Doo Wop by the Sea

Architects and preservationists have turned a strip of New Jersey shore into a monument to mid-century architecture. Can they keep the bulldozers at bay?

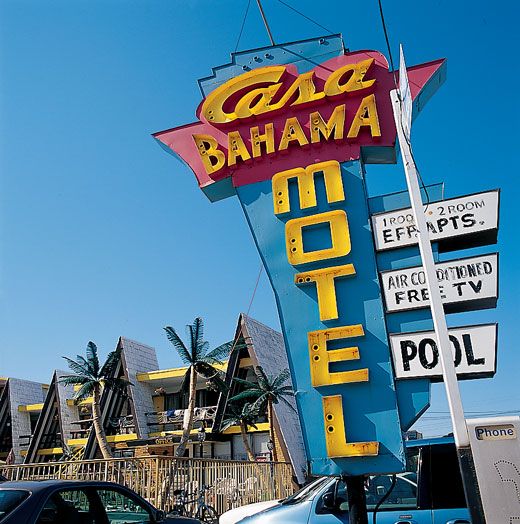

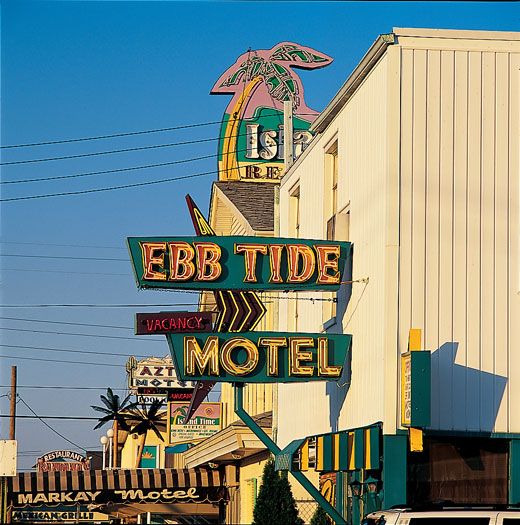

“We call this the Pupu Platter style of architecture,” says Joan Husband, pointing to the Waikiki motel on Ocean Avenue in Wildwood Crest, New Jersey. As our sight-seeing trolley rolls along on a steamy summer evening, local preservationist Husband, 56, keeps up a running patter at the microphone: “It has the thatched roof over the canopy, the Diamond Head mural on the side and lava rocks built into the walls.” We swivel in our seats for a better view. The motel-packed strip before us suggests an exotic, if confused, paradise far, far from New Jersey: we pass the jutting Polynesian roofline of the Tahiti; the angled glass walls and levitating ramp of the Caribbean; and the neon sputnik and stars, sparkling in the twilight, of the Satellite motel. Oddly perfect palm trees fringe motel swimming pools; Husband helpfully identifies the species—Palmus plasticus wildwoodii. “It grows right out of concrete.”

The people who built the nearly 300 motels along this five-mile section of the JerseyShore in the 1950s and ’60s could not have foreseen that their properties would one day warrant architectural tours, however tongue-in-cheek the spiel. The garish establishments crowd three shore towns known as the Wildwoods (North Wildwood, Wildwood proper and Wildwood Crest), occupying a stretch of barrier beach south of Atlantic City and just north of the restored Victorian resort town, Cape May. Most of the buildings sprang up when the Wildwoods were in their glory days as a beach resort. With so much competition, the motels here had to scream for attention—it was survival of the loudest.

Today, the buildings constitute an unplanned time capsule of mid-century American resort architecture, worthy, say architects and historians, of study and preservation. The towns’ gaudy motel districts, in fact, are considered a shoo-in for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places in the next year or two. To Philadelphia architectural historian George Thomas, 58, the Wildwoods’ motels are “a collision between the techy modern and tacky Art Deco. This isn’t the awful high architecture that has bored us to tears and given us places that no one wants to be,” he says. “This is the energy of American culture at its most useful and exuberant.” Unfortunately, the brash spirit of the Wildwoods’ venerable mom-and-pop motels is now threatened by the onrush of 21st-century development. With the value of ocean-view land soaring, vintage motels are starting to disappear as their owners sell to condo builders. “An awful lot of demolitions have taken place recently,” says local businessman Jack Morey, 42. “If the big guys eat the little guys, then the Wildwoods lose their character and might as well be anyplace.”

