I first heard about Val Shively—a legendary figure among serious record collectors—from a friend of mine in Philadelphia named Aaron Levinson. He’s a Grammy-winning music producer, composer, DJ and rare vinyl collector who has been buying records from Shively for 40 years.

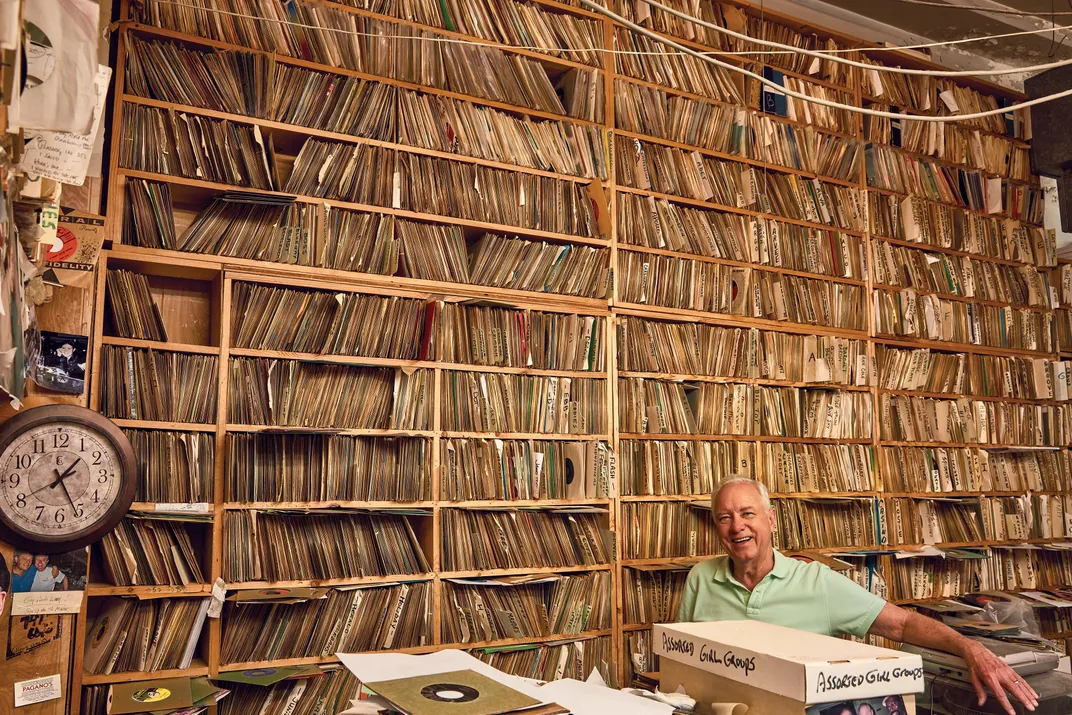

“He has a store called R&B Records in this sketchy neighborhood out past West Philly,” Levinson told me. “The building is listing like the Tower of Pisa because he’s got five million records in there. It’s likely the biggest record store in the world and collectors fly in from the U.K., Germany, Japan and wherever else, in order to buy from Val. But if they say something wrong, or he doesn’t like their attitude, he explodes in an unbelievable rage and throws them out of the store.”

Levinson continued, “He’s a born-again Christian who curses like a mobster. He’s a white guy who went nuts for Black music when he was young and never recovered. He’s the authoritative collector of doo-wop records on the planet and one of the greatest record collectors of all time, even though his genre is narrow.”

I asked Levinson about the possibility of interviewing Shively and writing about him. “I’ll see what I can do,” Levinson said. “He’ll probably test you first, or make you run some kind of gauntlet, but at this stage of his life, he might appreciate the validation.”

Two days later, Levinson gave me Shively’s cellphone number and a word of advice.

Don’t use the term “doo-wop,” he said. “Val and his dwindling band of fanatics call them ‘group harmony records,’ or ‘group records,’” he explained.

