Debating Louis Castro

Was he the first foreign-born Hispanic in the Major Leagues?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/luis-castro-388.jpg)

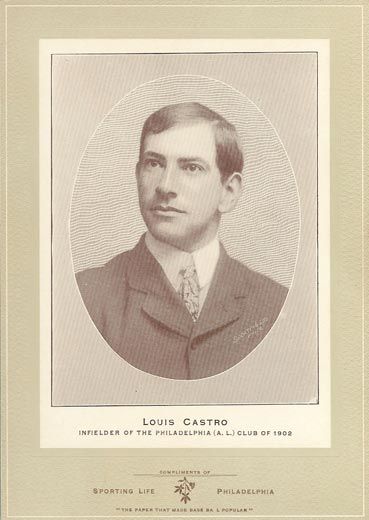

A quick glance at baseball's record books reveals nothing special about Louis Castro. His official file says he was born in 1876 in New York City and shows that he played 42 games as a second baseman for the Philadelphia Athletics during the 1902 season. He batted .245 that year with one home run and 15 runs batted in, then bounced around the minor leagues. He died in New York in 1941.

At a glance, Castro was just another one-season role player from baseball's early days. Yet many baseball historians are interested in his brief, unremarkable career. Dick Beverage, president of the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR), describes Castro's story as "a mystery." Gilberto Garcia, who recently finished a biography of Castro for the baseball journal Nine, says Castro is "part of American folklore." And baseball writer Leonte Landino calls Castro "a mystical, mysterious, even phantasmagorical figure."

So why all the mystery surrounding someone who appears to have had little to no impact on the game of baseball? The answer lies in the most basic of details: Castro's birthplace.

Until 2001, Castro was listed in the official records as being born in Medellin, Colombia—not New York City. That would make Castro the first foreign-born Hispanic to play Major League ball. That's a prestigious historical role, considering that at the start of the 2007 season, nearly 25 percent of Major League Baseball's players were from Mexico, South America or the Caribbean.

"He was the first one," says Nick Martinez, a baseball researcher and Castro biographer who runs louiscastro.com, a Web site dedicated to getting Castro a tombstone indicating he was the first Hispanic in the major leagues. "He laid the stake and made it easer for everyone else who is Latin to come in and play the game of baseball."

To be clear, Castro was no Jackie Robinson in terms of talent or cultural impact. When Castro broke into the major leagues in 1902, there was little fanfare surrounding his signing, and he didn’t have to deal with the animosity that was directed at Robinson every day of the 1947 season. Why? He looked white—or, at least, not black.

"The only issue they [Major League Baseball] had at that time was if it was a Negro player," Landino says. "Castro was a white player. Even though he was a Latino, he was white, and they didn’t have any problem with that."

The baseball portion of Castro's story begins at Manhattan College, where he was a pitcher and a utility infielder near the turn of the century. Manhattan College regularly played exhibition games against the New York Giants, and after college Castro played a couple years for semi-pro teams. Somewhere along the line, Philadelphia manager Connie Mack saw the young prospect.

Of course, sometimes prospects don't work out. Napoleon Lajoie, who had played second base for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1901, was ruled ineligible to return to the team early the following season, for contractual reasons. Castro filled in serviceably for 42 games in 1902, but he was not Lajoie—a future Hall of Famer who, in his first year with the A's, had batted .426, the fourth-highest single-season average in baseball history.

That left Castro with some big shoes to fill. "Ultimately, I think the shoes won out—because he only played that one season with the Athletics," says Adrian Burgos, author of Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line.

Despite winning the American League pennant in 1902, the Athletics did not retain Castro. He played in the Pacific Coast League and the South Atlantic League, and even managed the Augusta Tourists for a few seasons. Late in his life, he moved back to New York and lived with his wife until he died at age 64.

Through 1910, all the documents surrounding Castro's life—Manhattan College records, newspaper articles from his playing days and the form he filled out for the 1910 census—describe Castro as being from Colombia. There was no reason to question that fact until 2001, when Beverage came across Castro's file at the Association of Professional Ball Players of America. Castro, who was apparently quite poor at the end of his life, had joined the association in 1937 and received financial assistance from the organization in the final year of his life, Beverage says. Castro's file lists his place of birth as New York City, and that—coupled with his death certificate and his 1930 census form, both of which list Castro's birthplace as New York—was enough to convince SABR's biographical committee to change his birthplace to New York.

No one knows why the forms say different things. Garcia found a ship's log that lists a Louis Castro as an American citizen, so it could be that Castro learned at some point during his life that he was actually born in New York. Or perhaps a middle-aged Castro feared getting deported, or thought he could get more financial assistance by being an American citizen. Whatever the reason, that little switch of information has caused baseball researchers much angst over the years.

Martinez, however, thinks he has it figured out. Recently, he found a list of passengers from the S.S. Colon, which arrived in New York in 1885. The list includes an eight-year-old boy, Master Louis Castro, as well as another Castro with the first initial "N," which might have referred to Nestor, Louis' father. Though Major League Baseball still lists Castro as being from New York, the ship's log was enough to convince Martinez and Landino that Castro was indeed the first foreign-born Hispanic to play in the major leagues. Even the skeptical Beverage now says, "My thinking has sort of changed. It’s conceivable that he was born in New York, but I’m beginning to think that he was born in Colombia."

Even if Castro was indeed Colombian, many say the identity of the first Hispanic ballplayer is still up for debate. Some say that Esteban Bellan, a native-born Cuban who played with the Troy Haymakers of the National Association in 1871, should be acknowledged as the first Hispanic to play professional baseball. Jim Graham, director of the Baseball Hall of Fame library agrees: "Bellan did play at the highest level of the game that existed in 1871, so we usually throw the nod in his direction." Others point to Vincent Irwin "Sandy" Nava, who was born in San Francisco but described his mother as being from Mexico. Nava played for the Providence Grays in the 1880s.

But the Elias Sports Bureau does not consider the National Association an official major league, which would eliminate Bellan, and Martinez argues that Nava's birthplace rules him out as well.

Using that logic, Castro would indeed be the first of many Hispanics to play in the major leagues. And even though he might not have been harassed the way Jackie Robinson was in his day, he did open doors—perhaps even for Robinson. Branch Rickey, who eventually signed Robinson to the Dodgers, saw Castro as an early example of integration in the Major Leagues, Burgos says.

"I think it’s a big part of what you saw teams do throughout the 1930s and early '40s," Burgos says. "They continued to push the limits of what was the exclusionary point along the color line."

Ian Herbert covers sports for the Washington Post Express.

Corrections appended, October 19, 2007: Originally this article contained several errors about Napoleon Lajoie's time with the Philadelphia Athletics. Lajoie spent five years with the Philadelphia team in the National League before joining the American League's Athletics in 1901. The article said Castro was sent down to the farm system in 1902; he was not retained by the team. The article also said a list of passengers from the S.S. Colon included "Nestor Castro." It actually included "N. Castro," which could have been Nestor, Louis Castro's father.