Well, not anyplace. In the summer, people queue up for monster-truck rides on the beach, and the switchboard operator at city hall works in bare feet and a T-shirt. The communities’ true Main Street is a broad wooden boardwalk—about two miles of amusement piers, high-decibel music and fried-dough stands. In July and August, it’s jammed with sunburned people, many wearing tattoos and talking loudly. The eye-catching motels, with their beckoning neon signs, are a stylistic extension of the boardwalk. There are cantilevered roofs and thrusting pylons, and colors like aqua and shocking pink. “Whoever has the concession for turquoise motel curtains in the Wildwoods is really making money,” says Husband, a retired nurse who worked in a boardwalk gift shop as a teenager. Unlike drab way-station motels on the outskirts of cities, these places were built to be destinations worth spending a vacation in.

In 1956, J. B. Jackson, editor of Landscape magazine, defended this style of over-the-top design, then under attack by city-beautification types. In “all those flamboyant entrances and deliberately bizarre decorative effects, those cheerfully self-assertive masses of color and light and movement that clash so roughly with the old and traditional,” Jackson wrote, he discerned not a roadside blight “but a kind of folk art in mid-20th-century garb.”

Today, this folk art is more apt to charm than shock. Cruising down Ocean Avenue at night, I’m struck by how oddly harmonious the motels are. The multicolored neon signs pass by like so many colored gems, uninterrupted by the blinding white fluorescent tubing typical of gas stations and chain stores in 2003. “When it’s all lit up at night,” says waiter Chris Sce, 19, as he clears dishes at the Admiral’s Quarters Restaurant, “you feel like you’re on vacation, even if you’re working.” At the Hi-Lili Motel a few blocks away, Carmelo and Beverly Melilli, both 54, say they’ve been coming to the Wildwoods for 30 years. They love the lights, the colors. “It’s like time stood still,” Carmelo says. “Everything’s like it was 30 years ago. It’s perfect.”

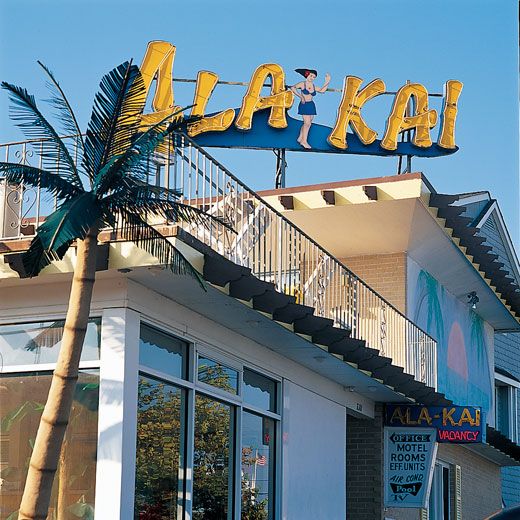

That pleasant time-warp feeling comes in part from the motels’ names, which summon up popular American fixations of the ’50s and ’60s. The Hi-Lili, for example, is named after the hit song “Hi-Lili, Hi-Lo” from the 1953 film Lili. Others evoke classic movies (the Brigadoon, the Camelot, the Showboat) and popular cars (the Thunderbird, the Bel Air). Hawaii’s 1959 statehood inspired the motel builders who put up the Ala Moana, the Aloha and the Ala Kai.

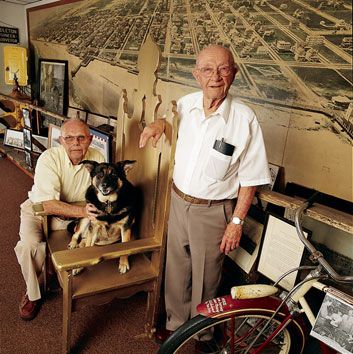

Local historian Bob Bright, Sr., remembers the Wildwoods in the days before neon. Still enthusiastic at 93, Bright holds court at a little historical museum on Pacific Avenue in Wildwood. When he was a boy, he says, the towns accommodated its visitors in large hotels and rooming houses. “They were made of wood from our own trees,” he says. “Wildwood was named because the whole town was nothing but trees!” He hands me a photo album of rambling three and four-story Victorian hotels. “Those old buildings were beautiful with their spires and towers, just like Cape May.”

Postwar affluence and mobility brought change to the Wildwoods, as it did everywhere. In summer, working-class Philadelphians and New Jerseyites with growing incomes hopped into their cars and cruised down the brand-new Garden State Parkway to the Jersey Shore. In the Wildwoods, days at the beach and on the boardwalk were followed by nights at the music clubs that crowded downtown Wildwood, known in the ’50s as Little Las Vegas. Motels offered vacationers advantages that hotels couldn’t match: you could park the new family car right outside your room and you didn’t have to shush the kids.

