Did Shakespeare Base His Masterpieces on Works by an Obscure Elizabethan Playwright?

The new book “North by Shakespeare” examines the link between the Bard of Avon and Sir Thomas North

:focal(377x266:378x267)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/42/9f422969-9ee2-4f26-b4e0-f1c927ebf13f/shakespeare.png)

“All’s well that ends well.”

It’s a memorable phrase—and the title of a play whose author is readily identifiable: William Shakespeare. But did the Bard of Avon originally write the Elizabethan comedy? And, more generally, did he conceive of and author many of the productions, ideas, themes and sayings attributed to him today?

New research suggests that a long-forgotten playwright might be the source of some of Shakespeare’s most memorable works. As journalist Michael Blanding argues in North by Shakespeare: A Rogue Scholar’s Quest for the Truth Behind the Bard’s Work, Sir Thomas North, who was born nearly 30 years before the Bard, may have penned early versions of All’s Well That Ends Well, Othello, Richard II, A Winter’s Tale, Henry VIII and several other plays later adapted by the better-known dramatist.

North by Shakespeare builds upon extensive research conducted over the course of 15 years by self-educated scholar Dennis McCarthy. Using modern plagiarism software and a sleuth’s keen eye, McCarthy has uncovered numerous examples of phrases written by the Bard that also appear in text attributed to North, a prolific writer, translator, soldier, diplomat and lawyer of his time.

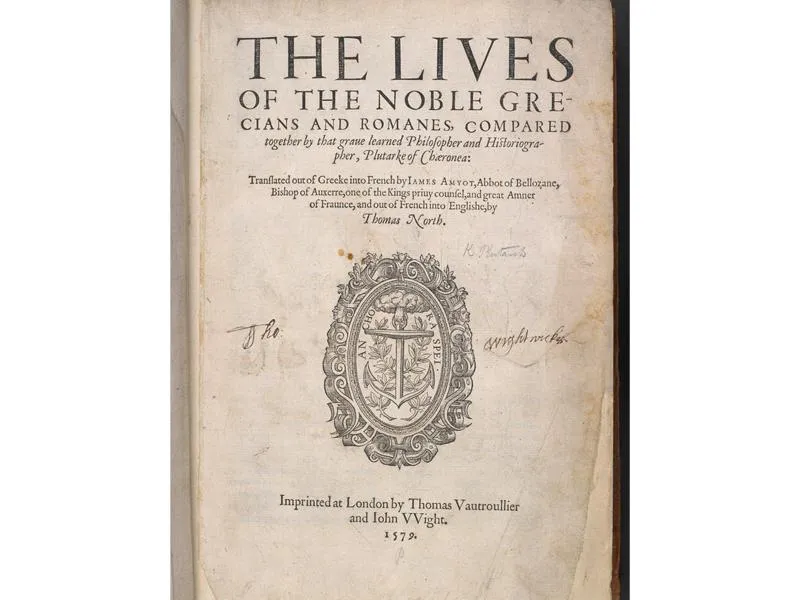

Born in 1535, North was the well-educated, well-traveled son of the 1st Baron North. Because of his translation of the Greek historian Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, North is widely recognized as the inspiration for numerous Shakespeare plays, including Antony and Cleopatra and Julius Caesar. North may have also written his own plays, some of which may have been produced by Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, in an attempt to woo Elizabeth I. Unfortunately, most of North’s works are lost to time—as are countless others from that time period.

North by Shakespeare: A Rogue Scholar's Quest for the Truth Behind the Bard's Work

A self-taught Shakespeare sleuth’s quest to prove his eye-opening theory about the source of the world’s most famous plays

In his investigation, Blanding follows two central narratives: McCarthy’s quest to learn more about Shakespeare’s sources and North’s 1555 trip to Rome, which would play prominently in the Bard’s writing of The Winter’s Tale and Henry VIII.

