Doris Duke’s Islamic Art Retreat

The Honolulu hideaway built by “the richest girl in the world” is now a museum showcasing her unique collection of Islamic art

In 1938, American tobacco heiress Doris Duke embarked on one of her periodic shopping trips to Europe and Asia. Then 25, “the richest girl in the world”—as newspapers had dubbed her when she was a child—was eagerly acquiring antiques and fragments of old buildings to outfit her lavish new home in Hawaii, which she called Shangri La. “It seems almost incredible,” wrote New York Daily News society editor Nancy Randolph, “that there can be a square inch of space left . . . for another bit of bric-a-brac, after the months and months Doris has spent scouring Europe and the Far East for furnishings and knickknacks.”

Today those “knickknacks” form the nucleus of one of the most spectacular collections of Islamic art in America. Duke, who died in 1993 at age 80, spent nearly 60 years filling her secluded Hawaiian home with more than 3,500 art objects, almost all from the Muslim world: ceramics, textiles, carved wood and stone architectural details, metalwork and paintings. The oldest pieces date from the 7th century, but the majority come from the 17th to 19th centuries.

Having no direct heirs, Duke left the bulk of her billiondollar estate to charity. Among other bequests, her will established the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art to “promote the study and understanding of Middle Eastern art and culture.” The foundation transformed her Hawaiian hideaway into a museum, which opened in November 2002. Tours have been sold out ever since, hardly surprising in light of Americans’ newfound hunger to understand the Islamic world. An additional lure is the chance to step inside the dream house of one of the wealthiest, most eccentric and most reclusive public figures of the 20th century.

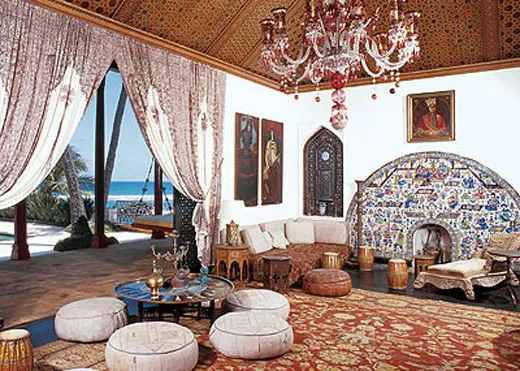

“For most Islamic art historians, Shangri La was a kind of rumor, a shadowy place everyone had heard about but few people had actually seen,” says Thomas Lentz, director of the Harvard University Art Museums, who visited the new museum last year. “Walking into that building for the first time was an amazing experience. It’s a kind of marvelous jumble of mediums, periods and quality you wouldn’t find anywhere else. To see an imitation of a 17th-century Safavid palace facing a huge swimming pool on a spectacular site on the coast of Hawaii—after a while, the mind starts to whirl.” Shangri La’s five acres are tucked into an upscale Honolulu neighborhood near the promontory Diamond Head on Oahu. Access is limited to a dozen visitors at a time, who arrive by van four to six times a day from the Honolulu Academy of Arts, about six miles away, where a new Duke Foundation-funded gallery of Islamic art serves as an introduction to the museum.

Duke, born November 22, 1912, was the only child of Nanaline Lee Holt Inman Duke, a chilly, distant figure, and James Buchanan Duke, the hot-tempered, high-living founder of the American Tobacco Company (original maker of Lucky Strike cigarettes) and the Duke Power Company, as well as the benefactor and namesake of DukeUniversity. The press welcomed Doris as “the Million Dollar Baby” and claimed that she ate from a 14-carat-gold dish. Her father lavished the little girl with gifts (a pony, a harp, furs) and named his private railway car Doris.

At his death in 1925, “Buck” Duke left 12-year-old Doris a $50 million fortune. (His widow had to make do with a $100,000 annual allowance.) Doris asserted her independence early on. At 14, she took her mother to court to stop the sale of Duke Farms, the family’s baronial estate in New Jersey— and won. When she received the first chunk of her inheritance on her 21st birthday (along with an accordion, which she’d requested from her mother), photographers laid siege to the family’s 54-room Fifth Avenue mansion. Newsweek was already calling her a “legendary figure.”

