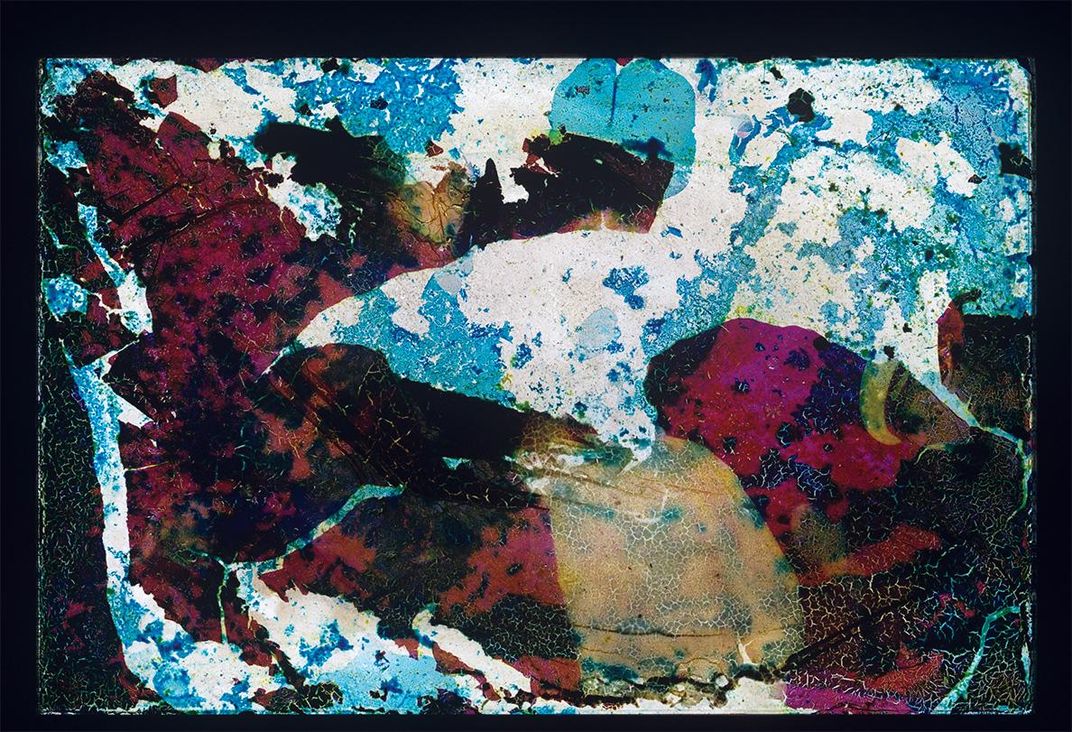

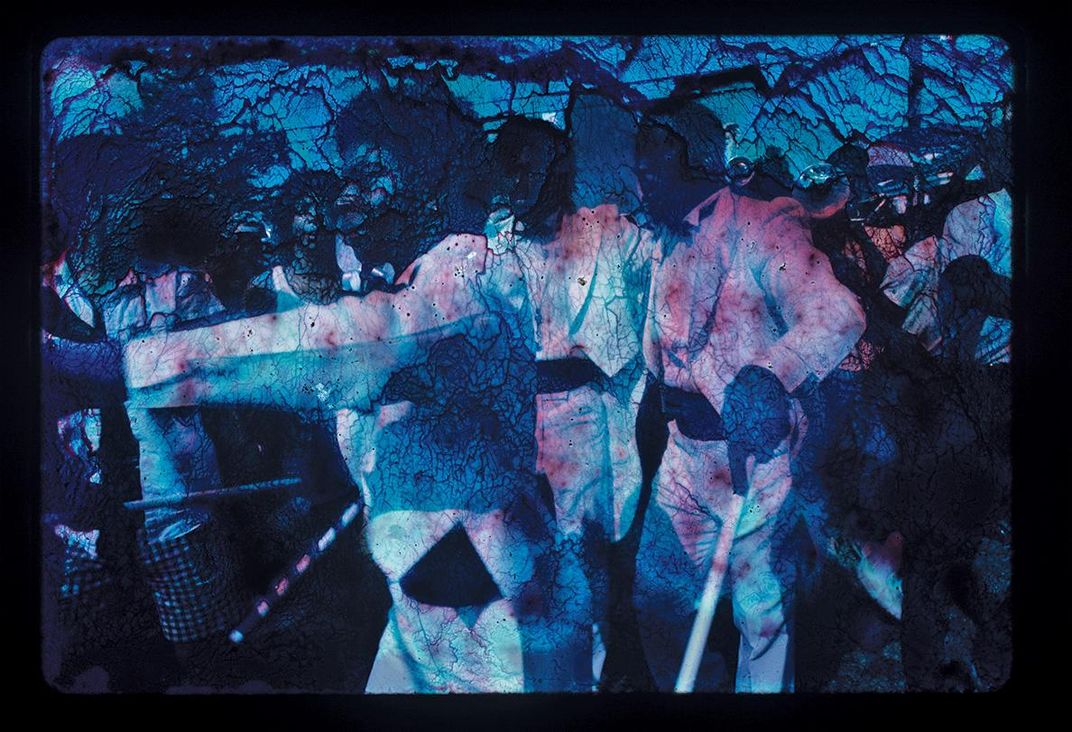

Hurricane Katrina was bearing down on New Orleans, so Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun packed their photography archive—thousands of slides, negatives and prints the couple had amassed over three decades documenting African American life in Louisiana. They filled a dozen plastic bins, which they stacked high on tables. Then they drove to Houston with their two children, planning to be gone for maybe two weeks. Ten weeks later, McCormick and Calhoun returned home to...devastation. “All there was, was waterlogged,” Calhoun says. “Imagine the smell—all that stuff had been in that mud and mold.” They figured they had lost everything, including the archive, but their teenage son urged them not to throw it away. They put the archive into a freezer, to prevent further deterioration. With an electronic scanner they copied and enlarged the images—at first just searching for anything recognizable. The water, heat and mold had blended colors, creating surreal patterns over ghostly scenes of brass band parades, Mardi Gras celebrations and riverside baptisms. “Mother Nature went way beyond my imagination as a photographer,” Calhoun says of the otherworldly images. McCormick says, “We no longer consider them damaged.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/e6/8ce660c9-3f47-4282-8c37-3ca325ff6a34/keith-calhou_chandra-mccormick_photo-by-adrienne-battistella.jpg)

Today McCormick and Calhoun’s altered photographs are viewed as a metaphor for the city’s resilience. Yet they’re also a memento of a community that is no longer the same. By 2019, New Orleans had lost more than a quarter of its African American population. “So much is vanishing now,” Calhoun says. “I think this work serves as a record to validate that we once lived in this city. We were its spiritual backbone.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/32/cf321e5b-25ac-4524-bacf-6c1add606587/social-crescent-city.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/c7/74c776bb-33d9-4d11-a6f8-1e2dd65219bc/julaug2021_g01_new_orleans.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)