I called the number. Shively made some small talk and then launched into a monologue, talking fast with an abrasive Philly accent (actually a Delaware County, Pennsylvania, accent, I found out later). He was describing a recent period of psychological malaise. “I’m a Christian, okay, and I was praying, but nothing was happening,” he said. “I couldn’t see the point of any of it—the music, my life, my record collection, the store—and I had no energy.” He’s 77 years old. “I thought maybe that’s the problem.”

But in the last few days, he said, the empty feeling had lifted, his energy had returned, and he was feeling like himself again. I asked him what he thought accounted for the change. “To be honest, I have no clue,” he said. Then he asked, “What do you know about my type of music, the group stuff?”

“Very little,” I said. “I know more about soul and funk.” I told him I was looking for a vinyl copy of “No Man is an Island” by the Van Dykes, a fairly obscure Texas soul group from the 1960s. “Oh, that’s good you know them!” he said. “They sound like four guys, but there’s only three of them. Normally three guys sound like whale s--- sinking to the bottom of the ocean.”

Then he summarized the Army career of the Van Dykes’ falsetto lead vocalist, Rondalis Tandy, and how the group was formed, who their influences were, the different record labels they were on, their best songs, and how and when they broke up. That segued into a series of stories about accidental improvisations in recording studios that led to big hits, the influence of mobsters in the music business, and singers who were in prison for murder while their hit songs climbed the charts. This amazingly well-informed soliloquy went on for 25 minutes. Then he said, “Okay, get over here and I’ll do whatever you want. What’s your address? I’m sending you a package.”

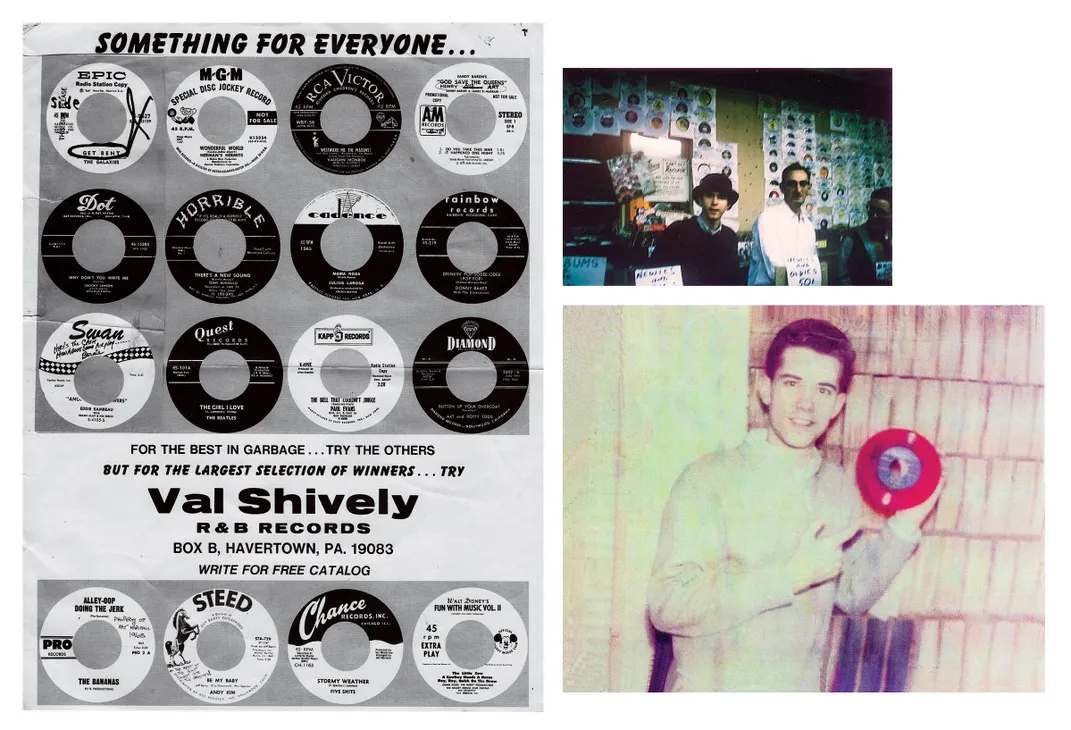

The package contained his religious testimony photocopied on a sheet of yellow paper, and five home-burned CDs featuring 149 rare African American doo-wop songs, mostly recorded between 1956 and 1959. A hand-scrawled letter stressed the importance of listening to the CDs in order. On the CD cases were blurry photocopied photographs of Shively at various stages in his career—teenage Val holding up a 45 single, mustachioed Val in the 1970s wearing a cowboy shirt, late-middle-aged Val in a turtleneck sweater. The wall of records behind him remained almost the same in each image.

