The French art critic Louis Vauxcelles described a day trip to Giverny in summer 1905, to visit the home of artist Claude Monet. The painter wore “a suit made of some tweedy material in a beige check, a blue pleated silk shirt, a hat of tawny suede, and high-cut shoes of reddish leather.” After lunch, the genial fop hastened his guest to the pond because “the water lilies close before five.” Vauxcelles was drowsy with delight.

“The leaves lie flat upon the surface of the water, and from among them blossom the yellow, blue, violet and pink corollas of that lovely water flower. … Weeping willows and poplars abound, and on the banks of the stream he has planted hundreds of flowers—gladioluses, irises, rhododendrons and some rare species of lily. … It all comes together to create a setting that is more pretty than grandiose, an exceedingly Oriental dream.”

The effect was repeated in the studio, housing depictions of water lilies “at all hours of day: the pale lilac of early morning, the powdery bronze glow of midday, the violet shadows of twilight.” The artist ended the day by giving instructions to his gardener, out on the pond, “in a barge removing the dead vegetation from among the water lilies.”

The precious flowers, drifting, their movement almost imperceptible, over the liquid blue-green surfaces of the artist’s Water Lilies paintings, evoke a dreamy contentment, as if the world is in slow motion, or time is stilled altogether. Monet himself drew analogies with poetry and music, mentioning Mallarmé and Debussy, who composed his “Reflets dans l’eau” (“Reflections in the Water”) in 1905.

The school of art known as Impressionism had been flourishing since April 1874, when Monet and several of his contemporaries—Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Alfred Sisley and Paul Cézanne—held a group show in Paris. The artists knew each other from painting classes, or from frequenting the same café, but they didn’t consider themselves part of any unified school. For the show, they called themselves “The Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, etc.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d6/74/d674fa51-ac8e-47fb-a599-47b7ca6c8c01/sepoct2024_f11_monet.jpg)

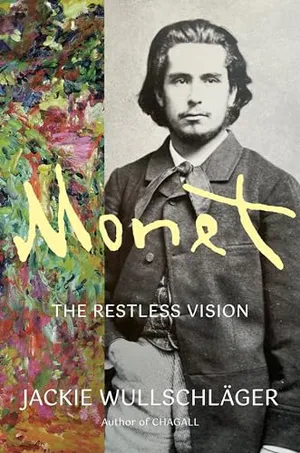

Monet: The Restless Vision

Drawing on thousands of never-before-translated letters and unpublished sources, this biography reveals dramatic new information about the life and work of one of the late 19th century’s most important painters.

It was a painting by Monet, called Impression, Sunrise, that gave the up-and-coming artists their public identity. Jules-Antoine Castagnary, a writer for the newspaper Le Siècle, put it this way: “If we must characterize them with one word, we would have to coin a new term: impressionists. They are impressionists in that they render not the landscape but the sensation evoked by the landscape. The very word has entered their language—not ‘landscape’ but ‘impression’—in the catalogue title for M. Monet’s Sunrise.”

Monet himself would later describe his method to a young painter: “When you go out to paint, try to forget what object you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever, merely think, there is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives your own naive impression of the scene before you.”

By his late 20s, Monet had brought to an apogee that approach of fragmenting brushstrokes and interplaying, and dazzling vibrations. Adopting yet smaller, comma-like brushstrokes, he moved further from defining forms in favor of lively marks, dots, bursts of color, which give an overall impression of the sensation and atmosphere of a scene. To traditional eyes, the effect looked ungainly—“a debauch of impasto … the most disheveled and the most disorderly type of painting that one can imagine,” said the artist Frédéric Chevalier. But a paradigm had shifted, and Monet became a magnet for his forward-looking contemporaries.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0f/2a/0f2ac22f-6369-4f8c-b97e-e69d116b684c/sepoct2024_f09_monet.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ab/d8/abd80922-72ac-41f0-b53b-f1d79d79965a/sepoct2024_f16_monet.jpg)

Now, in his garden at Giverny in 1905, the artist was 64, and his Water Lilies were like nothing that had existed in painting before: nature rendered in the cropped, smallest fragment of a landscape, so that the lilies appeared “to be floating in the moist air, fading away and promoting the play of imagination,” wrote Roger Marx, the most perceptive contemporary witness, who interviewed Monet about the work. He thought Monet had now “severed his last ties” with descriptive painting. The paintings were in this sense paradoxical: They pushed Impressionism toward abstraction, but as representations they made a particular place, the Giverny pond, iconic.

