Inside a New Effort to Change What Schools Teach About Native American History

A new curriculum from the American Indian Museum brings greater depth and understanding to the long-misinterpreted history of indigenous culture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/03/05/03054369-945a-48ec-b04d-20a76c2df5d4/middle-school-students-using-nmai-educational-resources_photo-by-alex-jamison.jpg)

Students who learn anything about Native Americans are often only offered the barest minimum: re-enacting the first Thanksgiving, building a California Spanish mission out of sugar cubes or memorizing a flashcard about the Trail of Tears just ahead of the AP U.S. History Test.

Most students across the United States don’t get comprehensive, thoughtful or even accurate education in Native American history and culture. A 2015 study by researchers at Pennsylvania State University found that 87 percent of content taught about Native Americans includes only pre-1900 context. And 27 states did not name an individual Native American in their history standards. “When one looks at the larger picture painted by the quantitative data,” the study’s authors write, “it is easy to argue that the narrative of U.S. history is painfully one sided in its telling of the American narrative, especially with regard to Indigenous Peoples’ experiences.”

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian is setting out to correct this with Native Knowledge 360 Degrees (NK360°). The museum’s national education initiative, first launched in February 2018, builds on more than a decade of work at the museum. The multi-part initiative aims to improve how Native American history and culture is taught in schools across the country by introducing and elevating indigenous perspectives and voices. Just in time for the start of the 2019-2020 school year, the initiative released three new lesson plans, offering a deeper look at the innovations of the Inka Empire, investigating why some treaties between Native American tribes and the U.S. government failed, and providing an in-depth exploration into the context and history of the Cherokee removal in the 1830s.

At the core of NK360° is the “Essential Understandings,” a ten-part framework to help educators think about how they teach Native history. Some of the understandings directly challenge narratives that are already perpetuated in schools through textbooks and standards, such as the idea of American Indians as a monolithic group: “There is no single American Indian culture or language. American Indians are both individuals and members of a tribal group,” the curriculum asserts. Another myth the curriculum addresses is the idea that American Indians are a people of the past: “Today, Native identity is shaped by many complex social, political, historical, and cultural factors.” And it highlights the work done by Native people to foster their cultural identities: “In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, many American Indian communities have sought to revitalize and reclaim their languages and cultures.”

These essential understandings underpin the initiative’s online lesson plans released cost-free, for teachers to use in their classrooms. Edwin Schupman, manager of NK360° and a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, says that the initiative is trying to “meet teachers where they are [and address] what their needs are.”

While the initiative’s staff has extensive plans for subjects they’d like to eventually cover, the lesson plans have, so far, primarily focused expanding on topics already being taught in school—Thanksgiving, treaties between the U.S. government and American Indian nations, the Trail of Tears—so that educators are more likely to use them.

Consider how American Indian Removal is often taught in schools. Students learn that President Andrew Jackson spearheaded the policy and signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. The Act led to the forcible removal of the Cherokee Nation of the modern-day American South, including Georgia and Alabama, to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Thousands of indigenous people died on the journey, hence the name “Trail of Tears.”

But that view obscures that several other tribes were also forced out of their lands around the same time period and that many indigenous people actively resisted their removal. And, for the Cherokee, the arrival in Indian Territory is “where the story usually stops, but it didn’t stop for Native people once they got there,” Schupman says.

NK360°’s newest lesson plan “The Trail of Tears: A Story of Cherokee Removal,” created in collaboration with the Cherokee Nation, offers a more comprehensive view of this often-taught, but not well understood historical chapter. The material brings the history into the present by including Native voices and perspectives. “We have interviews with community members whose families were part of that removal, from leaders of those communities today who are still dealing with effects of nation rebuilding,” says Schupman. The material also complements the previously released lesson plans “American Indian Removal: What Does It Mean to Remove a People?” and “How Did Six Different Native Nations Try to Avoid Removal?”