As a young woman, Duke was unpretentious, headstrong, adventurous and reserved, even reclusive. The ferocious press attention she endured from childhood fed a lifelong mania for privacy. She refused virtually all interviews and booked hotel rooms under assumed names. Slender and leggy with exotically large eyes and a prominent chin, she was self-conscious about her height (6 foot 1)—in photographs with shorter companions, she often slouched or leaned. She inevitably made good copy. She converted a B-25 bomber into her own private luxury airliner and for years kept a pair of Mongolian camels at one of her estates. When local officials forbade camel ranching, she gave the animals the run of the mansion’s ground floor, carpets be damned.

“She had a very soft voice,” says Emma Veary, 73, a longtime friend who was often a guest at Duke’s homes. (Besides Shangri La and Duke Farms, there were estates in Rhode Island, New York and California.) “We called her ‘Lahi Lahi,’ which means fragile in Hawaiian, because of her voice.” But she wasn’t mousy, Veary says. “In her quiet way, Doris was very strong. She knew what she wanted, and she had the wherewithal to get it.”

In 1935, at 22, Duke married James H.R. Cromwell, a 38- year-old sportsman and gambler who was going through his own inheritance at a furious clip. The couple set sail on a tenmonth, much-publicized round-the-world honeymoon, with stops in Europe, Egypt, India, Indonesia and China and meetings with both Stalin and Gandhi.

For Duke, the honeymoon was a life-changing experience— no thanks to Cromwell, to whom she quickly cooled (starting when his check for the first leg of the honeymoon bounced). She developed a passion for Islamic art, especially the graceful royal architecture of Mogul India. She was especially moved by the Taj Mahal, the Muslim mausoleum completed in 1647 in Agra, India, by the emperor Shah Jahan. Inspired by motifs she saw there, Duke immediately ordered a sumptuous marble bedroom-bathroom suite, inlaid with jade, malachite and lapis lazuli. The couple intended it for a wing they planned to add to El Mirasol, the Palm Beach estate of the groom’s mother, Eva Stotesbury. (Critics referred to the proposed addition as the Garaj Mahal.)

Duke also fell hard for the last stop on the honeymooners’ itinerary: Hawaii. Delighted by the island chain’s climate, informality and remoteness, the couple extended their stay to four months. By the time they left, the young bride had dropped the idea of moving in with her mother-in-law and had resolved to create an Islamic-flavored home of her own on Oahu. In a rare public comment, she explained her thinking in a 1947 article for Town & Country: “The idea of building a Near Eastern house in Honolulu must seem fantastic to many,” she wrote. “But precisely at the time I fell in love with Hawaii and decided I could never live anywhere else, a Mogul-inspired bedroom and bathroom, planned for another house, was being completed for me in India, so there was nothing to do but have it shipped to Hawaii and build a house around it.”

Socialites were expected to furnish their mansions with art, of course, though not usually with Islamic art. “Doris Duke was perfectly comfortable living with old masters and American decorative arts and furnishings, which she grew up with and had in her other homes,” says Shangri La’s executive director, Deborah Pope. “But when she built her own house here in Hawaii—and this was all her—it was a declaration of her own aesthetic. She had no need to do things because other people were doing them.”

The house was basically completed in 1938, the first private home in Hawaii to cost more than a million dollars ($1.4 million to be precise). Duke, a lifelong movie buff, took its name from the 1937 film of the book Lost Horizon, about a remote and secret paradise called Shangri-La, where no one ever grew old. After separating from Cromwell in 1940, Duke wintered nearly every year at her tropical estate. (Her only child, a premature daughter, died 24 hours after birth in 1940. Asecond marriage, to Dominican playboy Porfirio Rubirosa in 1947, lasted just a year.)

