No Color Photos of Jazz Singer Mildred Bailey Existed… Until Now

An artist shows us that the past was not black-and-white

On January 18, 1944, the Metropolitan Opera House rocked to a sound it had never heard before. In the words of a reporter in attendance, “a 10-piece all-star swing band...shook the august walls with its hot licks and about 3,400 alligators”—jazz fans—“beat it out through every number.” The Esquire All-American Jazz Concert was a far cry from the venue’s usual fare. “Just picture swinging shoulders, cat-calls, squeals, screeching whistles and a rhythmic tattoo of hands while Sir Thomas Beecham was conducting, say, Rigoletto,” the reporter wrote.

Appearing that night 75 years ago were some of the greatest jazz musicians in history. Benny Goodman played a number live from Los Angeles via radio link, while Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday and Mildred Bailey—pictured here—took the stage. Bailey, a fixture in New York’s hottest jazz clubs, is less well-remembered today than her contemporaries, but a poll of leading music writers around the time of the Opera House concert ranked her as the second-best female jazz singer in the world, just behind Holiday. Although no longer in perfect health—she suffered from diabetes and had been hospitalized for pneumonia the previous year—Bailey still belonged among the musical elite, as her friends and fellow stars Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra recognized. At the Met, ”Mrs. Swing” thrilled the crowd with her signature “Rockin’ Chair.”

Gjon Mili, the great Albanian-American photographer whose work was made famous in Life magazine, captured the event. One of Mili’s photographs shows Bailey rehearsing backstage, accompanied by Roy Eldridge on trumpet and Jack Teagarden on trombone. The original image was shot in black-and-white; this new version has been created for Smithsonian by the digital artist Marina Amaral, who uses Photoshop to add colors to historical pictures. Amaral, 24, has colorized hundreds of photographs, with the aim of giving a new perspective on the past.

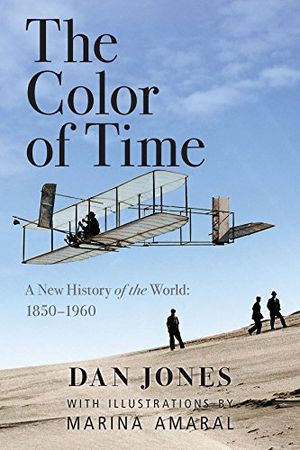

The Color of Time: A New History of the World: 1850-1960

The Color of Time spans more than one hundred years of world history―from the reign of Queen Victoria and the American Civil War to the Cuban Missile Crisis and the beginning of the Space Age. It charts the rise and fall of empires, the achievements of science, industrial developments, the arts, the tragedies of war, the politics of peace, and the lives of men and women who made history.

Color affects human beings in powerful ways. For at least 200 years scientists have proposed links between different colors and emotional responses—for example, red elicits feelings of excitement, and blue, feelings of relaxation. Recent studies have suggested that we are acutely sensitive to small variations in the hues of others’ faces; exposure to different colors has also been shown to affect our moods, choices, appetites and intellectual performance. Exactly why has not been adequately evaluated. But the popular response to work by Amaral and to projects such as Smithsonian Channel’s America in Color, which features colorized film clips, shows that the technique can deepen the connection viewers feel with historical figures and events.

“Colorizing photographs is a process that requires a combination of careful factual research and historical imagination,” says Amaral, a former international relations student who now works full-time on historical images from her home in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Amaral is often drawn to a photo by the small details—like the tendrils of smoke from an onlooker’s cigarette—but says she always looks for “an image that allows me to tell a broader story.” Here her main task was to create a new portrait of Bailey that was sensitive to her family heritage, which was unusual for the jazz scene at a time when many of the most famous musicians were black. Bailey, by contrast, was raised by her mother, a Coeur d’Alene tribal member, on the Coeur d’Alene reservation in Idaho, although Bailey was often perceived as white in an era when Native Americans suffered widespread discrimination. This made colorizing a challenge.

There are no known color photographs of Bailey and the original image doesn’t provide many clues, so Amaral looked for scraps of information in sources describing Bailey. She also turned to the color portrait of Bailey done by Howard Koslow for a 1994 U.S. postage stamp, though that portrait, also based on a black-and-white photograph, wasn’t conclusive.

Amaral is careful to point out that her works are not about restoration, but about interpretation. “They are as much about encouraging questions about past events as depicting them objectively.” What isn’t in doubt is the ability of color to transform the way we understand even the most familiar sights. As Bailey herself once sang: “I used to be color-blind, but I met you and now I find there’s green in the grass, there’s gold in the moon, there’s blue in the skies.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.