Designing Lives and Building Stories, Chris Ware’s Comic Book Epic

In Building Stories, cartoonist Chris Ware presents the banality of everyday life as a stunning comic epic

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121018054913building-stories_470.jpg)

I learned to read so I could figure out why Batman was throwing his costume into a fireplace on the cover of one of my dad’s old comic books. Ever since then I’ve been hooked on comics. And so I was incredibly excited to once again attend New York Comic Con this past weekend where, among the standard superhero fare and the novelty 25 cent comics, I picked up a breathtaking new, very un-Batman-like comic by one of my favorite creators, Chris Ware. Ostensibly, Building Stories is a comic book chronicling the lives of the occupants of a three-story apartment building. But it’s so much more than that. At once expansive and intimate, it is a masterpiece of storytelling, a fragmentary collection of sad and beautiful vignettes that began more than a decade ago as a series of comics serialized across several popular publications, including The New Yorker, The New York Times, and McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern.

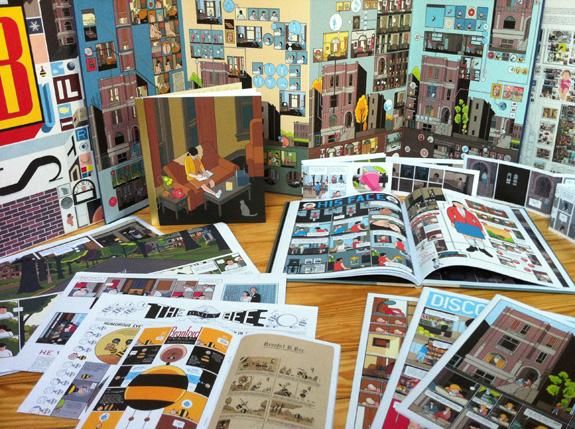

The first thing you’ll notice about the collected Building Stories is that it’s not a book. It’s a box. It looks more like a board game than anything else. However, inside this box, there isn’t a game board and there aren’t any pieces. Instead, there are the 14 distinct books that compose Building Stories – ranging in style from standard comics to flip books to newspapers to something that looks like a Little Golden Book. Importantly, there are no instructions on how to read them or where to begin. While these books do indeed trace the lives of a small group of people (and a honeybee), the linear narrative is irrelevant –we’re just catching glimpses of their lives– and reading through the encapsulated stories is reminiscent of flipping through a stranger’s old photo albums.

This format is critical to the experience of reading Building Stories. Everything has been carefully considered and painstakingly designed. Ware’s drawings are often diagrammatic and vaguely architectural; his page layouts read like complex maps of human experience. It’s worth noting here that Ware writes and draws everything by hand, giving the book, with its exacting precision, a sense of craftsmanship. And though it’s not always clear what path to follow, every single composition, whether clean or cluttered, has a profound effect on how the text is understood and how it resonates emotionally. Ironically, given the amount of detail in each drawing, Ware might best be described as an impressionist. A Monet painting doesn’t show us exactly what the water lilies looked like, but how it felt to see them.