“Skepticism could be a word that you could apply to me in the beginning,” says Blanding. “I was vaguely aware of these theories that somebody else wrote Shakespeare’s plays, but never put much stock in them. When Dennis first told me about his ideas, I sort of rolled my eyes. When I looked at his research, though, I became impressed by the mass of evidence he had marshaled. It really seemed like there was something there.”

Scholars and historians have long agreed that Shakespeare borrowed ideas and adapted plays from contemporary sources and authors, as well as earlier writers like Plutarch and Roman dramatist Seneca. Drawing on others’ work to create one’s own was common in the Elizabethan era, with fellow playwrights Ben Jonson and Christopher Marlowe, among others, following suit.

Even for its time, however, McCarthy found that the degree to which Shakespeare used themes, titles and direct phrases from North’s writing is considerable.

Perhaps one of the most obvious examples of the connection between the two comes from Richard II. North’s translations of Dial of Princes and Plutarch’s Parallel Lives contain extended metaphors echoed in the Shakespeare history play.

In his works, North likens kingdoms to land with fertile soil: They “bringeth forth both wholesome / herbs and also noisome weeds.” To ensure the healthy plants’ survival, one must “cut / off the superfluous branches.”

Shakespeare penned similar lines for the gardener in Richard II, who tells a servant to “Go thou, and like an executioner, / Cut off the heads of too fast growing sprays, / That look too lofty in our commonwealth.” He then states his intention to “go root away / The noisome weeds which without profit suck / The soil’s fertility from wholesome flowers.”

Reflecting on the deposed king’s wasted potential, the gardener adds, “O, what pity is it” that he failed to lop off the “superfluous branches … [so] that bearing boughs may live.” North’s Dial, for its part, also uses the phrase “O, what pity is it.”

Another strong example is presented in an original excerpt from North’s Journal, which describes a gathering witnessed during his recent trip to Rome:

After them followed two, carrying each of them

a miter, and two officers

next them with silver rods in their hands.

Then the cardinals having a cross borne before them, and every cardinal his several pillar borne next before himself;

After them comes the Pope’s holiness…

The text’s sentence structure directly parallels the stage directions for a scene in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII:

Enter two vergers with short silver wands; next them, two Scribes, in the habit of doctors; after them, Canterbury alone … Next them, with some small distance follows a Gentleman bearing … a cardinal’s hat; then two priests, bearing each a silver cross; … then two gentlemen bearing two great silver pillars; after them, side by side, Cardinal Wolsey and Cardinal Campeius.

The two passages are so strikingly similar that both McCarthy and Blanding believe the only explanation is that Shakespeare used North’s journal as his source material. They argue that countless other examples—so many, in fact, that they cannot be ignored—show the similarities between the two playwrights.

“Scholars have already identified a number of source plays for Shakespeare,” Blanding says. “Most of them have been lost. They’ll say that Philemon and Philicea was the source play for Two Gentlemen of Verona, or Phoenecia was the source play for Much Ado About Nothing. The leap Dennis is taking is that they were all written by Thomas North. [Shakespeare is] not creating them out of thin air.”

Emma Smith, a prominent Shakespearean scholar at the University of Oxford in England, calls the theory that the Bard used North’s plays, most of which no longer exist, “interesting.” The author of the 2019 book This is Shakespeare, she doesn’t completely dismiss the idea, but finds it difficult to substantiate without solid proof.

“Shakespeare did copy word for word in some cases,” she says. “But the kinds of borrowing of words and phrases we see as parallels in this book have not until now been seen as hints at a more thorough rewriting of a lost text. If all these plays of North’s are lost, it’s impossible to prove.”

Another Shakespeare expert, June Schlueter of Lafayette College in Pennsylvania, was one of the first scholars to agree that McCarthy’s theory had merit. The pair collaborated on two related books: A Brief Discourse of Rebellion and Rebels by George North: A Newly Uncovered Manuscript Source for Shakespeare’s Plays and Thomas North's 1555 Travel Journal: From Italy to Shakespeare, which was published in January.

