Collecting the World’s Collections of Small Oddities One Day at a Time

A Q&A with Diana Zlatanovski on how she came to collect collections, what they say about design, and how to be a collector without becoming a hoarder

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121204112033CigaretteHolderTypology_470.jpg)

Diana Zlatanovski is meta. As an anthropologist, a museologist, and a curatorial research associate at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, she spends her days going through collections of art and artifacts, and with her extra time, she takes photos of those collections and many others she finds outside the museum as part of an ongoing project she calls The Typology.

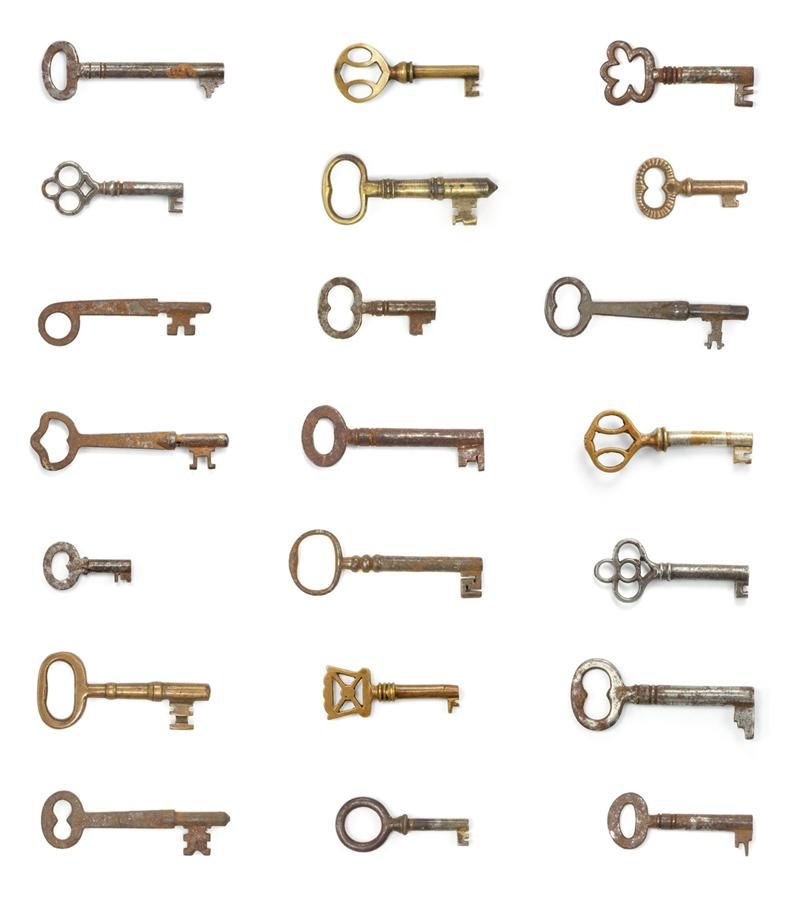

By assembling and examining a grouping of objects with shared attributes, Zlatanovski aims to reveal patterns and information that wouldn’t be visible if looking at each individual piece in isolation. She has gone hunting for these revelations in photos of tools, vegetables, shells, landscapes, portraits, old coins, and much more. We talked with Zlatanovski about how she came to collect collections, what The Typology says about design, and how one gets into her line of work without becoming a hoarder.

At their most fundamental level, collections are accumulations of objects. But they are distinguished by their intentional grouping—a coin collection is different than a handful of change.

Objects are wrapped in meaning, collections are a way for them to tell their common story. A collection makes links and connections between things evident, giving a greater understanding of the story. Only through studying groupings are we able to see a spectrum of variation—information not apparent in isolation can become visible in context.

Was there a particular collection or a particular moment that inspired you to start doing your typology work?

The first object typology I photographed was a collection of wrenches. I didn’t necessarily have a plan for the wrenches when I was collecting them but found myself compelled to acquire them. The varied shapes and sizes, the range of colors in the metal, the texture of the patina, they all conveyed something to me. I began to realize I also had an emotional connection to the wrenches-my father was a builder and tools are objects of memory for me.

As I looked closely at the wrenches they brought to mind archaeological typologies of prehistoric stone tools with their different forms and sizes of grinding and chipping stones. I saw the comparison as an example of the continuity of human ingenuity over time.

Plenty of people collect rocks or stamps or bottles, but you have amazing access to museum archives where you can see assemblages ancient pottery shards, extinct currencies, and primitive tools. Did you have to get permission to start photographing them for your own project? Do you just go into work every day with your camera and shoot the objects you’re sorting through?