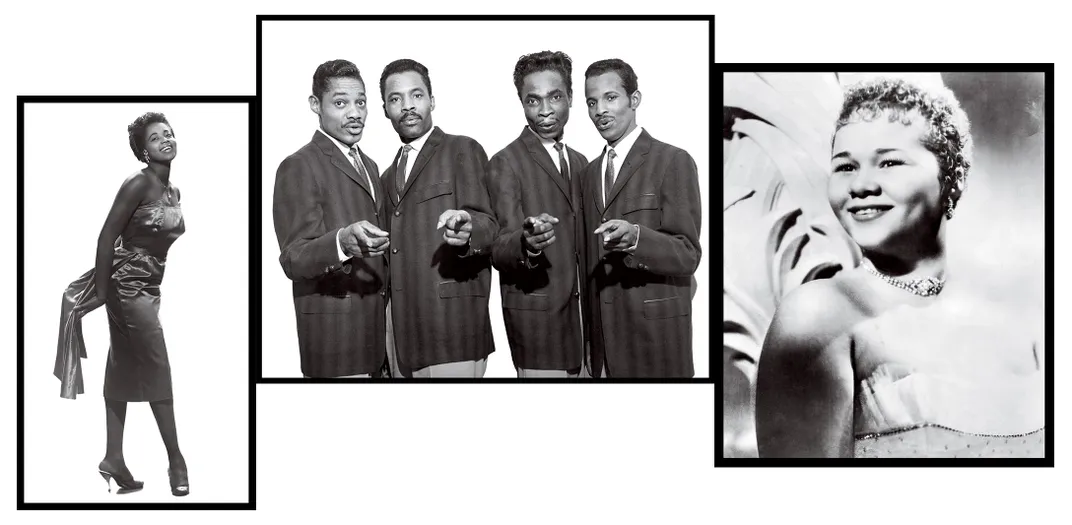

I listened to the CDs on the plane to Philadelphia, cocooned in my headphones, transported back to an era when cars had tail fins and young men in African American neighborhoods sang harmonies on street corners and formed groups such as the Quails, the Larks, the Feathers, the Opals, the Paragons, the Spaniels. I was a newcomer to this music and at first it sounded too stylized, sentimental and formulaic for my taste. Then the form of the music started to fade away and my ears opened up to the amazing lead vocal performances, the precision of the accompanying ooh-wahs and wop-wops, and the yearning, aching emotions evoked by the songs.

“Street corner opera,” is how Levinson describes this music: “The cult is around lead singers with crazy upper registers, plus the lushness and intricacy of the harmony singers. That’s what Val fell in love with and he never really moved on. He just tunneled deeper and deeper into it.”

* * *

From the center city of Philadelphia, Levinson and I took the subway out to 69th Street and emerged into the gritty, multiethnic streets of Upper Darby. We ate lunch in a Latin diner while Shively finished up his church services and then we walked over to his store. Actually we walked right past his store, realized our mistake, and turned back again. R&B Records has no sign or display windows, just a metal-framed door in the blank wall of a three-story building with a noticeable lean.

On the door was a “Do Not Enter” sign, with “Unless You Know What You Want!” printed across it in tiny letters. Another sign said, “New Rules. 5 Minutes and You’re Gone.” I was puzzled, so Levinson explained: “Val doesn’t allow browsing. Most of his business is mail-order, and if you come here as a customer, you need to have a list of what you want. And if you haggle over prices, or complain that he doesn’t have something, or act just a little bit snotty, your ass is going out the door.”

