Drawn From Life

Artist Janice Lowry’s illustrated diaries record her history—and ours

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Janice-Lawry-diary-631.jpg)

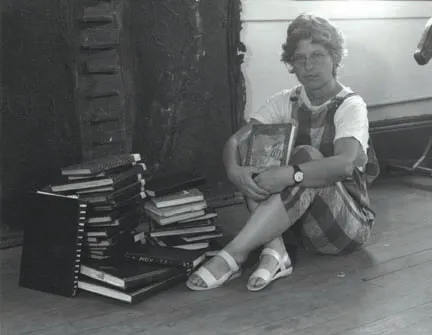

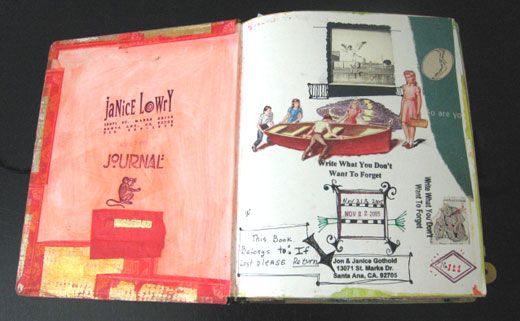

When Janice Lowry turned 11, inspired by reading The Diary of Anne Frank, she began keeping a journal. Not unusual for a young girl. What's unusual is that throughout her life, Lowry—who died of liver cancer this past September at age 63—kept up her diaries.

