Dennis the Menace Has an Evil British Twin

Meet the lovable American cartoon character’s sinister counterpart

They were born simultaneously, in March 1951, two entirely independent and wildly contrasting Dennis the Menaces. One was the creation of Hank Ketcham, a former Disney animator in California. The other was the brainchild of the British cartoonist David “Davey” Law. Neither had any knowledge of the other’s Dennis until both debuted in the same week—Ketcham’s in the funny pages of 16 U.S. newspapers and Law’s in the venerable and anarchic British weekly The Beano. Each Dennis would carry on for decades, spawning TV shows and theme-park attractions.

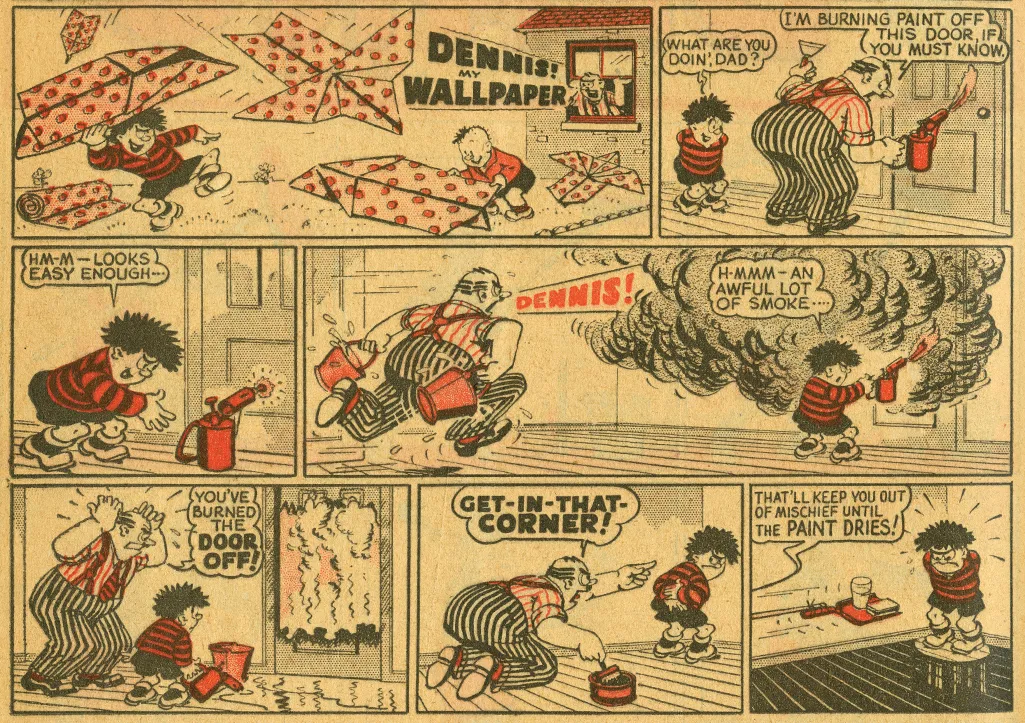

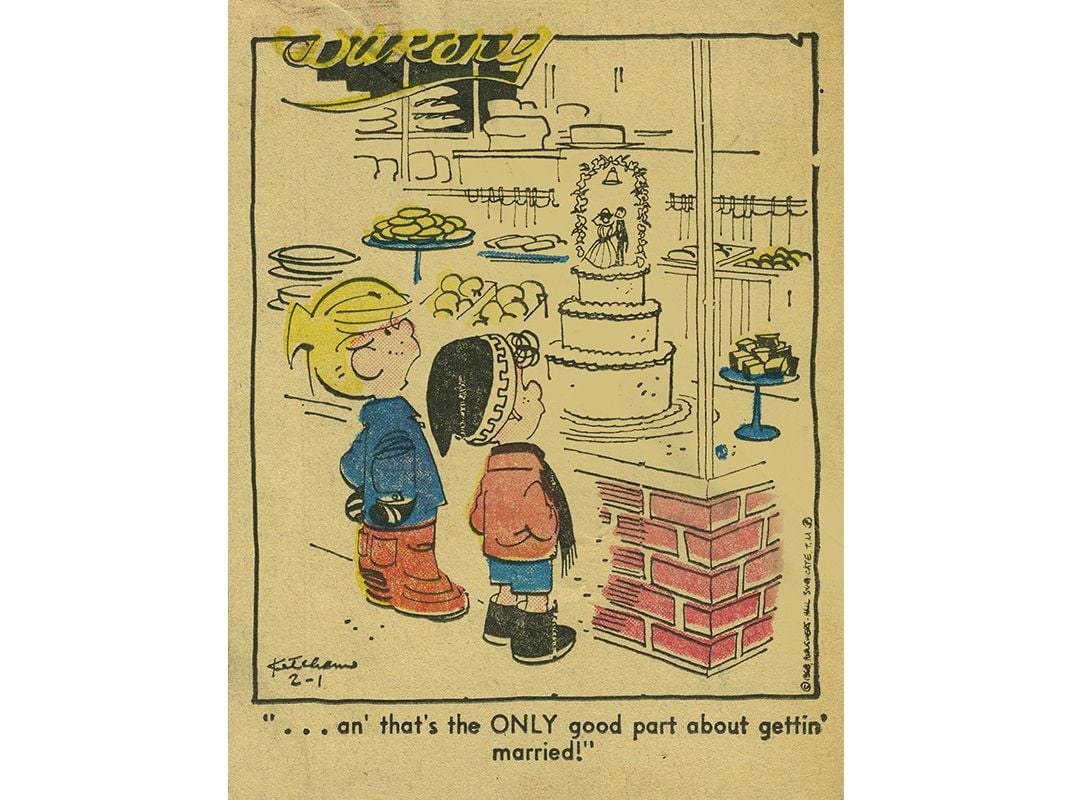

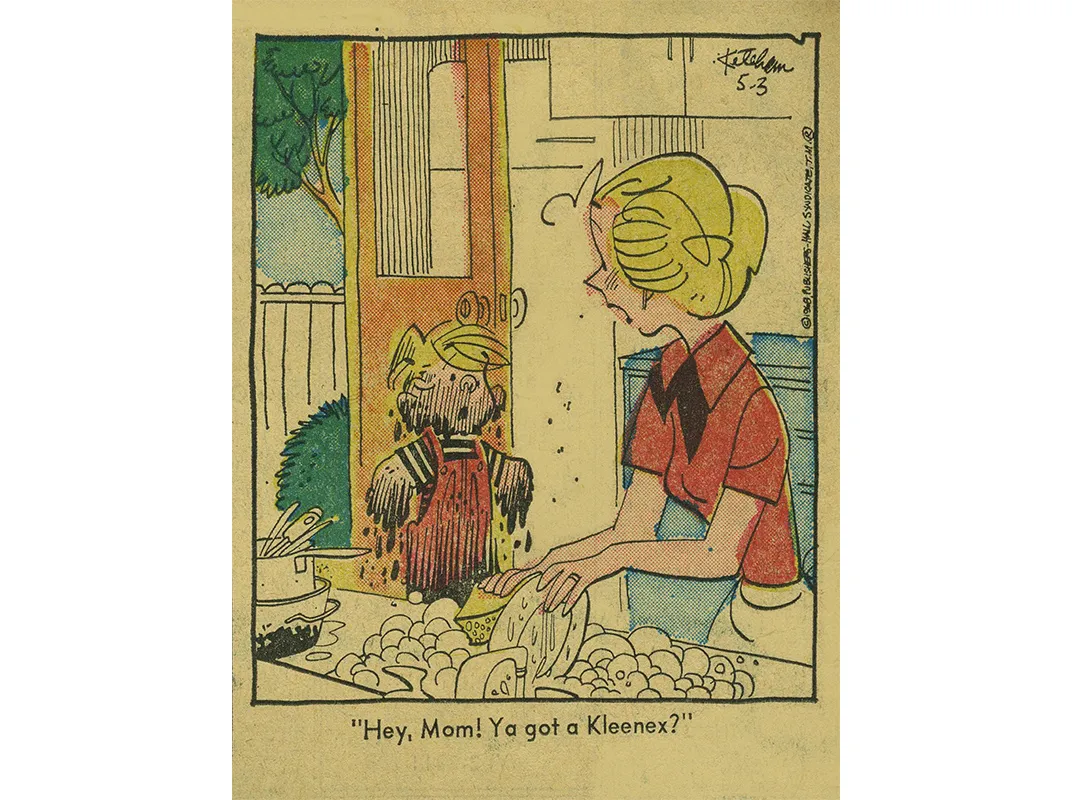

Mischief was the common concept: Both Dennises were rowdy boys, running amok, turning the grown-up world on its head. American Dennis was a little tearaway in dungarees, an adorable scamp pestering poor Mr. Wilson next door. He did and said the darnedest things; you couldn’t stay mad at American Dennis. British Dennis was much further along the mischief spectrum—a disturbed maverick of prepubescence, a bully, a nemesis, a persecutor of “softies” (in particular the unfortunately recurring Walter), a mean-minded vandal with whom the authorities were in a permanent and justified rage.

Physically, the two were day and night: American Dennis was blond and cowlicked, with a round face and the short, ham-like forearms of a “Peanuts” character. British Dennis was knobby-kneed and low-browed, gleefully scowling under an inkblot of high-speed hair. The red and black stripes