Contemporary Aboriginal Art

Rare artworks from an unsurpassed collection evoke the inner lives and secret rites of Australia’s indigenous people

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Aboriginal-Art-631.jpg)

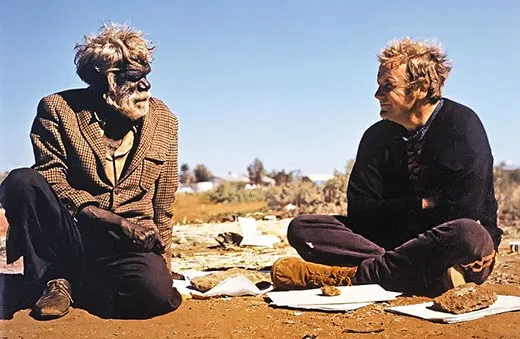

An art movement’s origins usually can’t be pinpointed, but boldly patterned Aboriginal acrylic painting first appeared at a specific time and place. In July 1971, an art teacher named Geoffrey Bardon distributed some brushes, paints and other materials to a group of Aboriginal men in the forlorn resettlement community of Papunya, 160 miles from the nearest town, Alice Springs. Bardon had moved near the remote Western Desert from cosmopolitan Sydney hoping to preserve an ancient aboriginal culture imperiled by the uprooting of Aboriginal people from their traditional territories in the 1950s and ‘60s. The men, who saw Bardon distributing the art supplies to schoolchildren, had a simpler aim: they were looking for something to do. Together they painted a mural on a whitewashed schoolhouse wall, and then they created individual works in a former military hangar that Bardon called the Great Painting Room. In 1972, with his assistance, 11 of the men formed a cooperative called Papunya Tula Artists. By 1974 the group had grown to 40.

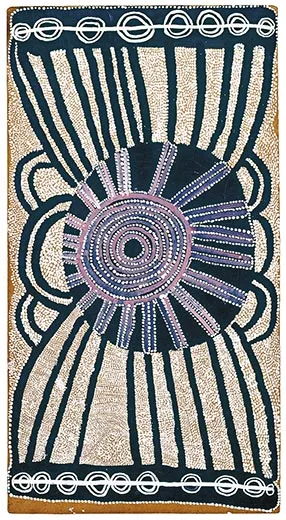

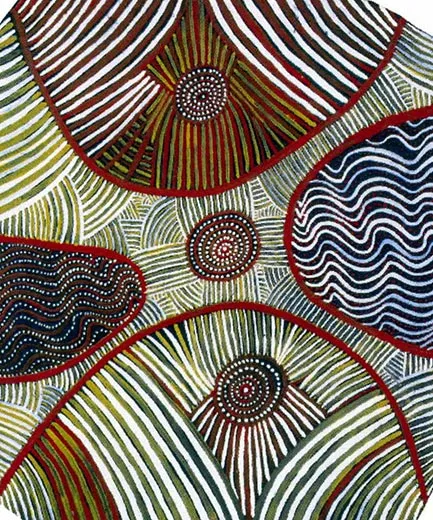

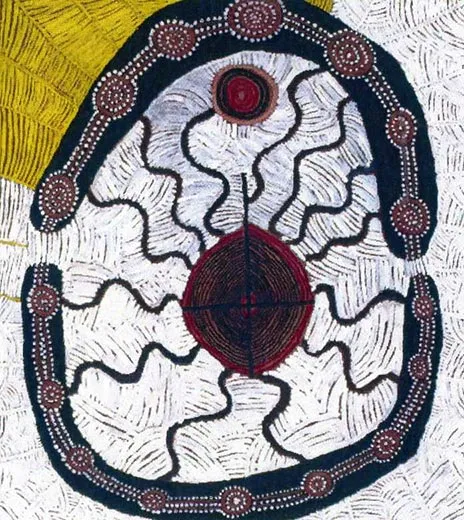

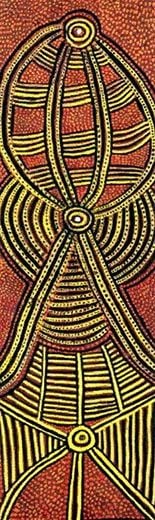

Papunya Tula is now one of about 60 Aboriginal arts cooperatives, and Australian Aboriginal art generates nearly $200 million in annual revenues. It is not only the largest source of income for Aboriginal people but also, arguably, the most prestigious Australian contemporary art. Featuring bold geometric designs in earth tones, with characteristic circles, dots and wavy snakelike lines, Aboriginal acrylic painting appeals to Western collectors of both abstract and folk art. Prices have soared. A mural-size 1977 painting on canvas by the Papunya artist Clifford Possum established a record price for the genre when it sold in 2007 for $1.1 million.