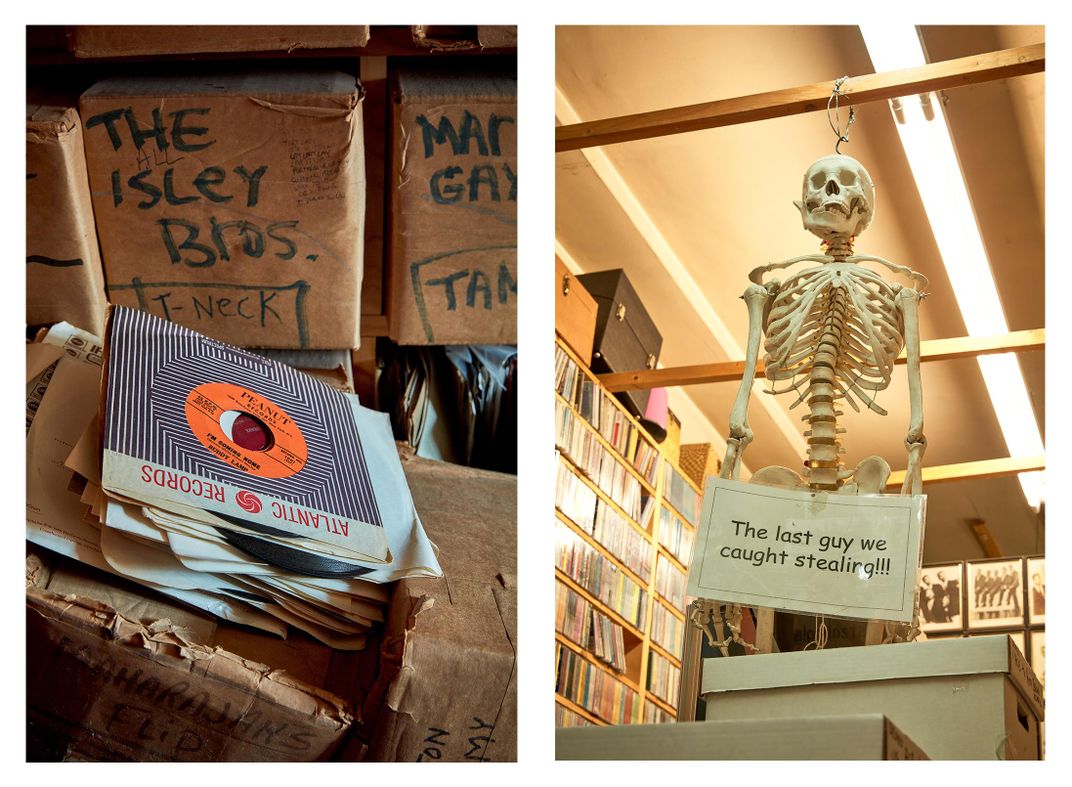

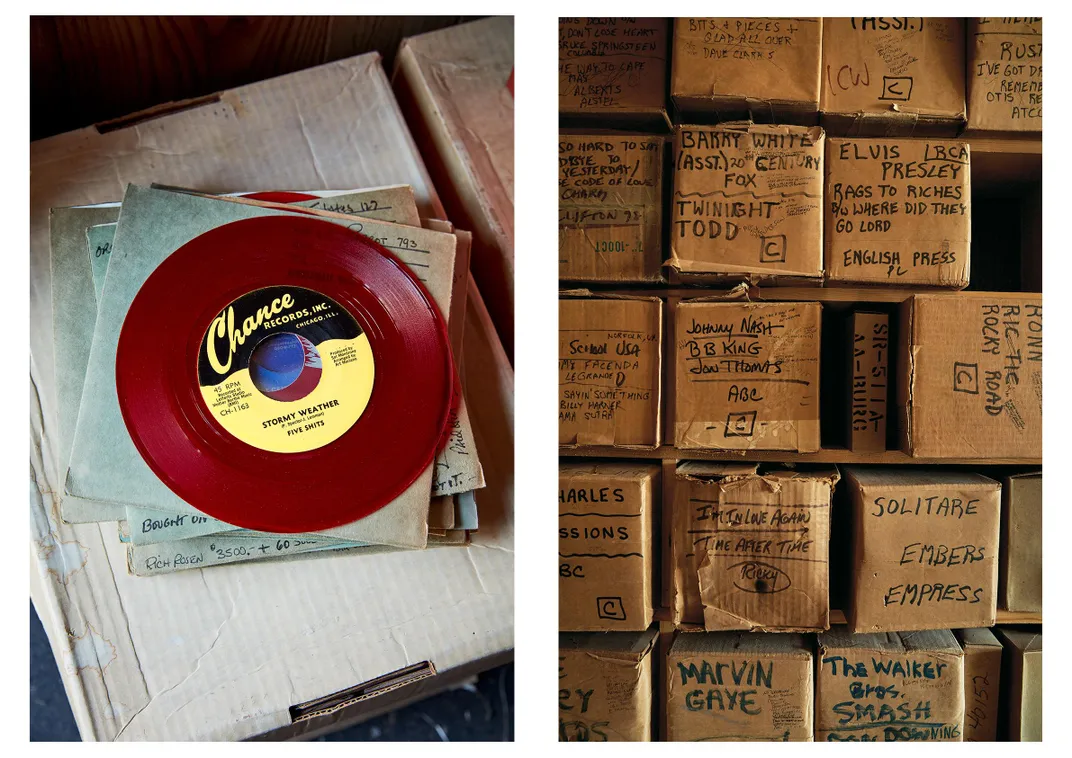

Stepping inside, I was confronted by a scene of overwhelming chaos and claustrophobic madness. Vinyl records were stacked on shelves to the high ceiling, with insanely narrow aisles between the towering stacks, and debris and garbage everywhere. The store hadn’t been cleaned in decades. Cats prowled around. A plastic skeleton hung from the ceiling with a sign on its midriff: “The last guy we caught stealing!!!” Another sign read, “Trespassers will be shot. Survivors will be prosecuted.”

And there in a small island of space, sitting at a scarred old desk heaped with Rolodexes, vinyl 45s, crumpled trash and random novelty items, was the white-haired emperor of this extraordinary domain. When he said, “Fat people can’t come in here,” he was not stating a policy. He was describing a physical reality. Levinson and I were of average girth, but the only way we could fit through the aisle to Shively’s desk was to turn sideways and shuffle.

He greeted us with an exuberant burst of profanity. He threw his arms out. “Look at this!” he said. “Complete insanity!” Of the five million vinyl records that he estimated were in the building—on two stories above us in equally overcrowded conditions and in the truly hellish chaos of the basement—more than four million were seven-inch 45 rpm singles. He bought them in bulk from bankrupt jukebox companies, radio stations, record companies, record stores, pressing plants, distributors and individual collectors. “Nothing in here is computerized,” he said. “I hate computers and we don’t need them. Chuck knows where everything is.”

He called out for his assistant, Chuck Dabagian. From a dimly lit slot canyon in the far stacks, shuffling smoothly sideways, there emerged a calm, introverted man who started working for Val as a teenager in 1972. Like his boss, Dabagian commands a mind-boggling knowledge of American music and African American music in particular. “Everything in the store is arranged by record label and then it’s alphabetized,” Dabagian said. “Val and I know all the labels—which label the original pressing was on, and which label the other pressings were on.”

“Labels are a sickness,” said Shively. “When I started collecting, I didn’t give a s--- about labels. Then I had to have everything on the original label, even if it took all the money I had. You start out loving the music and then it takes over your life. But, hey, it’s been a great life and I wouldn’t trade it for all the money in the world.”

* * *

In 1956, at the age of 12, Val Shively heard Don’t Be Cruel by Elvis Presley for the first time. He was never the same again. “That record destroyed me,” he said. “We had no money, so our neighbors bought me a record player. It hooked into the back of the television and played through the speakers. I would climb behind the TV and listen to that record for hours and hours. I drove my parents nuts.”