At the time, it was an extreme move to withdraw to sit beneath a big white parasol to depict, with no certainty of the outcome, a slice of water as a self-contained contemplative space. “The basic element of the motif is the mirror of water, whose appearance changes at every instant because of the way bits of the sky are reflected in it, giving it life and movement,” Monet explained to the journalist François Thiébault-Sisson. “The passing cloud, the fresh breeze … a rainstorm, the sudden fierce gust of wind, the fading or suddenly refulgent light … create changes in color and alter the surface of the water. It can be smooth, unruffled, and then, suddenly, there will be a ripple, a movement that breaks up into almost imperceptible wavelets or seems to crease the surface slowly, making it look like a wide piece of watered silk.”

It was, he added, “exceedingly hard work, and yet how seductive it is! To catch the fleeting minute, or at least its feeling, is difficult enough when the play of light and color is concentrated on a fixed point, a cityscape, a motionless landscape. With water, however, which is such a mobile, constantly changing subject, there is … a problem that is extremely appealing, one that each passing moment makes into something new and unexpected. A man could devote his entire life to such work.” For nearly a quarter of a century, Monet did.

A push-pull between control and freedom, of brushstrokes, of the lilies, floating, opening and closing as they liked, characterizes the series, and the garden itself. Sky and earth mostly disappear, the banks and edges are eliminated, no single point fixes the eye in these decentralized, water-flooded compositions. Monet played on tensions between the expansive surface, the watery depths and its interpenetrating flowers and tangled foliage, which by turns absorb or reflect light.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bc/0b/bc0bc9ab-d51e-4e8c-bbd2-081f646a9595/sepoct2024_f06_monet.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/37/06/3706566a-eaba-4dcd-aabe-c9050e14a812/sepoct2024_f01_monet.jpg)

Year by year, Monet wrought variations in tone and color and experimented with different formats, including his only paintings in circular tondo form. In three square canvases in 1905, he expands the view out to the Japanese bridge, and clusters of lilies with their flat spreading pads seem to roam freely. In 1906 a hazy quality intensifies, like a mirage.

The innovation in 1907 was vertical canvases, unusual for landscape pictures. A burst of dazzling light streams down from the top, twists through foliage and spills into a broad eddying pool. The effect is bleached out, disorienting, as the aggressive spurt energizes the passive motif.

Monet’s private letters—most of which have never, until now, been translated into English—show clearly how radical these pictures were for their time. His art dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, had to admit he did not like them or think he could sell them. It was the first time he balked at Monet’s work. Not that buyers were Monet’s immediate concern. Of the paintings in 1907, the artist informed Durand-Ruel, “I really have too few satisfactory ones to bother the public.”

To produce a coherent body of work from paintings of barely tangible fluctuations was a challenge that, over time, became exasperating. On some areas of the canvases, Monet thickly applied layer upon layer of paint, and a vast range of pigments, but “it’s still just sketching and research,” he wrote after four years. He became a prisoner of the streaming inwardness of the paintings, where water seems to flow into itself, as the mind circles.

He took a self-portrait photograph of his straw-hatted reflection as a silhouette in his pond—Narcissus staring at what he had created in order to double and recreate again. It is a beautiful, troubled image of an introspective Monet, enthralled but confronting himself, aging, and his art, as well as his familiar challenges, climate and light. The mythical Narcissus dies from frustration, as the Roman poet Ovid described: “The shadow that you see is the reflection of your image; / It is nothing in itself; it arrived with you and remains with you; / With you it will go away, if at least you are able to go away!” But Monet could not go away from the motif he had created. To stare at the pond was to stare at himself.