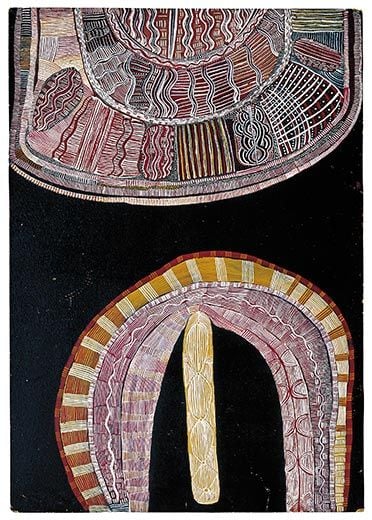

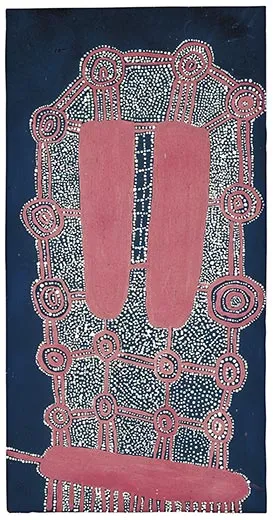

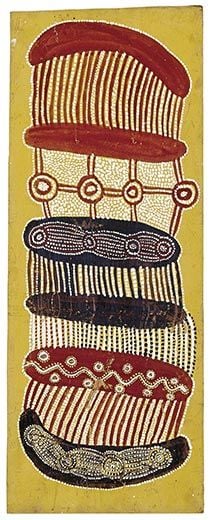

Still, a special aura attaches to the first, small paintings, done on masonite boards usually less than 2 by 3 feet. Created before there was commercial interest, they benefit from the perception that they are more “authentic” than the stretched-canvas works that came later. It is hard to deny the energy and inventiveness of the early boards; artists used unfamiliar tools and materials to cover two-dimensional surfaces with designs they’d employed in ritualistic body painting or sand mosaics. They improvised, applying paint with a twig or the tip of a paintbrush’s wooden handle. “The early period—you’re never going to find anyplace where there’s so much experimentation,” says Fred Myers, a New York University anthropologist. “They had to figure everything out. There’s an energy that the early paintings have, because there’s so much excess to compress.”

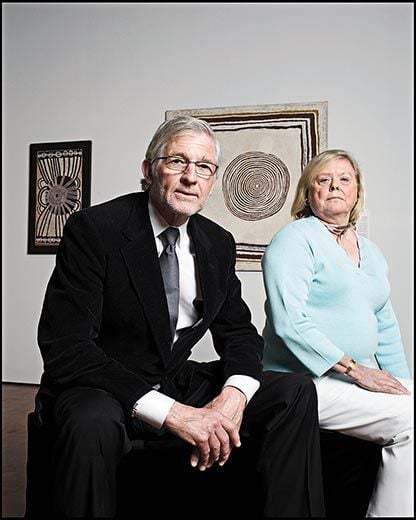

The first exhibition in the United States to focus on these seminal works—49 paintings, most of them early Papunya boards—recently appeared at New York University, following showings at Cornell University and the University of California at Los Angeles. The paintings are owned by John Wilkerson, a New York City-based venture capitalist in the medical field, and his wife, Barbara, a former plant physiologist. The Wilkersons collect early American folk art and first became enamored of Aboriginal work when they visited Australia in 1994. “We both thought, ‘We don’t like this—we love it,’” Barbara recalls. “We just liked everything.” With the help of a Melbourne-based gallery owner, they soon concentrated on the earliest paintings.