He was already a collector of stamps and coins. Now he focused on records and became obsessed with music. For his 13th birthday he was given a transistor radio. “I found a big thick book, The Life of Samuel Johnson, cut the middle out of it, and put the radio in there,” he said. “I punched holes in the cover so I could listen to the radio all day at school, and under my pillow at night. I had a paper route, and whenever I had money, it was records, records, records.” By age 15, his collection numbered in the thousands.

One day in 1960 Shively turned the dial of his transistor all the way over to the right-hand side and landed on a Black radio station for the first time. “It blew my mind, hearing Etta James, Baby Washington, “Valerie” by Jackie & the Starlites,” he said. “I like a lot of white music, I love old country, but for me, Black music has more force, more originality and more longevity. And once I got into the Black harmony groups, that was it. Nothing else ever sounded so good to me.”

He had no girlfriend or social life. He hated school. All of his free time was spent in pursuit of group harmony 45s, and like any true collector he was inexorably drawn to the rare and elusive. “Collecting is all about the hunt,” he said. “You move heaven and earth and pay whatever it takes to get that one record. But once you have it, it’s just another record and you hardly ever play it. Some people call it an addiction. I call it a disease.”

Hunting for these doo-wop gems, most of which were recorded by teenage nobodies and sold very few copies, Shively searched through record stores all over Philadelphia. On weekends he caught the bus to New York City and made his way to Times Square Records (known familiarly as “Slim’s”), a scruffy little store in Manhattan, presided over by Irving “Slim” Rose. That was the doo-wop mecca in the early 1960s, and a hotbed for the scamming and hustling that goes on among collectors. “People tricking each other, bluffing, double-crossing, trying to pass off bootlegs—it’s all part of the game,” said Shively. “Everyone is trying to get the rarest, most valuable records for the least amount of money.”

To finance his collecting, Shively started selling records. “In ’62, I had a record player in my car and I’d make the rounds on payday,” he said. “I’d say to people, ‘Get in the car and listen to this.’ I sold a lot of records that way, but this has never been about money. This has always been about me having the greatest collection of the music I love, as a way to be somebody.”

These ambitions were hard on Val’s mother, who wanted him to have a professional career. To keep her happy, and because he was good with numbers, he trained as an accountant. Then, to his mother’s horror he got a job doing the books for a record distributor—“Not the records again!” she lamented—and also delivering records to stores in North Philadelphia. Sometimes he bought so many records on his rounds that it canceled out his paycheck.

In 1966, he started sending out a small catalog to fellow group harmony collectors, offering records for sale and listing the rarities he wanted to buy. That was the beginning of a mail-order business that continues today. In 1972, Shively quit his job with the distributor and started selling mail-order records out of his house. It was financially sustainable, but the isolation got to him. “I’m famous for throwing people out of my store, but I love people and I need to be around them,” he said. That’s why, in November 1972, he opened the original R&B Records, a few blocks away from its current location.

He moved into his current space in 1990—and then gradually lost control of it. “I like a scruffy aesthetic, like Slim’s used to be, but I never intended for the store to get this bad. I buy like a hog, that’s the real problem. In ’91, I bought a million 45s from a jukebox company that went bust in New Orleans. They were heavy on soul and that’s my best-selling stuff now. Soul, funk, gospel. That’s what people come from Europe and Japan to buy.”

I asked him when he last threw someone out of the store. “Oh no, I don’t do that anymore,” he said. “That’s not true,” said Dabagian. “He still uses the eject button. What about that guy the other week?” Shively’s eyes bulged. His face flushed with rage at the thought of that guy. “Don’t come in here and tell me how to run my business!”

* * *

Only one customer entered the store the afternoon I was there. He was a 74-year-old named William Carter, who started buying records here 30 years ago. “I’m a 45 man,” he told me. “I want to play what I want to play. On a CD or an album, you have to play what they want you to listen to.” He gave his list to Shively, who handed it to Dabagian, who shuffled off on a goat path into the stacks.

As I eavesdropped on his conversation with Carter, Shively revealed another side of himself. This famously irascible crank could also be warm, kind, generous and empathetic—a solid friend. Before he left the store with his records, Carter said, “Val is a good man with a good heart. Don’t let anybody tell you different.”