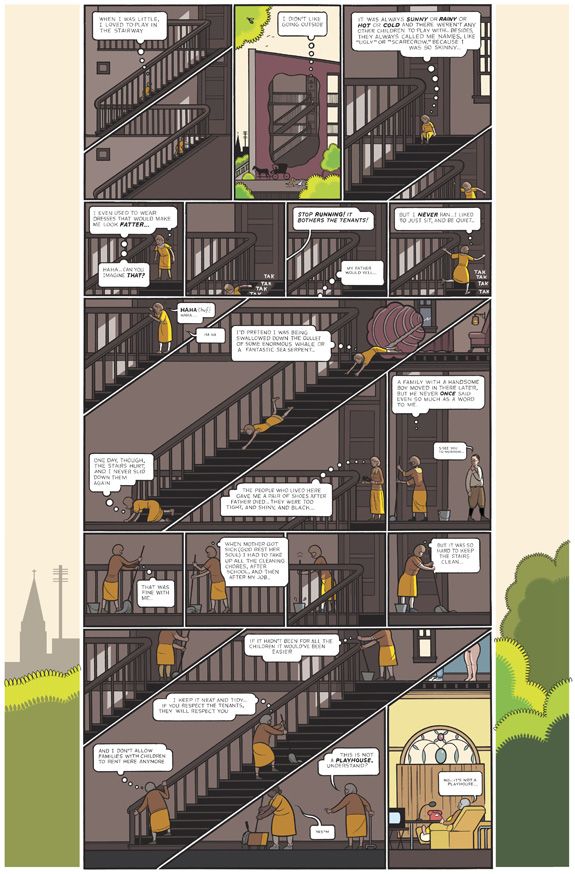

If there’s a central theme to Building Stories, it is the passing of time – and our futile struggle against it. The comic book is the perfect medium to explore this idea. After all, what is a comic but sequential, narrative art? Unlike a photograph, a comic panel does not typically show a single moment in time but is, rather, a visual representation of duration. That duration might be the time it takes Superman to punch out a giant robot, the seconds that pass while a failed artist chops a carrot, or the years it takes for a single seed to travel around the world. In every comic book, time passes within the panel. More noticeably though, time passes between the panels. This is where the art of storytelling comes in. There are no rules in comics that standardize the duration of a panel or a sequence of panels. In Building Stories, sometimes milliseconds pass between panels, sometimes entire seasons, and sometimes even centuries can expire with the turn of the page. The arrangement and size of images on each page affect the mood of the story and the pace at which it’s read. This manipulation of time and space and emotion is Ware’s greatest strength. He controls every aspect of the page, how the story is told, and how the story is read. Sometimes an entire page may be dedicated to a single glorious image of a suburban street; another page may be filled with dozens of tiny boxes in an attempt to capture every second of an event and make the reader feel the passing of time. The effect is sometimes reminiscent of an Eadweard Muybridge photo sequence – except instead of a running horse, the sequence depicts a young couple struggling through an awkward conversation at the end of a first date.

In another particularly striking page, an old women who has spent her entire life in the building ages decades as she descends its stairwell. In just that single page we learn so much about her life: her frustrations, her disappointments, her disposition, and above all, her connection to the house. It is this house which is truly at the center of the book. It is the one constant that remains relatively unscathed as time ravages its occupants. As the tenants pause from their own personal stories to wonder about a sound from the floor below, or ponder the mysterious architectural remnants left by their predecessors, the building ties their lives together for a fragile, fleeting moment. As characters grow and change and move on to other cities and other buildings, they wonder if they were happier in their old lives. Throughout it all, it becomes clear that our lives are impacted –and sometimes even changed– by the spaces we occupy.

With each panel, each page, and each book, Ware builds his stories. Stories of life, death, fear, love, loss, cheating. As the author himself writes, in his typical sardonic, slightly antiquated prose, “Whether you’re feeling alone by yourself or alone with someone else, this book is sure to sympathize with the rushing sense of life wasted, opportunities missed and creative dreams dashed which afflict the middle and upper-class literary public.” If it wasn’t clear by now, this is not a fun comic. But it is undeniably emotional. We’ve been telling stories through pictures as long as there have been stories to tell. Yet even with the relative success of graphic novels such as Persepolis and the explosion of comic book films over the last ten years, comics are still treated largely as a kid’s medium, as something less than literature or the fine arts. The combination of writing and art is its own challenging and complex art form. When executed well, a comic can be as powerful as Monet’s water lilies or as poignant as Catcher in the Rye. Building Stories should be held up as a shining example of what’s possible with the medium.

Oh, and if you’re curious about that Batman story, an insane psychiatrist hypnotized him to fear bats, forcing Batman temporarily to take on another identity. Pretty typical stuff, really.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)