In the Wildwoods, the beach’s steady eastward migration—ocean currents have helped add an average of about 15 feet of sand per year—aided the motel boom. Surf Avenue, for example, which is now three blocks from the ocean, was indeed surf early in the 20th century. By the ’50s, the old wooden buildings were landlocked, and the motel developers could build on virgin oceanfront property. This accounts for the pleasing architectural rhythm of the Wildwoods’ low-rise motel districts, great swaths of which are uninterrupted by out-of-scale anachronisms.

Many builders looked south for style. “My dad, Will Morey, built several of the early motels here, like the Fantasy and the Satellite,” says Morey, whose family operates four Wildwood amusement piers. “He’d take ideas from Florida and other places and ‘Wildwoodize’ them, that’s the term he used.” If angled windows and wall cutouts looked classy on a Miami Beach hotel, he’d scale them down and try them on a Wildwoods motel. Beneath their surface pizzazz, of course, the motels were cinder block Ls and Is overlooking asphalt parking lots. Just as Detroit used tail fins to make overweight cars look fast, builders like Will Morey used angles and asymmetry to make motels look stylish and, above all, modern.

By the ’70s and ’80s, however, the motels began to show their age. They continued to draw customers, but there were fewer families and more boisterous young singles. “Bars were open until 5 a.m.,” says neon sign maker Fedele Musso, 51, who in the ’70s owned an arcade and a food stand on the boardwalk. “All these beer joints were selling seven beers for a dollar, which didn’t help much.” Seedy eyesores marred the motel strip. But because the local economy was in the doldrums, there was little incentive to knock down motels and put up something bigger.

Moreover, the Wildwoods, unlike warm-weather resorts Miami and Las Vegas, suffer a short tourist season, which limits profits and, in turn, the improvements motel owners can afford. “In the off-season, the parking meters are removed and the traffic signals change to flashing yellow,” says Philadelphia architect Richard Stokes. “They even take the fronds off the palm trees.” For preservationists, the short season is a blessing: it has deterred hotel chains from swooping in and putting up high-rises.

The Wildwoods’ discovery as an improbable design mecca began in 1997. That year, the late Steven Izenour, a champion of vernacular architecture who was part of the Philadelphia architectural firm Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, helped lead design workshops he called “Learning from the Wildwoods” with architectural students from the University of Pennsylvania, Yale and Kent State. “It can be a counter-Disney,” Izenour told a New York Times reporter in 1998, referring to the Wildwoods’ cluster of motel kitsch. “The more you have Disney, the more you need Wildwood.”

That same year, a handful of local motel-ophiles banded together to form the Doo Wop Preservation League, aimed at boosting appreciation for the resort’s architectural heritage. The name Doo Wop, known as Googie or Populuxe in Los Angeles, South Florida and other pockets of flamboyant mid-century architecture, alludes to the Wildwoods’ heyday as an early rock ’n’ roll venue. (It was Wildwood’s own Starlight Ballroom that hosted the first nationwide broadcast of “American Bandstand” in 1957.) Doo Wop Preservation League volunteers lead the trolley tours, and charter member Musso oversees the group’s funky warehouse-cum-museum.

They are also in the rescue business. The greatest save to date is the Surfside Restaurant, a circular, steel-structured 1963 landmark in Wildwood Crest. This past October the restaurant’s owner wanted to tear it down to expand the hotel he also owned next door. Within two weeks, preservation league volunteers, led by the group’s cofounder, Jack Morey, raised the $20,000 needed to unbolt the structure and store it. Plans call for the Surfside to be reborn as the Crest’s new beachfront visitors’ center.

In spite of the league’s efforts, in the past two years more than two dozen old motels in the three towns have come down. Among the fallen are the Frontier Motel, with its wagon-wheel light fixtures and framed plastic six-guns, and the renovated Memory Motel, which, despite a new water slide and rock ’n’ roll murals, was flattened in 2001 to make way for a six-story condo. “If you have an old 18-unit motel you think is worth $600,000 and someone offers you a million for it, you’re going to say, ‘Good-bye! Here’s the key,’ ” says Mike Preston, the Wildwoods’ construction official and the zoning officer for Wildwood Crest.

“The Wildwoods are probably the last and the cheapest resort spaces available on the JerseyShore,” says Wildwood planning-board member Pete Holcombe, 57. If a new building boom starts here, even National Register status won’t stop the demolition. “Although we can’t prevent people from tearing down Doo Wop buildings,” says Holcombe, “we can convince them they have a valuable asset.”

