The Court Case That Inspired the Gilded Age’s #MeToo Moment

A turn-of-the-century trial, the focus of a new book, took aim at the Victorian double standard

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/4a/ba4a159e-4228-47f7-9973-f7a30d156e7c/pollard-breckenridge.jpg)

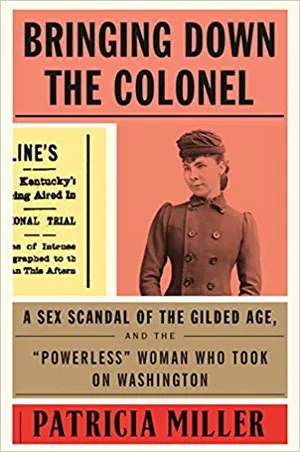

For five weeks in the spring of 1894, a scandalous trial captured Americans’ attention. Crowds formed outside the courthouse, and across the country, readers followed the story in their local newspapers. Madeline Pollard, a woman with little social standing, had sued congressman William C. P. Breckinridge of Kentucky with a “breach of promise” suit that claimed damages of $50,000. As with similar suits filed at the time, Pollard sought compensation for her former lover’s unwillingness to wed, but this case, the subject of journalist Patricia Miller’s new book Bringing Down the Colonel, was different.

Pollard was determined to challenge the different standards set out for men and women. “As chastity became central to the definition of a respectable woman in the nineteenth century, women found it was their sexual conduct, not the actions of men, that was really on trial,” writes Miller.

During her testimony, she recounted a nun admonishing her decision to sue: “‘Why on earth do you want to ruin that poor old man in his old age?’” But she implored the nun, and the jury, to see it from her point of view: “I asked her why should that poor old man have wanted to ruin me in my youth?”

Against the odds, Pollard won her case and, Miller argues, helped usher the “transition to a more realistic sexual ethic that flowered in the twentieth century.” Although Pollard chipped away at the sexual double standard, recent news makes clear that women’s behavior is still judged more harshly than men’s. Miller spoke with Smithsonian about her timely assessment of the Breckinridge-Pollard case.

How was Madeline Pollard’s court case unusual?

Pollard sued Congressman William Breckinridge for breach of promise. Such suits were not uncommon. They recognized that marriage was women’s primary career in those days, that was a real financial hardship if you had kind of aged out of the desirable marriage age.

But these suits were designed to protect the reputation of respectable women. What was revolutionary was that Pollard admitted she was a “fallen” woman. She had been Breckinridge’s longtime mistress, and when his wife died, he did not marry her as he had promised. In those days, if a woman was “fallen,” she was a social pariah. She couldn’t get a respectable job or live in a respectable home. And she could certainly never make a respectable marriage.

Pollard's case struck at the heart of the Victorian double standard. What did that standard dictate?

It was a society where women were viciously punished for having sex when they weren't married, but men, even a married man like Breckinridge, were encouraged to sow their wild oats. There was this class of women, the Madeline Pollards of the world, who were just ruined women. They were just women who you did that with. That was a separate class of people, and that's how people not only differentiated between good woman and bad woman, but also protected a good woman. You protected moral, upstanding wives and fiancés by having this class of ruined, kind of “polluted” woman that men like Breckinridge could go off with.

Why was 1894 the right time for a lawsuit like this?

This was a period when we saw a tremendous influx of women into the work force. It really made society question the idea that good women are good because they stay at home, and that’s how we protect them. We keep them in the domestic sphere, and women who go out into the public world, well they take their chances. When women start moving into the public sphere, society needed to rethink men like Breckinridge.

At first, the newspapers asked, “Is it blackmail?” But then women started to speak up for her. Breckinridge was older, he was married, he was in a position of power over this young woman—suddenly he was seen as the predator, instead of the woman being seen as trying to corrupt the good husband. By the end of the trial, both men and women broadly approved of the verdict in Pollard’s favor.

You wrote that Pollard’s case revealed a certain shadow system. Can you briefly describe the system and its effect?