Though Schlueter acknowledges that most of North’s works are lost to time, she says enough references to them appear in other sources to substantiate their context.

“What if Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare, but someone else wrote him first?” she muses. “That’s exactly what we are arguing. The evidence is quite strong. Very strong, I think.”

Schlueter is quick to defend the Bard as a genius and incredibly intuitive playwright, deserving of the acclaim he rightly receives. But she thinks McCarthy has unlocked a passageway into a new understanding of Shakespeare’s inspiration.

“We are not anti-[Shakespeare],” she says. “We don’t believe that the Earl of Oxford, Francis Bacon or even Queen Elizabeth wrote Shakespeare’s plays. We believe he wrote them but … based them on preexisting plays by Thomas North.”

How Shakespeare got his hands on North’s plays is still unknown. The men most likely knew each other, though, and several documents reference a possible meeting between the two.

As the second son of a baron, North missed out on his family’s inheritance, which went entirely to the first son. According to Schlueter, the writer was impoverished by the end of his life and may have sold his plays to Shakespeare just to survive. Payments in North’s older brother’s records coincide with known dates of productions of Shakespeare plays with ties to the second son.

“I think Shakespeare was a brilliant man of the theater,” Schlueter says. “He knew how to take those plays by North and turn them into something that would be appealing to audiences in the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras. He updated those plays and made them his own. He’s entitled to have his name on them.”

McCarthy, for his part, argues that 15 years of exhaustive research have turned up solid evidence for the North connection. He first observed similarities between the playwrights while studying how Hamlet, which started out as a Scandinavian legend, made its way from Denmark to England. Now, he can cite examples ad infinitum of text written by Shakespeare with a distinct connection to North.

“Shakespeare used source plays,” he says. “Everyone agrees with that. It’s not something I discovered. There are early allusions to these plays long before Shakespeare could have written them. There is a reference to a Romeo and Juliet on stage in 1562, two years before Shakespeare was born.”

McCarthy adds, “While scholars have long known these plays existed, they had no idea who had written them. I believe I’ve solved that question, and the answer is Thomas North.”

One of the researchers’ most important clues comes from a private journal written by North in 1555. Detailing the writer’s tour of Rome the previous year, a 19th-century copy of the original was recently discovered by McCarthy and Schlueter in a library in California. In the diary, North describes statues by Renaissance artist Giulio Romano as “lifelike” and “extraordinary.” At the end of The Winter’s Tale, Shakespeare, who is not known to have traveled to Italy or studied sculptures from that period, includes similar references to the artwork and artist.

“[Scholars have] been trying to figure out how Shakespeare knew about the work of Giulio Romano, and there it is,” says McCarthy. “This has been a big Shakespeare mystery for many, many years.”

As can be expected, McCarthy’s theory has come under close scrutiny by many scholars. His revolutionary ideas, which upend a long-held belief of the Bard as a brilliant but singular playwright, have generally been met with cynicism and downright scorn.

“A lot of the time their reactions are comically hostile,” McCarthy says with a laugh. “That’s fine, but I think if they just take a breath and actually look at my arguments, they might get what I’m saying. They don’t even have a candidate for some of these early plays that influenced Shakespeare. Why would you be out-of-your-mind enraged at this idea that this person had a name and his name was Thomas North?”

The lack of irrefutable evidence means the debate will likely continue in academic circles for years to come. That could change if a long-lost North play should happen to turn up—a scenario McCarthy likens to a “treasury of everlasting joy.”

In the meantime, Smith remains unconvinced that North was the author of the plays that influenced Shakespeare. Short of a “smoking gun,” she and many other scholars will err on the side of caution.

“Shakespeare studies are full of people who are very, very clear about the shape of the things that we have lost,” she says. “The point is, we really don’t know.”

Editor's Note, April 6, 2021: This article previously stated that North's work was widely recognized as a source of inspiration for Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus. In fact, Antony and Cleopatra is more commonly associated with North. The piece has also been updated to more accurately characterize North's Dial of Princes.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)