Over the decades, he had conquered seas and rivers, cathedrals and cities, “scenes complete in themselves,” as Roger Marx put it. Now he extended the omnipotence of his eye by creating his own world of nature. The water garden really was the outdoor studio he had always trumpeted. He dug the pond and altered its contours like a drawing; he diverted rivers, planted trees, sketched out curving paths, strewed lilies across the water like flecks of the brush and painted it all as a dissolving fragment. Marx thought that the paintings manifested “an authority and independence, an egocentric quality.” Observers were struck by the self-indulgence of the process. “He paints in spurts, working in fits and starts as the fancy takes him. When he feels in the mood to paint, no one is allowed to disturb him—friends, visitors, buyers—no one. And then he will let a week go by without touching his brushes,” Vauxcelles reported.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/86/8d8684a5-2c57-40d3-ba51-f67bdcfa7e64/sepoct2024_f17_monet.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/72/32/7232dfc8-e5c8-409b-a0bf-a75574b3d20f/sepoct2024_f10_monet.jpg)

His wife, Alice, fretted both when he did too much—“Monet works like one enraged and to excess, and I torture myself fearing exhaustion for him”—and when he faltered. Three years into the series, in 1906, his spirits were unpredictable. On a wet day, “Monet, furious, watches the pouring rain, which ruins everything. He is desolate, he takes it out on everything which surrounds him, which is really upsetting.” His victims tended to be younger men; perhaps they sparked resentment. Alice wrote that her son, Jean-Pierre Hoschedé, “was very badly received when he said that with our fine Panhard [an early French automobile] we should take to the road. It made him furious and he left the table.” She added, “How sad to be unable to be happy and to spoil the last days of one’s life like this.”

Few people could pull Monet from Giverny. An exception was Renoir. In autumn 1906, Monet spent some days in Paris to allow his friend to sketch his portrait, a pencil drawing of a warm-eyed, bushy-bearded, smiling Monet. Alice reported them “very happy to see one another.” Arthritic, incapacitated but working consistently, Renoir was held up as an example in Giverny: “When you see that condition, how unfair it seems of Monet with his good health to be in such a bad mood and not to do anything.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/40/2e/402e1150-54a1-4b43-a295-e9713a880ced/sepoct2024_f04_monet.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/71/55/71559c79-0334-4e9c-ac23-decba9aa5c40/sepoct2024_f03_monet.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9c/f0/9cf08ba1-782f-4176-8244-185d764e6c10/sepoct2024_f02_monet.jpg)

Renoir and Monet were together when news of Cézanne’s death, in Aix on October 22, 1906, reached Paris. The pair were the last surviving members of the original group and now experienced unexpected shifts in their relative reputations. Cézanne, born the year before Monet, had lived just long enough to see his reputation rise. In 1900, Pissarro had noted that Cézanne’s geometrical objects and planes were suddenly “very much in vogue, it is extraordinary.” In the next few years, Cézanne’s aim “to make of Impressionism something solid” resonated with the emerging, analytical generation who reacted against Impressionism, searching for structure and firmness, and concentrating on the figure.

Durand-Ruel refused to touch Cézanne, pronouncing him dull compared to Monet or Renoir. But in 1907, Cézanne’s posthumous retrospective at the Salon d’Automne was a sensation. When Monet’s work was going badly, Alice turned the Cézannes in his collection to the wall. “You have nothing to fear from the proximity of Cézanne,” Durand-Ruel’s son Joseph reassured Monet in 1908. It is the only known reference to Monet’s self-doubt vis-à-vis another artist.

The new battleground for artists was the figure, not landscape. For the first time in his career, Monet was aware that he was no longer central to the conversation. But he carried on, as Roger Marx put it, “pursuing the renewal of his art according to his own vision and his own means.”