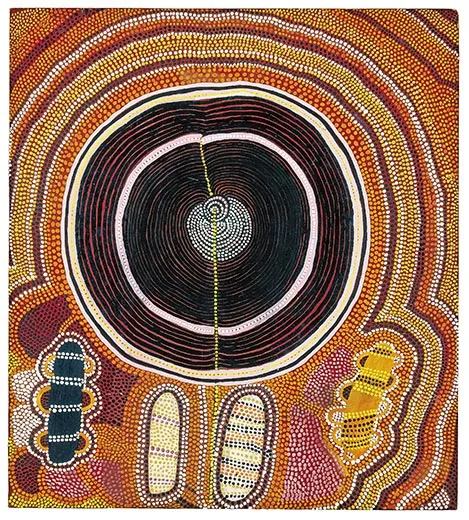

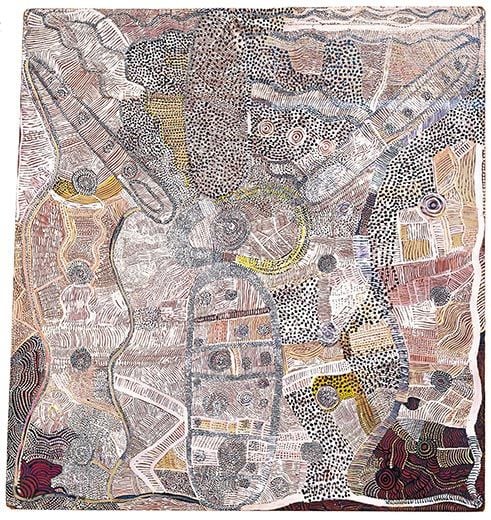

The Wilkersons’ costliest board was the 1972 painting Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa, a dazzling patchwork of stippled, dotted and crosshatched shapes, bought in 2000 for some $220,000—more than twice the price it had been auctioned for only three years earlier. The painting was done by Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, an original member of the Papunya cooperative and one of its most celebrated. Sadly, the artist himself had long been overlooked; in 1997, an Australian journalist found Warangkula, by then old and homeless, sleeping along with other Aboriginal people in a dry riverbed near Alice Springs. Though he reportedly received less than $150 for his best-known painting, the publicity surrounding the 1997 sale revived his career somewhat and he soon resumed painting. Warangkula died in a nursing home in 2001.

Though the Aboriginal art movement launched in Papunya is just four decades old, it’s possible to discern four periods. In the first, which lasted barely a year, sacred practices and ritual objects were often depicted in a representational style. That was dangerous: certain rituals, songs and religious objects are strictly off limits to women and uninitiated boys. In August 1972, an angry dispute broke out at an exhibition in the aboriginal community of Yuendumu over explicit renderings in Papunya paintings. Some community members were offended by the realistic depictions of a wooden paddle swung in the air to produce a whirring sound in initiation ceremonies that are hidden from women and children.

In response to the furor, artists began to avoid forbidden images or conceal them under dotting, stippling and cross-hatches. So began the next period. A forerunner of that style, painted around August 1972, is Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa, in which Warangkula’s elaborate veilings acquire a mesmerizing beauty that relates to the symbolic theme of raindrops bringing forth the vegetation stirring below the earth.

”I think the older men love playing with almost showing you,” Myers says. It’s not just a game. These paintings mirror traditional ritual practice; for example, in one initiation ceremony, adolescent boys whose bodies are painted in geometric or dotted patterns appear before women at night through a scrim of smoke, so the designs can be glimpsed but not seen clearly. “You have people who already have a tradition of working with concealment and revelation,” Myers says.

In the third period, the art found a commercial market with acclaimed, large-scale canvases in the 1980s. And the fourth period, roughly from the 1990s to the present, includes lower-quality commercial paintings—disparaged by some art dealers as “dots for dollars”—that slake the tourist demand for souvenirs. Some painters today lay down geometric, Aboriginal-style markings without any underlying secret to disguise. (There have even been cases of fake Aboriginal art produced by backpackers.)

Still, much fine work continues to be produced. “I’m very optimistic, because I think it’s amazing that it has lasted as long as it has,” Myers says. Roger Benjamin, a University of Sydney art historian who curated the exhibition, “Icons of the Desert,” says gloomy predictions of the late ‘80s have not been borne out: “Fewer and fewer of the original artists were painting, and people thought the movement was dying out. That didn’t happen.”

One striking change is that many Aboriginal painters today are women, who have their own stories and traditions to recount. “The women painting in Papunya Tula now tend to use stronger colors and—especially the older ladies—are less meticulous,” Benjamin says.

Though seemingly abstract, the multilayered paintings reflect the Aboriginal experience of reading the veiled secrets of the hostile desert—divining underground water and predicting where plants will reappear in the spring. According to Aboriginal mythology, the desert has been marked by the movements of legendary ancestors—the wanderings known as Dreamings—and an initiate can recall the ancestral stories by studying and decoding the terrain. “In the bush, when you see somebody making a painting, they often break into song,” Benjamin says. They’re singing the Dreaming stories in their paintings.

The Wilkersons’ original plan to exhibit paintings in Australian museums fell through after curators feared that Aboriginal women or boys might be exposed to sacred imagery. Aboriginal community members also decreed that nine reproductions could not be included in the exhibition catalog. (The American edition contains a supplement with the banned images. Smithsonian was not granted the right to publish any of them.)

While Western art collectors may value the works according to how well they were executed, Aboriginal people tend to rank them by the importance of the Dreaming in them. “White people can’t understand our painting, they just see a ‘pretty picture,’ “ the Papunya artist Michael Tjakamarra Nelson once remarked.

Some of the imagery in the exhibition is comprehensible to informed outsiders, while some is ambiguous or completely opaque. For many Western spectators, the secret religious content of the paintings—including, in the early boards, images said to be fatal to uninitiated Aboriginal people—only adds to their appeal. Like much geometrically ordered art, Aboriginal painting is beautiful. Tantalizingly, it also exudes mystery and danger.

New York City-based freelance journalist Arthur Lubow last wrote for Smithsonian about China’s terra cotta soldiers.