Drones: The Citrus Industry’s New Beauty Secret

In the future, farmers will use unmanned drones to improve the appearance of their crops

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120309033002AerialwithExp_470.jpg)

Culturally speaking, Americans are anti-wrinkle. We iron them out of our clothes, inject them out of our faces, and retouch them out of our photos. A crease is also a strike against fruit. In the beauty pageant of the citrus packinghouse, oranges are graded on three levels of aesthetic worth: Fancy, Choice and Juice. “In order to be Fancy, the fruit has to be perfectly smooth and can’t have any creasing,” says David Goldhamer, a water management specialist at the University of California, “If it does have creasing, it gets rated as juice fruit, which means it’s worthless to the grower.”

Certain species of Navel and Valencia oranges—the top-selling varieties grown in California—have a wrinkle problem. Scientists theorize this comes from a separation between the peel and the pulp due to the fruit growing too quickly. The rapid expansion of the cells creates small fissures that become noticeable imperfections as the fruit matures. The grower’s potential return drops with every unsightly crop.

Unlike with humans, flawless skin is achieved through stress—specifically, dehydration. When deprived of normal water levels at targeted points in the season, the fruit’s growth slows, allowing the peel and pulp to remain tightly knit. When the water levels come back up toward harvest time, the fruit recovers to a consumer-friendly size—neither too small nor too large—and farmers maximize their profit. The resulting reduction in water use is also a win for a drought-stricken state.

Hydrologists call this Regulated Deficit Irrigation (RDI). Farmers are motivated to put the strategy into practice by the promise of high returns, but implementation in the field is extremely time-consuming, inefficient, and unreliable. Manual monitoring requires driving a truck out into the grove, plucking a leaf from a tree, inserting it into a pressure gauge and applying extreme pressure to the leaf until moisture seeps out. Then doing it again. And again. “There’s simply no time to do enough trees,” says Goldhamer, “There’s so much variability that if you happen to pick a tree that’s very stressed or very unstressed, you get a false impression of what’s going on broadly in the orchard.”

Enter the drone.

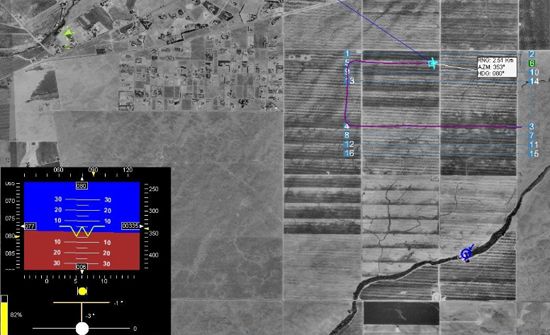

Water management researchers have been experimenting with unmanned drones that can fly over an orchard and record heat levels across vast swathes of land using aerial imagery. Thermal infrared cameras take thousands of images at regular intervals on a voyage across hundreds of acres. Computer software stitches the images together to create a super high-res image, in which each pixel can be read for temperature—cooler areas show up in cool tones, while warmer areas appear orange, red and yellow. In the aerial image here, powerlines, asphalt roads, metal towers cut across the picture in yellow. The scientists were experimenting with different levels of irrigation, which are visible in the patterns of blue and red across the tree canopy.

“You can clearly see those stress levels associated with different amounts of water,” Goldhamer explains, “You can see there’s nothing consistent about the colors and that’s the problem. When you’re irrigating, you’d think the stress levels would be uniform, but it’s not clear at all and that’s the challenge of trying to manage a commercial orchard—all the variability. Some trees get enough water, some don’t. That’s the game in trying to move the science forward, making the irrigation more consistent. Technology that enables monitoring all the trees at once is the current state of the art.”

At this point, the state of the art is not the state of crop management in California. But Goldhamer is quick to assert, “It isn’t a matter of if this technology will be used, it’s a matter of when.” Drone manufacturers, he says, are looking for additional opportunities for their aircraft, and the Obama administration has charged the FAA with drafting guidelines for commercial use of drones in the U.S. In a couple of years, farmers may be able to sit at a computer and monitor the stress level of every single tree in their orchard, ensuring that each orange they send to the packing house has skin perfect enough to be called Fancy.

All photos are courtesy of David Goldhamer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)