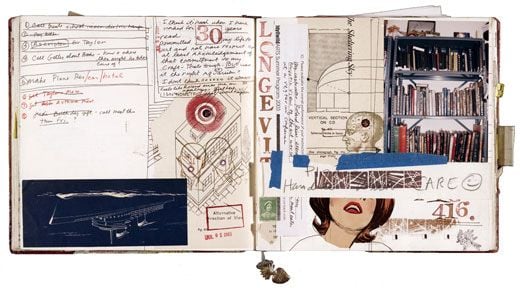

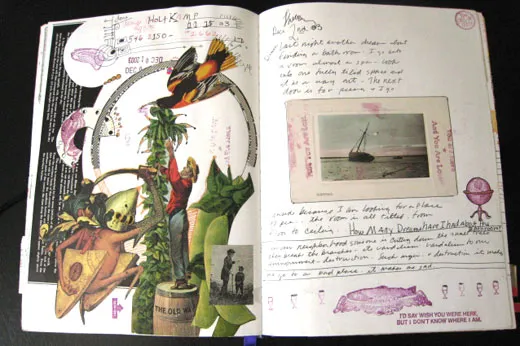

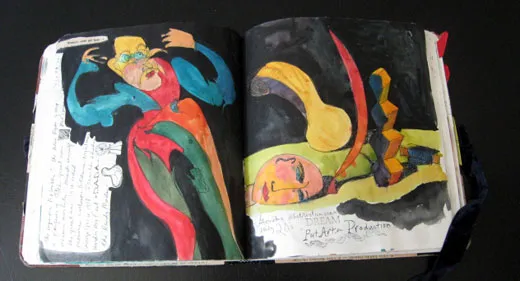

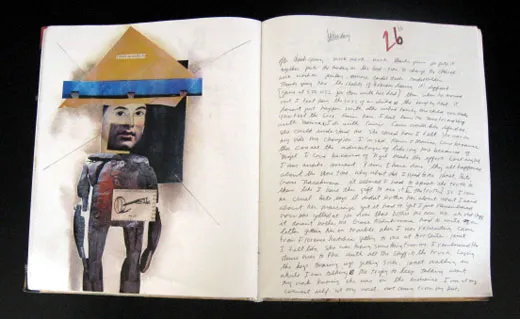

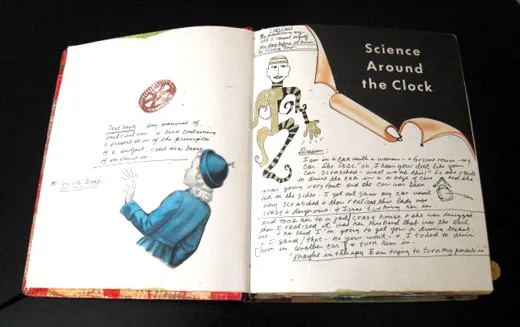

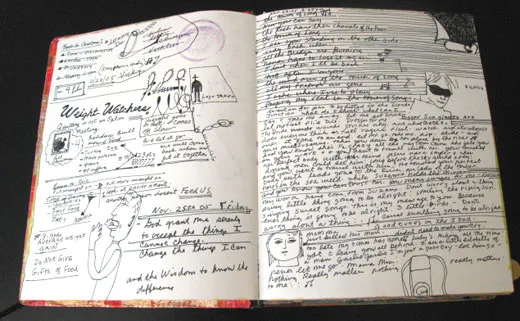

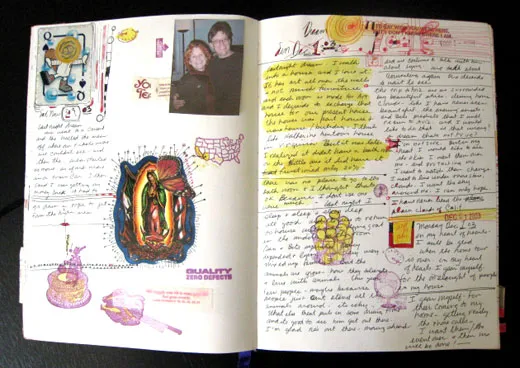

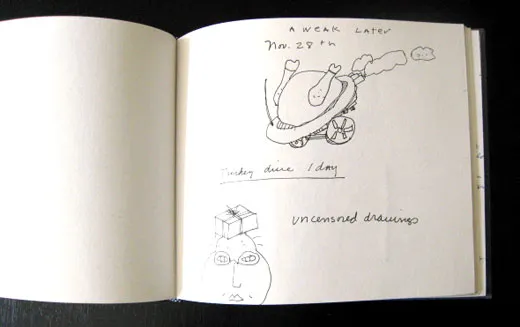

From childhood on, Lowry filled small notebooks with daily musings and drawings. Then, in the mid-1970s, she moved to a larger format, 7 1/2- by 9 1/2-inch notebooks. For almost 40 years, Lowry—an artist best known for her intricate, three-foot-tall assemblages—filled the roomier notebooks with jottings and sketches. The pages contain everything from original drawings, collages and rubber-stamp images to observations about herself and the world, including the commonplace "to-do" lists many of us make: "pay bills/make plane res/get asthma med/Judi birthday gift."

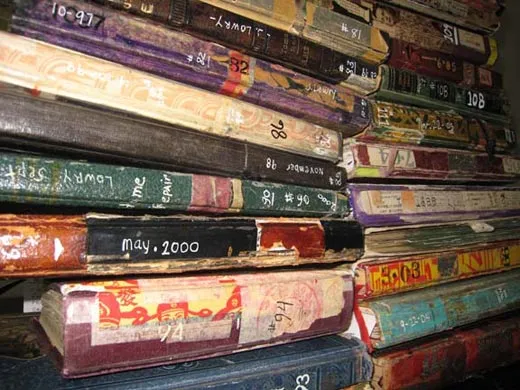

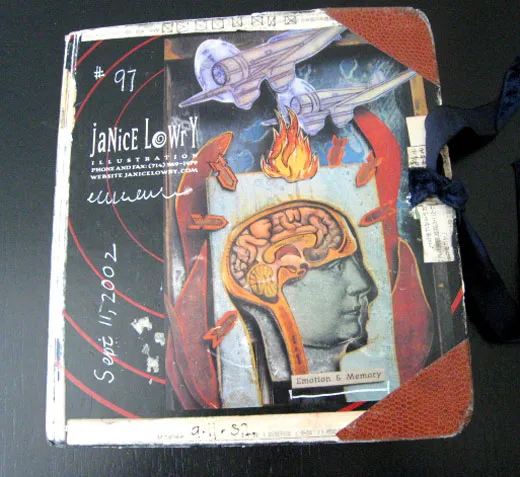

Each notebook spans about four months, transcending minutiae to record the life of our times as well as her own. Entries touch on events from a child's birthday to the contested presidential election of 2000 and the anniversary of the September 11 attacks. This past July, the Smithsonian Archives of American Art acquired all 126 volumes.

Artists' journals can be an art form unto themselves, a taxonomy of days that attempt to capture the random rush of creativity. Free of formal constraints (beyond the size of the page), artists can use anything that comes to mind, eye or hand. "I call these books 'reportage,'" Lowry said in an August interview. "There are certain themes that run through the journals consistently—health, motherhood, political things, being an artist, even fashion and television. Originally, I saw them as books for my sons, so they could see my progress through life. Now they're 126 chapters of a memoir."

Lowry was an art student raising two young sons when she switched to the large-format journals in 1974. "At the time, I didn't have any role models to help me figure out how to do these journals," she recalled. "When I had a vision of something, I could just do it."

In 2006, Patricia House, then director of the Muckenthaler Cultural Center in Fullerton, California, visited Lowry's Santa Ana studio because she intended to include Lowry's assemblages in an upcoming gallery show.

There, House first saw the neatly stacked diaries; she instantly recognized their value and informed Lowry that the collection needed a "steward."

"I've seen a lot of artistic diaries, but these were different," says House. "I saw works of art."

Lowry took her colleague's advice. She put together seven of what she called "packets"—illustrated introductions to the journals—and submitted them to research centers and museums around the country. Liza Kirwin, who is curator of manuscripts at the Archives of American Art, received one of them.

"The packet was very inventive," Kirwin recalls, "with a handmade envelope and very curious contents. It was such a creative expression of an artist's life. About 20 seconds after looking at it, I sent an e-mail message [to Lowry] saying that the Smithsonian should have the journals."

Shortly after, Kirwin says, the artist sent two complete journals to the Archives. "We used them right away for an exhibition of sketchbooks," Kirwin remembers, thereby allowing Lowry to cross off a very important item on one of her last to-do lists: "Find steward for journals."

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)