Shangri La’s New York- and Palm Beach-based architect, Marion Sims Wyeth, had first proposed a huge and imposing mansion, but his young client overruled him. The completed 14,000-square-foot house is hardly small, but it is low and rambling rather than grand. It reveals its secrets step by step. Facing a banyan-shaded front courtyard at the end of a twisting, gated driveway, the house’s exterior is unremarkable: a plain one-story plaster wall bisected by a dark wooden door. Behind the door, elegantly appointed living spaces and walkways radiate asymmetrically from an inner courtyard, much as they do in homes of the wealthy in the Middle East.

But “you wouldn’t find this home in the Islamic world,” says Sharon Littlefield, Shangri La’s curator, “partly because it is such a mishmash of different cultures and regions. It’s definitely one collector’s personal vision.” In Town & Country, Duke called the décor “Spanish-Moorish-Persian-Indian.” She chose the placement of every tile, dish and lamp.

The interior is especially rich in ceramics. Duke was fond of mina’i ware (from the Persian word for “enamel”), delicate glazed pottery from 12th- and 13th-century Iran that is commonly painted in gold, turquoise and cobalt blue before being fired a second time. Some moon-faced horsemen adorning the ceramics have a decidedly Chinese cast, a legacy of Buddhist art that early travelers imported into Iran. “We may think of the Islamic world as isolated from other cultures,” says Littlefield, “but there was a huge amount of trade going back and forth with China and later Europe.”

The prize of the collection is a large, exquisitely crafted mihrab, or prayer niche. The fixture, which came from a wellknown tomb in Veramin, Iran, and dates to 1265, once oriented the devout toward Mecca. Its surface is composed of luster tiles, a luxurious, hard-to-work medium that, according to Persian chronicler Abu’l Qasim in 1301, “reflects like red gold and shines like the light of the sun.” Duke’s mihrab is significant not only for its monumental size and superb craftsmanship but also because it’s signed and dated by a member of the Abu Tahir family, an illustrious line of Kashan potters who passed down their glazing secrets from father to son and dominated the industry for four generations.

“This is one of the most important works of Iranian art and possibly of Islamic art in North America,” says Marianna Shreve Simpson, a former curator of Islamic Near Eastern art at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and a consultant to Shangri La from 1997 to 2003. “Few such virtually intact interior features survive today—certainly nothing of this grandeur.” Duke bought the mihrab from a dealer in 1940 and installed it off of Shangri La’s living room, pointing not to Mecca but to Mexico. Though Duke was not religious, she meditated daily and told friends she believed in reincarnation. “She was interested in everything,” says Violet Mimaki, 69, her Shangri La secretary and estate manager for 22 years. “I can’t say that she was a Catholic or a Buddhist, but she had a Bible in her bedroom. And copies of the Koran—lots of them.”

The oldest Koranic text in the collection is a sheet of parchment from around a.d. 900. The bold, angular lettering in ink and watercolor is an early writing style called Kufic script. Considered the literal word of God, the Koran has always been viewed as Islamic art’s most exalted subject, and Shangri La is everywhere embellished with Koranic calligraphy and geometric abstractions. Awall of the inner courtyard, for example, is embedded with a rare collection of monochromatic tiles believed to have once graced the Takht-i Sulayman, a 13th-century Mongol palace in Iran. As in much of the Muslim world, the home’s decorations—from tiles and wall hangings to carved doors and ornamental ceilings—enliven spaces the way prints or paintings animate a Western home. In fact, there’s a notable absence of pictures or other personal effects on display at Shangri La. “This is how it was in Doris Duke’s lifetime,” says Littlefield. “I think there were a few photos in her bedroom, mostly of her dogs.”

Though Duke mixed centuries and continents at will, her focus on light, color, texture and geometric repetition helps to unify the result. “She was interested in surfaces,” says Kazi Ashraf, an assistant professor of architecture at the University of Hawaii, who acted as a consultant to the new museum. “That’s why she was drawn to marble, which changes with the light.” It was the look and feel of the Taj Mahal’s stonework, he points out, not its overall form, that first inspired her to build an Islamic-style home.