of his jersey expressed the buzzing wave band of his criminality. He carried a peashooter, water pistol and catapult, and his exploits generally ended in corporal punishment. British Dennis had a canine accomplice, Gnasher, who would have eaten American Dennis’ sweet dog, Ruff, in two seconds flat, and he later had a disgusting pig, Rasher. If he’d had a dubiously raincoated older-man acquaintance called Flasher it wouldn’t have been much of a surprise.

What accounts for the moral gulf between Dennis and Dennis? Take a look at a 1933 poem called “My Parents Kept Me From Children Who Were Rough.” The poet, Stephen Spender, was upper-class and Oxford-educated, a friend of W.H. Auden’s. He was, essentially, Walter the Softy, and in that poem, he gave eloquent voice to his feelings about the Dennises of his childhood: “I feared more than tigers their muscles like iron / And their jerking hands and their knees tight on my arms.”

American Dennis radiated the irrepressible energy of a young republic. In contrast, British Dennis represented a form of transgression that didn’t even exist in the United States. He emerged during a time of class struggle and waning empire, when the U.K. establishment feared the oik, the yob, the ungovernable prole. In short, British Dennis was a proto-punk-rock-hooligan. For young British schoolchildren, he was, and still is, an object of riveting terror (and on the shadow side, of yearning): the rough boy with the iron muscles and tiger stripes.

Dennis the Menace: The Classic Comicbooks

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/09/a509c0d6-574b-4266-a434-f0a3178a357d/mar2016_i01_phenom_web_resize.jpg)