The Earliest Memoir by a Black Inmate Reveals the Long Legacy of Mass Incarceration

The story of “Rob Reed” is finally published, 150 years after his release

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/cf/6fcfc789-2d5b-4906-8c22-5219a00e5f4b/janfeb2016_o07_phenom-web-resize.jpg)

In the fall of 2009, an unusual package arrived at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, at Yale University. Inside was a leather-bound journal and two packets of loose-leaf paper, some bearing the stamp of the same Berkshire mill that once produced Herman Melville’s favorite writing stock.

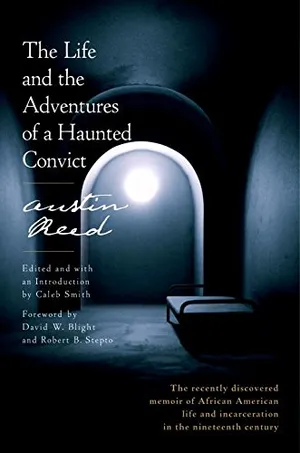

Joined together under the title The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict, the documents told the story of an African-American boy named “Rob Reed,” who grew up in Rochester, New York, and had been convicted, in 1833, while still a child, of arson. Reed spent nearly six years in the House of Refuge, a juvenile home in Manhattan; he was released in 1839, but, accused of theft, he was soon behind bars again, this time at New York’s Auburn State Prison.

Reed never denied his guilt. But he was appalled by the conditions at the House of Refuge and especially at Auburn, an early example of the so-called “silent” detention model, which would become the basis for the modern prison system—inmates labored by day and spent their nights cooped up, often alone, in a small cell. In Reed’s day, the slightest infraction was grounds for a lashing or a trip to the “showering bath” (an early take on waterboarding). “The high and noble mind which God had given to me [was] destroyed by hard usage and a heavy club,” Reed laments. His account ends in 1858, with his discharge from Auburn.

“The big question was what exactly we were looking at,” says Caleb Smith, a literature professor at Yale, and one of three experts asked by the Beinecke to evaluate the manuscript. “Was it a novel? Was it a memoir?”

An expert in prison literature, Smith felt sure that the book was written by someone with firsthand knowledge of 19th-century correctional facilities. And if Haunted Convict was a genuine account, it would be groundbreaking: the earliest-known narrative penned by an African-American prisoner. Moreover, it had been unearthed at a propitious time. Nationwide, criticism of the costly and overcrowded prison system was growing, as was anger at soaring incarceration rates, especially among young black men.

Smith set out to verify the manuscript, which had come to the Beinecke via a rare-book dealer, who had purchased it at an estate sale. In the New York State Archives, Smith found a House of Refuge file for an arsonist named Austin Reed. Enclosed were two letters written in a script he recognized instantly. With the help of Christine McKay, then a genealogist at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Smith combed through 19th-century census documents. Austin Reed, born around 1823, was listed as “mulatto”; his mother was a laundress; his father died when he was young; he had brothers and a sister. It all lined up. Subsequent tests on the age of the paper and ink confirmed the documents’ authenticity.

This month, Random House will publish Haunted Convict, with the text preserved largely as Reed wrote it. Smith, who contributed the book’s foreword, teaches literature to inmates at Connecticut’s Cheshire Correctional Institution, and he shared the manuscript with his students there. They recognized the early roots of “racialized policing and incarceration, which has persisted into the 21st century,” Smith says. “They identified with Reed’s anger, and his desire to speak truth to power—to show the world what was happening behind prison walls.”