Duke used traditional elements in untraditional ways. “In my Indian bedroom,” she wrote in 1947, “the carved, cut-out marble jalis, or screens, which were formerly used by Indian princes to keep their wives from other eyes, have a new purpose: they are not only decorations, but a means of security, for they can be locked without shutting off the air. . . . ”

In a more modern vein, an entire wall of Shangri La’s living room is a sheet of glass that can be made to disappear into the basement. “It’s one of the marvels of the 1930s,” says Jin DeSilva, caretaker of the house during the last 14 years of Duke’s life. When the wall vanishes, the room opens directly onto Diamond Head. “When Miss Duke was alive,” says DeSilva, “she rarely lowered the glass wall completely. At one time she had 12 German shepherds, and if this was down they’d come running inside wagging their tails. We had two or three accidents that way.” An enormous ceramic vase was one such casualty, as its cracks attest. “Miss Duke would sit down and glue everything together herself,” DeSilva says.

Several of the artifacts in the room once belonged to publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst. Facing bankruptcy in the late 1930s, Hearst was forced to sell many of his antiquities at bargain prices. Duke took advantage of the tycoon’s distress by picking up, among other objects, a medieval stone fireplace from Islamic Spain, which is now installed in the living room.

Duke loved bargains. Gossip columnist Elsa Maxwell once wrote of Duke and her first husband that “he could, and did, spend a fortune; she thinks twice before agreeing to buy a ticket to a charity ball.” Following a rare photographic session for Life magazine in 1939, Duke asked photographer Martin Munkacsi where she might buy a camera wholesale. Areceipt for three antique bureaus she purchased in Damascus, Syria, in 1939 bears the dealer’s notation: “Only: Fourty- Three Dollars & 60/100.” The merchant obviously understood his customer.

Duke was no purist.To dress up a courtyard wall, she custom- ordered reproduction tile mosaics from a workshop in Esfahán, Iran. And she had a studio in Morocco fabricate the ornately carved and painted wooden ceilings of her foyer and living room. Her taste was defiantly personal. To guard her front door, she selected a pair of stone camels from a Honolulu department store.

But if Shangri La’s décor was eclectic, it was hardly thrown together. In 1938, Duke visited Iran with art adviser Mary Crane, a New YorkUniversity graduate student. There they obsessively sketched and photographed a 17th-century royal pavilion in Esfahán known as the Chihil Sutun. Duke had a scaled-down version built at Shangri La, which she called the Playhouse and used as a combination guest and pool house.

Unlike most of the art in Shangri La, the works inside the Playhouse teem with human figures. While Sunni Muslims have long mistrusted representational art—even pictures of animals and buildings—as invitations to idolatry, Shiite Muslims tend to be more easygoing about representation, especially regarding their secular art. A large tiled fireplace surround in the Playhouse, depicting court life during Iran’s Qajar dynasty early in the 19th century, is decorated with colorful acrobats and musicians. Nearby, a Qajar oil painting shows a young, bejeweled woman (p. 79) strumming a longnecked stringed instrument. “One reason Iran produced so much figural art is that it had a rich tradition of secular liter ature,” says Littlefield. (Persians devoured love poetry in particular.) Until recently, scholars dismissed Qajar art, with its European influences, as decadent; Duke found it “amusing” and thus perfect for the Playhouse.

“Doris was a prankster,” says friend Emma Veary, whose Hawaiian mother Duke often enlisted as a traveling companion. “Mother was very dark-skinned, and once, for a party, Doris dressed her in saris, put her on pillows, and stuck diamonds on her nose, then introduced her to everyone as the maharani of somewhere. People bowed and kowtowed to her all night. Doris had told her, ‘Don’t say anything,’ so Mother just glared at the people.”

In her first years in Hawaii, Duke sometimes entertained socially but, says museum director Deborah Pope, “usually with just a small circle of friends, mostly native Hawaiians. A lot of them were swimmers, surfers, dancers and musicians— people with day jobs. They weren’t socialites. That’s what she came to Hawaii to get away from.” Shangri La was not air-conditioned, and Duke padded around it in bare feet or flip-flops. She learned to play Hawaiian music, hula and surf (the collection includes some old surfboards), and she once won an outrigger canoe race off Waikiki Beach with her friend Sam Kahanamoku, brother of legendary surfer and Olympic gold medal swimming champion Duke Kahanamoku.