Coming to the end of the second Water Lilies series, he already looked ahead to building on it toward something yet more abstract, imagining an immersive “grand decoration.” He revealed to Marx in 1909 the intention, not fulfilled for many years, “to use water lilies as a sole decorative theme in a room. Along the walls, enveloping them in the singleness of its motif, this theme was to have created the illusion of an endless whole, of water without horizon or shore. Here nerves taut from overwork could have relaxed, lulled by the restful sight of those still waters … a refuge for peaceful meditation.”

For all their differences, around the same time Henri Matisse expressed a similar ideal of an art of balance and serenity as soothing as a good armchair for a tired businessman. In both cases, what looked lucid and pleasurable, the equilibrium and rational delight of French painting made new for modern art, was complex and nerve-racking to create.

“I am very tough on myself,” Monet admitted in 1907. “I have just destroyed at least 30 [canvases], to my great satisfaction.” He worked so hard, and became so fraught with the difficulties of this series, that in 1908 he collapsed, soon after he had agreed to display the Water Lilies at Durand-Ruel’s, even though “from the moment that my new paintings didn’t gain your complete approval, it seemed to be difficult for you to do the exhibition.”

Monet suffered from vertigo and blurred vision, his signals of acute stress, and could neither complete nor judge the paintings. Was his reluctance to put new work before the public intensified by the posthumous blaze around Cézanne at the end of 1907? All spring, Monet was, he complained to Durand-Ruel, “not well, very tired, vertigo troubles me and I see less and less clearly. I see the moment when I will be forced to stop all work.”

Alice watched as he destroyed painting after painting. On April 15 she wrote, “Yesterday was bad for him, he destroyed three canvases and alas it’s often like this”; the next day, “He only blames himself, for his age, his powerlessness, he says.” On April 24: “I have spent terrible days watching his anxiety, his discouragement. I had all the trouble in the world to stop him writing to Durand that he’s giving up the exhibition.” On May 4: “What a Sunday. … Monet, already so badly disposed in the morning, refused to come to lunch and stayed shut up all day in spite of our entreaties. How sad it is when one has health, happiness, to make life a hell!” On May 5, Monet canceled the exhibition: He has “written to Durand that he has shut his door to the world.”

Monet’s exhibition had been so eagerly awaited that its cancellation was world news, suggesting the reach of his global fame—thanks to Durand-Ruel, who had been promoting his work in America since 1886. On May 16, 1908, the Washington Post reported that Monet had ruined $100,000 worth of pictures just before the exhibition, which “already had been advertised in the French papers. … With a knife and paint brush he destroyed them all.” The London Standard claimed superior knowledge, announcing, “M. Monet has not sold or delivered a picture since 1904” and the new ones were “‘overworked,’ that is, they showed too plainly how long they had stood on the easel. One of M. Monet’s friends even went so far as to say that there were four or five different pictures on each canvas.” Having cut a few to shreds, Monet, “extremely irritable and morose,” turned them to the wall and would “go away for change and rest.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/98/4d/984d98ec-4123-441a-b8b4-2a291f5517b0/sepoct2024_f07_monet.jpg)

Then on June 6, 1908, Alice’s 77-year-old brother-in-law Auguste Remy, a wealthy banker, was stabbed to death in his Paris home, by a conniving butler who had secured access to his wife’s money and jewelry boxes. This, too, made international news: American papers reveled in a tale of Parisian decadence exemplified by the “astounding state of affairs in the banker’s household.”

After Remy’s funeral in Paris, Alice reported, “My dear Monet has got back to work at last, which isn’t too soon.” Some 80 Water Lilies had survived the culls, and having their motif constantly before him, infinitely open to revision, was a blessing and a curse. Monet said in August that “these water landscapes have become an obsession. They’re beyond the strength of an old man, but I want to succeed in rendering what I feel. I’ve destroyed some, I’ve started again, and I hope that with so much effort, something will come of it.”

At the end of Monet’s life, he struggled with impending blindness. In January 1921 he gave an interview to Marcel Pays for Excelsior explaining that he saw “less and less,” and managed to work only as long as “my paint tubes and brushes aren’t mixed up. … I will paint almost blind, as Beethoven composed completely deaf.” He told the art critic Arsène Alexandre in May that he noticed his vision “diminish every day, almost every hour,” and the statesman Georges Clemenceau a year later that “my sight is going completely and if you knew what that meant for me”—yet “the wisteria has never been so lovely.”