Over the course of telling her story, she really clued people in on how men like Breckinridge were able to get away with having a mistress. When Pollard was pregnant the first time, she goes into a lying-in home, a type of charity home that basically took unwed mothers and kept them off the streets and out of sight till they gave birth. Then [their] children were put in what were called orphan asylums those days. Illegitimate children would be put in these homes, where in some cases they perish in their first year of life because they were just kind of abandoned. When she goes to the House of Mercy, it’s a home for fallen women because they had no way to make a living.

Some women could be committed to those places by their families or by the justice system. There was a kind of semi-informal penal system and charity system that existed to hide these women who were debauched by these powerful men, basically. The most damning revelation comes when Pollard talks about the two children she has, both of whom she says Breckinridge compelled her to leave in these infant asylums, and both of whom died.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/8e/c98e64d3-25ab-4bd1-b06d-e751236472d4/nov2018_b14_prologue.jpg)

You wove two other women's stories in the book throughout. Briefly, who were Nisba and Jennie, and why are their experiences important to understanding Madeline's?

Nisba was Breckinridge’s daughter. She was important to understand because she was on the cutting edge of women who wanted a professional career. Her family had a long history of being in politics. Her great-grandfather, John Breckinridge, had been Thomas Jefferson's Attorney General. Her father was a famous congressman and lawyer, and she wanted to be a lawyer.

There were only 200 women lawyers in the country at the time. It was so hard for women to break into the profession, because most states wouldn't even admit women into the bar. They said, “Well, women just clearly cannot be lawyers. We just won't admit them to the bar.” It was a self-reinforcing logic that even if you went to law school, even if you could pass a bar exam, many states just refused to decide women could be lawyers because it was just too disreputable for a woman to be in a courtroom dealing with these breach of promise cases and illegitimacy cases. She was wealthy, she had a great education, she still couldn't get a foothold into the law.

Jennie is the flip side of the coin. Jennie Tucker was a young secretary from a formerly prominent mercantile family in Maine that had fallen, like many families, on hard times. So, she was required to go and get a job. She went to secretarial school. She got herself a job. Even then, she just struggled. Women were still kept at the lowest levels of work even though they were needed at clerical work, they were still kept basically at kind of starvation wages. They could work, but they could barely make a living.

She eventually is hired by Breckinridge's lawyer to spy on Madeline in the home for fallen women. So, that's why her story gets wound into it, but I think it's important to show in both kind of the secretarial classes, the clerical class and the professional class, women had such a struggle at this time to break into the real world where they could be self-supporting individuals.

I felt that their stories were as important to understanding the times that Madeline Pollard was in, as her story was, really.

Did Pollard get a fair trial?

She did, which is kind of surprising and just points to a sea change in attitudes. I talk about a case barely 15 years earlier where the woman was practically laughed out of court for filing a similar lawsuit. She had letters that attested that a former senator had promised to marry her. Even with evidence, it was just obvious from the get-go that the judge did not take the claim seriously, that the court thought it was distasteful to even have to listen to this suit. When he gave the jury charge to the jury, it became legendary in Washington legal circles because he said, “Gentleman of the jury, take this case and dispose of it.” That was his entire instruction to the jury. That just showed how quickly attitudes changed and that they took Pollard seriously.

It was also partly because she had really good lawyers who were very well respected in the legal establishment. To have two such well respected lawyers willing to bring this case, that really shook people up. They thought, “Well, these guys would not take this if they did not think this was a good case.”

What were the social repercussions of the case?

Pollard demanded the sexual morality of men and women be judged the same way. Of course, you still see remnants of the Victorian double standard today, but Pollard and her compatriots helped create a new world for women, just as the women speaking up in the #MeToo movement are. It often takes one brave woman to say, “I’m not going to be shamed.” Pollard assumed she was going to be shunned by society. She knew what she was sacrificing, but she refused to be shamed. And after the trial, a lot of well-off women took her under their wing. She lived abroad, traveling all over. It was a very adventurous, interesting life.