In an interview with Andy Warhol in 1979, writer Truman Capote recalled being surrounded by a pack of Duke’s snarling dogs while taking a stroll around Shangri La one evening. “No one had warned me,” Capote said, “that each night after Miss Duke and her guests had retired this crowd of homicidal canines was let loose to deter, and possibly punish, unwelcome intruders.” After standing rigid for what seemed to him like hours, Capote was finally rescued when a gardener whistled to the dogs and they trotted off, tails a-wagging.

Now that the dogs are gone, visitors to Shangri La can experience Duke’s garden as a paradise of shade trees, running water and quietude—a recurring image in the Koran. Aparticular gem is the Mogul garden, a smaller version of the ShalimarGardens in Lahore, Pakistan, that reveals itself like a mirage behind a door near the entrance. Its centerpiece is a narrow pool of water punctuated by lotus-shaped fountains.

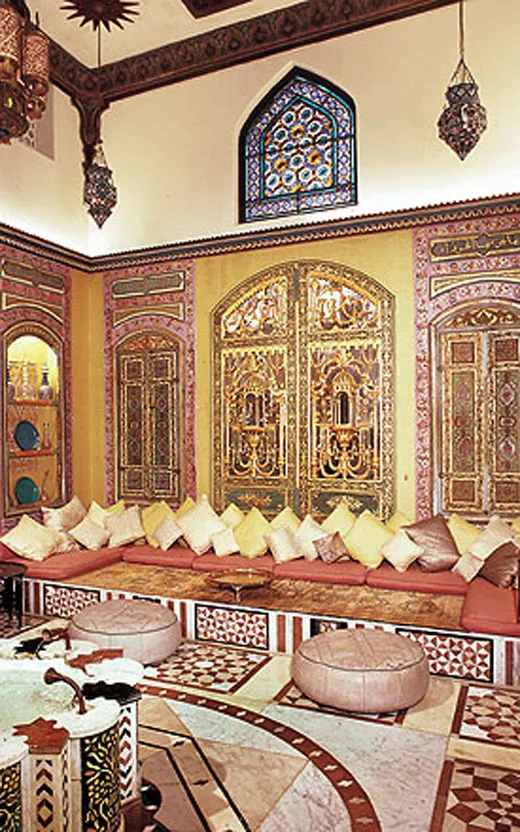

The formality of the Mogul garden reflects Duke’s later taste. Her last major acquisition was an elaborate interior from a deteriorating 19th-century mansion in Damascus, which she bought from the estate of New York dealer and philanthropist Hagop Kevorkian in the early 1980s. The home was one of at least four villas owned by the Quwwatlis, a wealthy merchant family in the old city. “When the crates [containing the dismantled room] arrived, the boards were all black and dirty,” says ex-secretary Violet Mimaki. Duke, then in her 70s, oversaw a months-long clean-up campaign. “She had us spread everything out in the courtyard, and she tested out different cleaning solvents with Q-Tips,” Mimaki recalls.

Duke supplemented the room’s original interior with glassware and metalwork she already owned and cabinetry she commissioned from woodworkers in Rhode Island. She called it the Turkish Room. Below a few small, high windows, everything seems to be carved, cushioned, mirrored, inlaid or gilded. The overall effect is a bit overwhelming. “It’s clearly not a space you live in,” says Deborah Pope. “Although Duke used it for entertaining, it’s more of a display space. At this point, she was thinking about how she wanted the house to be when she was no longer here.”

Despite its Hollywood name and its owner’s many eccentricities, Shangri La is the creation of a serious collector, not a dilettante’s indulgence. “There was a degree of escapism maybe in that Doris Duke was trying to distance herself from her upbringing,” says Sharon Littlefield, “but this was no passing fancy. Her interest in Islamic art was very personal to her, and it sustained her to the end of her life.”