Costume’s Cultural Reveal

The Los Angeles County Museum aims to draw new visitors and historic insights with a landmark costume acquisition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/womans-four-piece-ball-gown-631.jpg)

One day an art conservator was studying a 19th-century French portrait at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art when Sharon Takeda happened to walk by. He was puzzling over a section of the painting, the man’s lush emerald cloak. Takeda, the museum’s costume and textile department head, knew immediately what the restoration expert was staring at: the artist’s rendering of “changeable silk,” an iridescent fabric that changes color depending on the light. Thanks to Takeda¬--a curator who surely knows her warp from her weft--the conservator learned what the fabric should look like after cleaning.

Such moments are rare in art museums, where "costume and textiles have always been kind of the poor cousin or the oddity," says Takeda, who has yet another reason these days to be proud of her chosen field: The museum, known as LACMA, has just acquired a massive collection of historic European fashions and accessories. The rare trove—including a four-piece silk taffeta ball gown, a boy's frock of embroidered cashmere silk and a women's cage crinoline petticoat—will go on exhibit in 2010, allowing Hollywood costume designers, researchers and the public to see apparel of meticulous construction and artistic design that make today's fashion articles look like shmattes.

“It is one of the biggest highlights in the history of this collection in terms of quantity and quality and value,” says Takeda, who traveled to a warehouse in Switzerland to view the items before purchase.

The museum announced the purchase earlier this year, three years after LACMA director Michael Govan had challenged his curators to locate "museum-altering" acquisitions. It just so happened that two prominent dealers had just combined their historic costume collections to sell in Basel.

The museum does not disclose exact figures but said the entire collection cost several million dollars, an attractive price considering that one sculpture by Richard Serra would cost $10 million and that costume exhibits draw lots of visitors to museums.

The esteemed Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City continually mounts crowd-pleasing exhibitions. In 2006 its "Anglomania," about modern British fashion, drew more than 350,000 people in four months. From May 6 to August 9, 2009, the institute will stage "The Model as Muse: Embodying Fashion." In Washington, D.C., the first ladies' inaugural gowns have long been one of the Smithsonian Institution's most popular collections. At the renovated National Museum of American History, a gallery showcases 14 gowns with related artifacts.

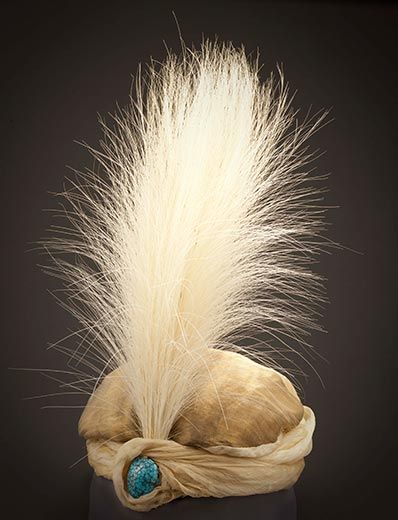

The LACMA collection, dating from 1700 to 1915, contains 250 examples of men's, women's and children's dress and more than 300 accessories, such as shoes, purses, hats, shawls, fans and undergarment. A women's turban sports long egret feathers. A hunting ensemble circa 1830 teams a red wool jacket with white leather beeches. Sumptuous women's outfits, which were essentially moveable displays of wealth, will be shown next to elaborate understructures that created the stylish women's shape of the era.

“Costumes are, of course, beautiful things,” says Takeda. “But there is also a lot that the object speaks to, whether it's textiles and trade, the economic makeup of a country, whether it's the fashionable silhouette, which may have to do with, for example, the big 18th-century pannier silks, with yards and yards of fabric showing that you could afford these incredibly expensive silks.”

In contrast to the museum's "lobster-pot" bustle and bizarre pannier, which puffed out a woman’s skirt several feet beyond both hips, the collection also contains an early-20th-century unstructured brassiere with a delicate appliqué of blue flower petals. France’s Paul Poiret designed it for his wife and muse, Denise. “Arguably, he is the designer who helped do away with the corset,” Takeda says. “He made such a dramatic shift in that day.”

Another article of clothing, a men's knitted waistcoat from the French Revolution era of the 1790s, could be considered a precursor of today's political T-shirt. Its lapel features the motif of a butterfly having its wings clipped by nearby scissors. "Women did the knitting and women were also a big part of the start of the revolution... It's about not dressing like a royalist," Takeda says.

The collection, bought with funds from philanthropist Suzanne Saperstein and other donors, came from Martin Kamer and Wolfgang Ruf. "One from London, one from Switzerland. They had been in the business 25 years. Both had their own private collections. They had been rivals before," Takeda says.

“Everything was in good to very good condition, she says. “It was kind of a no-brainer in terms of trying to pursue it.”