasn't ruptured the "family."

Jake Halpern is the author of Fame Junkies: The Hidden Truths Behind America's Favorite Addiction. He lives in Connecticut.