Design for a Water-Scarce Future

Design strategies for arid regions go back centuries, but in the face of climate change, drylands design is a whole new ballgame

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120419103007powellmap470.jpg)

This is a story about a group of designers in Los Angeles in the year 2012, who are developing design strategies for the year 2020, or 2050, or beyond. But even this future-focused, west coast plot line has an historical thread that ultimately leads back to the Smithsonian. So that’s where we’ll begin. It won’t seem like a design story at first, but it will become one.

113 years ago, an ancestor of the Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology was established by the US Congress in order to archive research related to the American Indians. The Bureau of Ethnology, as it was initially called, fell under the direction of John Wesley Powell, a scientifically-inclined polymath who had explored the American West extensively and who ran the archive like a living lab for studying U.S. land and society.

Among the many publications Powell produced during his tenure, the most oft-cited is his Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, which was meant to illuminate for federal government officials back east how inappropriate existing land divisions would be in the intensely dry western territory.

Ensuring that settlers would be able to farm the land they acquired, Powell recommended that parcels be defined according to the natural water drainage patterns, and that farmers form self-governing bodies to manage their watersheds. “If these lands are to be reserved for actual settlers, in small quantities, to provide homes for poor men, on the principle involved in the homestead laws, a general law should be enacted under which a number of persons would be able to organize and settle on irrigable districts, and establish their own rules and regulations for the use of the water and subdivision of the lands.”

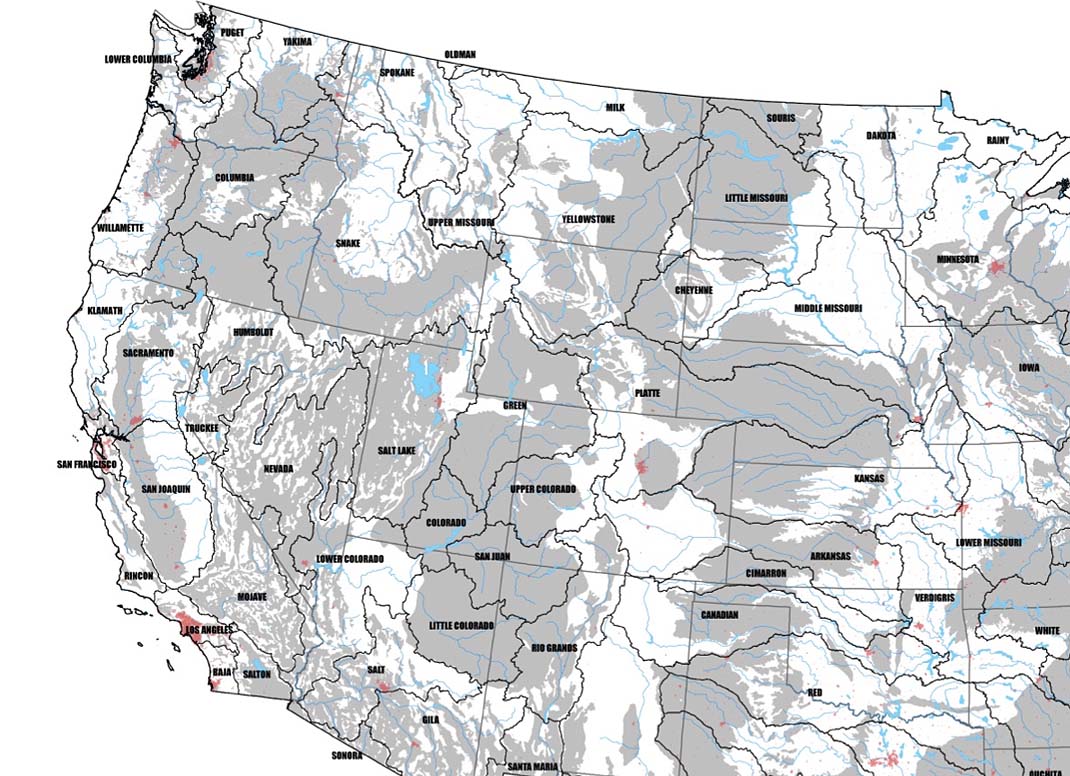

Powell recognized that the origin point of all the settlers’ potential water sources was snow. “The fountains from which the rivers flow are the snow fields of the highlands,” he wrote in his report. He also saw that this natural geological story would have to become an engineering story in order for western development to thrive. But the small-scale, cooperative approach he envisioned did not play out. Instead, over the next century, massive, energy-intensive infrastructure was built to transport water over vast distances. Family farms gave way to industrial agriculture, urban centers ballooned and became sprawl, public utilities gained power and influenced policy.

But for all the change, one important thing remains the same: We still get our water from snow. “30 million people in the U.S. West depend on snow,” says Hadley Arnold, co-director of the Arid Lands Institute (ALI) at Woodbury University, “We drink it, we grow our economies on it. We are a snowmelt-dependent society.” And that’s a problem, because global warming has altered the timing, volume and intensity of precipitation cycles. To quote from the exhibition materials for the ALI’s show, Drylands Design, at the Architecture + Design Museum in Los Angeles, “Current western water infrastructures deliver diminishing snowpack using energy sources that accelerate its disappearance.”

Arnold and her husband, Peter, founded the ALI—which bears echoes of John Wesley Powell’s legacy—with the goal of engaging design students and professionals, scientists, policymakers and the public around rethinking the built environment in the context of water scarcity. “The design of our infrastructure is obsolete,” Hadley says, “Not physically, in terms of rust or disrepair or the need for more, but conceptually obsolete. It is not designed to do the job that is needed to be done.”

Watershed Commonwealths, proposed by Robert Holmes and Laurel McSherry, 2012

And this is how we arrive at the increasingly common assertion that climate change is a design problem. More than a century after Powell challenged the government to design infrastructure and territorial boundaries in accordance with existing landscapes, the task for designers, architects, engineers and planners can no longer be only to follow some of Powell’s logic, but to find ways to undo much of the detrimental development that has occurred in the meantime. “We have to reverse all the engineering that has gone into building code and city infrastructure,” says Hadley. Drawing again on the ALI exhibition materials: “Captured rainwater, storm-water runoff, gray water and wastewater combined form the West’s largest undeveloped water supply. Opportunistically exploiting this supply requires, at every scale, an inversion of the usual order of things: flood as opportunity; surface as sponge; roof as cup; waste as sustenance; city as farm.”

To develop specific strategies around these goals, the ALI partnered with the California Architectural Foundation to organize a conference, a design competition and an exhibition. The image, above, comes from one of the winning teams from the competition, who took up Powell’s hydrologic commonwealth concept and adapted it to contemporary conditions. Over the next few weeks, we’ll be using the competition winners as well as the conference program and exhibition framework as launch pads to explore drylands design in terms of ecology, history, technology and economic markets. We’ll investigate the potential of an “Occupy Watershed” movement, and look at how designing highly visible water infrastructure, as opposed to hiding systems away from public view, could be one key to mitigating the water crisis. Stay tuned.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)