It was now late in the afternoon and Dabagian was dispatched into the stacks for one last errand. When he reappeared, he was holding a vinyl 45 of “No Man is an Island” by the Van Dykes. Then Shively closed up the store and drove Levinson and me to his home to meet his wife, Patty—they met 50 years ago on a blind date at a bowling alley—and show us his record collection.

Two stories high on a quiet leafy street, in a solidly middle-class neighborhood, the house could have belonged to a dentist or a high school principal. It was attractively furnished and, compared with R&B Records, shockingly clean and uncluttered. “I’m a claustrophobic neat-freak,” Patty said. “I hate going into Val’s store. I won’t do it anymore.”

Now retired from a managerial job at a life insurance company, Patty had a slightly long-suffering air when it came to Shively’s obsession. She had once organized a “Wives Against Collecting” club, and she became furious some years ago when her husband gave the wrong answer to the following question: “If the house was burning down, which would you save first, me or the records?”

Shively said, “I’ve learned the right answer to that question now, I just needed a little help.”

Patty had no interest in Shively’s music and at their wedding 20 years ago she dismissed the vocal harmony group that he had hired. “It sounded like a funeral dirge,” she said. “Me and my friends wanted to dance.”

At the top of the stairs, Shively unlocked a door and we gazed at a wall of approximately 11,000 group harmony 45s—all first pressings, all the finest copies known to exist, nearly all in mint or close to mint condition. They were neatly shelved in brown covers and arranged carefully by label. “This is what I’m all about,” said Shively. “This is what I’ve been doing my whole life.”

One of his most prized possessions, for which he paid $10,000, is “Can’t Help Loving That Girl of Mine” by the Hide-A-Ways on Ronni Records. “It’s probably the most desirable record in the whole shooting match,” he said. “Not only is it a rare record. It’s a great record and they never made a dime off it.” Then he pulled out “Rosemarie” by the 5 Chimes on Betta, a record so rare it was thought to exist only on bootlegs. “I’m not happy to say that I paid $16,000 for this one,” he said. “That’s the most I’ve ever spent on a record.”

For every single record in the collection, Shively had stories, information, minutiae. He told us about the performers and their relatives and what happened to them later in life. He knew where the songs came from, and the backing musicians. There were also 11,000 stories about hunting down and gaining possession of the records—in nerve-racking blind auctions conducted by telephone with other collectors around the country, in miracle dumpster finds behind defunct radio stations, in hard-boiled negotiations with his peers.

Shively’s personal collection, the crowning achievement of his life, was also his biggest problem. “I hate to sell it because it means so much to me, but I don’t want to dump the problem on Patty when I die,” he said. “She doesn’t need to sell off all these records, which are worth millions of dollars, or deal with the people who want to buy them. ”

He stared at the wall of records. “I don’t know what I’m going to do,” he said. “I can’t be alive and not have this.”

* * *

Shively’s nearest equivalent in the rare record trade is perhaps John Tefteller, a mail-order dealer in Oregon recognized as having the best collection of blues 78s and 45s. “As soon as I knew anything about collecting, I knew about Val and over the years we became friends,” he told me.

Tefteller recently came up with the suggestion that perhaps the Library of Congress could purchase Shively’s collection.

“That’s where it belongs,” says Tefteller. “It is the single best collection of R&B vocal harmony groups on the planet and no other collections come close to it. If it were broken up and sold to other collectors, you could never again recreate the collection.”

Tefteller added: “Nothing will ever replace Val himself. No one else knows even close to what he knows about this music. Someone needs to sit down with Val and go through it all, record by record, and get all of Val’s stories. Otherwise all that knowledge will die with him.”

Matt Barton, the curator of recorded sound at the Library of Congress, had expressed a strong interest in seeing the collection, and Shively was looking forward to cataloging and pricing the records in preparation for Barton’s possible visit later this year. “I’ve never had children because my records are my children,” Shively told me on the phone. “It will be great to sit down and get to know them all again.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/15/d91578cf-2f9f-4846-a9da-260e83813919/mobile_opener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2d/92/2d92063e-6013-4413-bf00-b78a4c26a057/opener.jpg)