His vision did not straightforwardly decline; there were better and worse phases. Eyedrops in 1922 allowed him for a time to “see as I haven’t for a long time. … I see everything in my garden. I rejoice in all the tones,” and he may have used these periods to make adjustments. That year, he finalized the donation of a Water Lilies series to the Musée de l’Orangerie, the art gallery in Paris next to the Place de la Concorde. He helped an architect create two special oval rooms, and he insisted on skylights for natural light.

After Monet’s death in December 1926, the agreed-upon Water Lilies panels went to the Orangerie. There they were ignored for two decades, hardly visited or mentioned, often covered up for other exhibitions to take place in the large space. The cause was the art historical moment. While Cubism extended its long reach across the first half of the 20th century, Cézanne’s authority reigned. In 1939, Lionello Venturi, editor of Cézanne’s first catalogue raisonné (catalogue of complete works), dismissed Monet as the “victim and gravedigger of Impressionism.” Few defenders who had known him well remained.

The actual, living water lilies on the pond fared well initially. They were cared for by Blanche Hoschéde Monet, the artist’s stepdaughter who also became his daughter-in-law after she married his eldest son, Jean. Blanche looked after the house and garden at Giverny, altered nothing, and began to paint it herself. After Blanche died in 1947, the garden was neglected. Several of Monet’s Water Lilies canvases that had never been displayed were stacked against crumbling walls in the studio. Birds flew in and out of broken windows, and the garden, too, became a wilderness.

Yet it was during this decline that, in 1949, the American abstract painter Barnett Newman told the director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York that he traced his own creative lineage to the painter of the Water Lilies: “Don’t tell me who my father is, my father is not Cézanne. … My father is the late Monet, and you don’t have one in the Museum of Modern Art collection.” Soon afterward, Monet was anointed precursor to American abstraction. His “influence is felt,” pronounced the art critic Clement Greenberg in 1957, “in some of the most advanced painting now being done in this country,” and the Water Lilies “belong more to our time, and its future, than do Cézanne’s own attempts at summing up statements.”

In effect, painting after the Second World War caught up with what Monet had been doing during the First World War, and curators and art historians started to catch up, too. In 1955, MoMA acquired its first large Water Lilies canvas. Through the 1950s, to fund his passion for safaris in Africa, the artist’s second son, Michel Monet, sold Water Lilies to other American museums, and there were exhibitions including them on both sides of the Atlantic.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/39/a5/39a53879-cac3-41de-9fc9-c462de83f114/sepoct2024_f08_monet.jpg)

In 1980, Robert Hughes’ book The Shock of the New connected the all-over skeins of paint on the Water Lilies canvases to the abstract paint splatters of Jackson Pollock’s groundbreaking Lavender Mist and cast Monet as a presiding spirit for the 20th century: “For the pond was as artificial as painting itself. It was flat, as a painting is … the pond was a slice of infinity. To seize the indefinite; to fix what is unstable; to give form and location to sights so evanescent and complex that they could hardly be named—these were the basic ambitions of modernism.” In 2016 the Royal Academy’s landmark exhibition “Painting the Modern Garden” showed how, from the 1860s to the 1920s, Monet wrought the most original effects from the motif of his enclosed “avant-garden.”

To create great art from that lightness of being and nonchalant amplitude was a far-reaching gesture. Monet painted the milieu he loved, making it at once thrillingly recognizable and compellingly disconcerting. His underlying values remain for many today: secular humanism, democratic leisure, pleasure, tolerance, truth to individual experience. For us, as for his first audiences, Monet’s painting offers respite from an increasingly technological, urbanized world.

From the book Monet: The Restless Vision by Jackie Wullschläger to be published by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Jackie Wullschläger.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x747:801x748)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/6a/c46a506d-32a7-44a6-9851-5f0239956b64/sepoct2024_f15_monet.jpg)