Collection storage areas are an endless source of inspiration for me, and I so wish I could spend all of my days roaming through them with my camera! At any given time only a very small percentage of a museum’s holdings are on display so you can imagine the treasure trove of objects waiting in the wings for their day in the spotlight. I am incredibly grateful to get in depth views of museum holdings, it allows me chances for serendipitous discovery.

Different museums have different collection policies, but I do always need to obtain the appropriate permissions to handle and photograph museum artifacts.

Has your method of assembling things ever given you insight into a historical moment or culture that you wouldn’t have otherwise seen? Have any revelations come out of placing objects together and looking at the pattern or the whole?

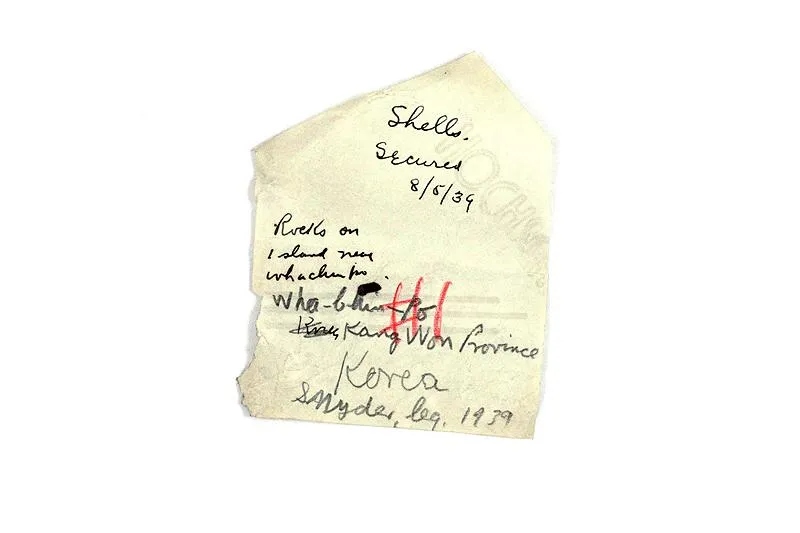

Working with the shell collections at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology teaches me something new every time. What I love about working on the shell typologies is how strikingly similar each shell can seem until I compile all of the specimens into one image and realize how many details are vastly different.

One of the many remarkable things about Harvard’s collections is that they were collected for scientific study, so their documentation adds a whole other layer of interest. I can work with a group of shells that were all collected in a singular moment in time at one specific place, sometimes over a hundred years ago in waters I will likely never visit. Those objects existed together at that place in time and they remain together to this day. These are the connections that make this work so fascinating to me. Objects are what remain behind as a link between their time and ours.

Living in small spaces with a slightly minimalist husband definitely helps keeps my collecting in check. So far, I’ve mostly worked with smaller objects, which can be easily stored or displayed, though I fear the day I’m compelled to do a typology of 19th century sofas. And I suppose one of the benefits of working with museum collections could be that they most definitely won’t let me bring those home!

Does The Typology have an ultimate destination or goal? Is there a point at which you’d feel complete with this project, or a particular assemblage of things that you aspire to capture?

I intend to continue growing Typology and am excited to watch it evolve. New ideas are coming to mind constantly and I’m regularly building on my earlier work. Ultimately my goal is for these collections and their biographies to foster a larger appreciation and interest in the preservation of both cultural as well as natural artifacts. And that will always be an ongoing project.

Since this is a design blog, can you comment on how this is a design project, or what connection you see between Typology and design?

Typology uses logic to convey meaning and influence how we interact with things, which is essentially a design process. A typology creates order within a set of objects much like design distills and simplifies. Both tell stories and create intrigue in a visual medium.

My photographs are visual art so the graphic design and aesthetics of each image is a significant factor. Every typology image is a compilation, I photograph every artifact separately and layout the typology from those separate elements. Visually pleasing patterning has to balance with an arrangement that best conveys the story the objects are telling. Good design is all about that balance.

I would love to include part of the Smithsonian’s collections in Typology in the future. I recently visited an exhibition of art from Kazahkstan at the Freer gallery and I was very intrigued with the collection of ancient daggers on display. The Cooper Hewitt also has a beautiful array of match safes that I would love to photograph. And in homage to Julia Child, it would be great to do a typology of her kitchen tools!

In addition to my own typology photography, I also curate photographic and object typologies that I discover out in the world on my blog, The Typologist. One of my favorite posts was a collection of tags worn by the Smithsonian’s Postal Museum’s mascot Owney, the postal dog.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)