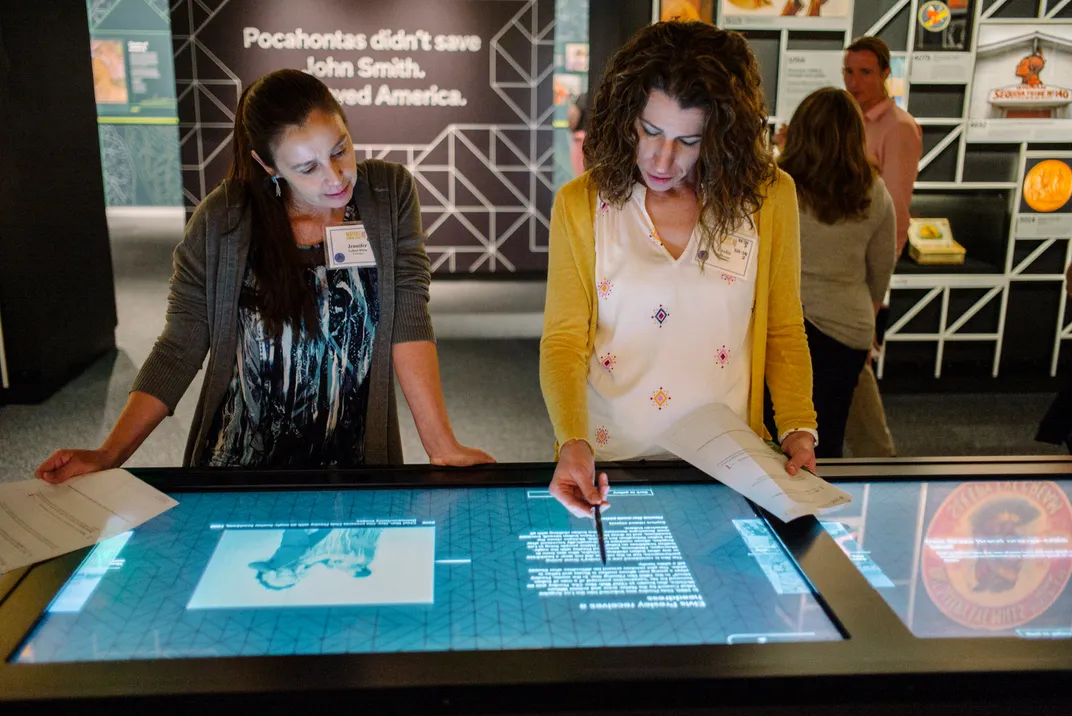

The NK360° lesson plans use inquiry-based teaching to foster critical thinking skills. Schupman says, “you provide questions, give students the primary and secondary sources to analyze, and some activities to do so that they can then gather evidence to answer those questions.” The lessons have interactive elements, like games and text annotation tools, and multimedia elements, including animated videos and interviews with Native American youth, to which students have responded positively, according to a NK360° survey.

Jennifer Bumgarner, a seventh-grade language arts teacher in rural North Carolina, started using elements from “Northern Plains History and Cultures: How Do Native People and Nations Experience Belonging?” in her classroom last year and was excited by how seamlessly they fit into her students’ exploration of community. “The materials are very engaging, very student friendly [and] very easily adapted,” she says.

Sandra Garcia, who teaches social studies to seventh and eighth graders in a dual-language immersion program in Glendale, California, says, “for teachers, it’s very time consuming to gather all these resources.” Garcia adds that she appreciates that NK360° vets, combines and presents the materials in a ready-to-go package.

Both Bumgarner and Garcia attended NK360°’s summer institute for teachers, which is part of a larger, year-round professional development programming. The four-day institute brings about 30 educators from around the country to learn how to better teach Native American history and culture. The experience of learning from the NK360° instructors and collaborating with the other attendees gave Garcia “a lot of confidence to teach the subject matter and to teach others” how to use it and even encouraged her to learn about her family’s own indigenous heritage in Mexico.

This summer Alison Martin arrived from Washington state to be the NK360° 2019 Teacher-in-Residence. Martin, an enrolled descendant of the Karuk tribe, enjoyed the chance to collaborate with the other attending educators—the majority of whom are non-Native and many of whom have little interaction with Native people—on how to better teach this history. “There are well-intentioned teachers who grew up in a system that didn’t teach [about Native Americans] or taught misconceptions. These teachers grow up and have this blindspot,” she says. The museum “is directly addressing this cycle of misconception rooted in decades and centuries of miseducation,” she adds. “It’s easy to relegate Natives as irrelevant, past-tense peoples and it can be hard for teachers who aren’t connected with Native communities to understand what it means to be Native in a contemporary role.”

While at the museum, Martin focused on adapting for fourth graders the high school level curriculum “We Have a Story to Tell: Native Peoples of the Chesapeake Region.” Now that she’s back home and starting her first year as a teacher at a Bureau of Indian Affairs school, and in her tenth year working with kids, Martin plans to test her revised lesson plan in the classroom. Her Native students already have a greater understanding of diversity among indigenous communities, but she’s excited to get them thinking and curious about Native communities across the country, like the Piscataway tribe in the Washington, D.C. region. Martin wants to “make Native education fun and engaging for the kids,” she says. “It should be a celebration of Native communities.”

As it grows, the initiative is drawing on a network of partnerships, from state education offices to Native nations and teacher organizations, to help it develop new curriculum, recruit teachers to its professional development programs and introduce the lesson plans into schools around the country.

More than a year after its launch, Schupman is pleased with the program’s reception. More generally, though, “I think there’s a lot of misunderstanding about the need for more inclusiveness and more equity. That it’s somehow revisionist or threatening to other groups of people,” he says. At its core, NK360° is about Native Americans “telling our own story, our own collective story and doing a much better job of it.”

Understanding Native American history “positions us to better deal with the issues that we face as a nation today,” he says. “If we had a better understanding of other people’s experience with things like immigration or activities like removing people—the impact that they have—I think then we would be less susceptible to inaccurate narratives and more capable of responding in thoughtful ways.”