Indeed, a number of old motels—such as the Pink Champagne—are undergoing face-lifts. “We restored the neon sign using the original blueprint,” says owner Andrew Calamaro, 60. “The locals use it as a landmark.” Calamaro takes his responsibilities to heart. When he replaced the wooden champagne glasses on guest room doors with newer versions (he wanted the champagne sloshing rakishly to one side), he saved the originals. “For me, it’s just a gut reaction to keep the old,” he says. Calamaro is obviously in sync with his guests; many are customers who ask for the same room year after year. Referring to a group that just checked out, he says, “This was their 33rd year.”

But the motels can’t depend solely on their old customers. “One of the problems with the Wildwoods is that the parents of the families who have been coming back to the same motel for years will be dying off,” says architect Richard Stokes, “and their kids are going to places like Florida instead.” Stokes advises owners to lure a new, younger generation of guests not only by dusting off authentic ’50s features, but adding shiny new ones such as lounges and flat-screen TVs. Preservation league member Elan Zingman-Leith, 51, who’s done preservation work in Miami’s resurrected South Beach, agrees that the Wildwoods needs to turn up the volume. “If Wildwood is going to succeed, it has to be a keyedup, brighter-than-it-really-was-in-1960 version.”

Helping push it that way, the Penn/Yale/Kent State students brainstormed ideas aimed at revitalizing the Wildwoods by pulling in younger tourists who don’t remember the ’50s while holding on to the regulars. Their 1999 report called for embellishments such as bigger, louder signs and more of them. George Thomas, who taught some of their workshops, says approvingly, “It’s historic preservation but on steroids.”

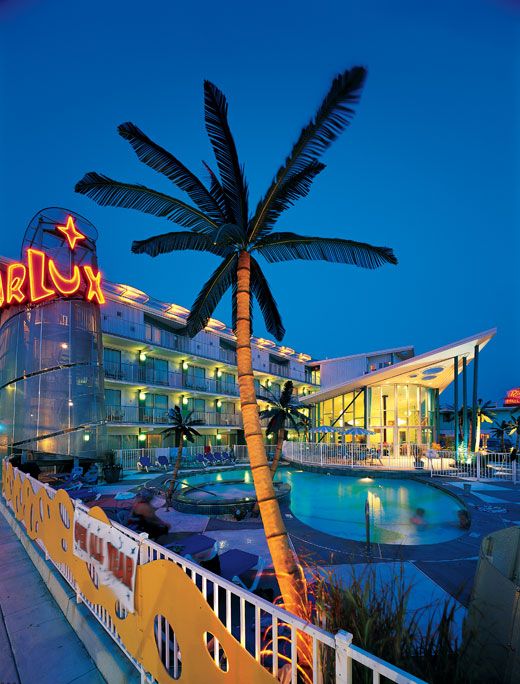

A notable effort to balance new cool and old cool is the Starlux, a debonair addition to Wildwood’s Rio Grande Avenue. The Starlux was a nondescript late-’50s motel until 1999 when amusement-pier mogul Jack Morey bought the building and, for $3.5 million, made it a Doo Wop revival demonstration project. “The Starlux was conceived as a year round motel,” says Stokes, who designed it. He expanded the motel and spruced it up with sling chairs and lava lamps. But he also added a new pool, conference facilities and a dramatic Astro Lounge. He got the idea for the lounge’s jaunty flying- Vroof from an old Phillips 66 station. The overall effect is playful. “We didn’t want the Starlux to look like an authentic ’50s motel,” Stokes says. “What we wanted was a 21st-century interpretation of the ’50s.”

Other businesses have begun climbing aboard the Doo Wop bandwagon. In an ice-cream parlor called Cool Scoops, you can sip a malted while sitting in the rear half of a 1957 Ford Fairlane. A new Harley-Davidson motorcycle dealership resembles a ’50s movie theater, marquee and all. Sporting a more refined retro look is the MaureenRestaurant and Martini Bar, an upscale place with a 27-foot neon martiniglass sign. Even the area’s fast-food chains are ditching their generic signs. Says former Wildwood mayor Duane Sloan: “We tell them, ‘Look, we want angles, glass, neon. We want it to look unlike what you would see anywhere else.’ ” Sloan, 37, believes the Wildwoods’ unique style will survive. “Doo Wop isn’t something you can define exactly,” he says. “It’s more of a feeling. Really, what we want to be is cool.”