Dave Eggers’ Animals Might Be “Ungrateful,” But They Go to a Good Cause

The author discusses a return to art and his forthcoming book Ungrateful Mammals

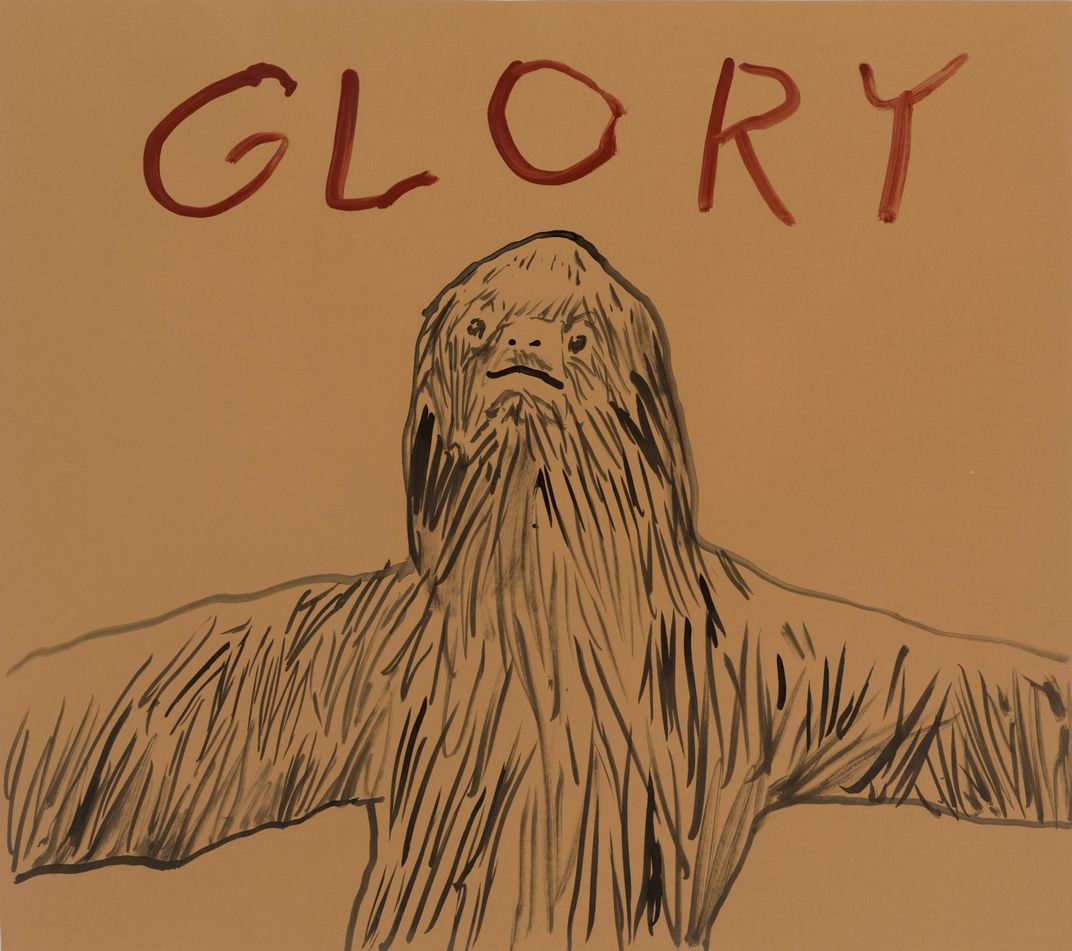

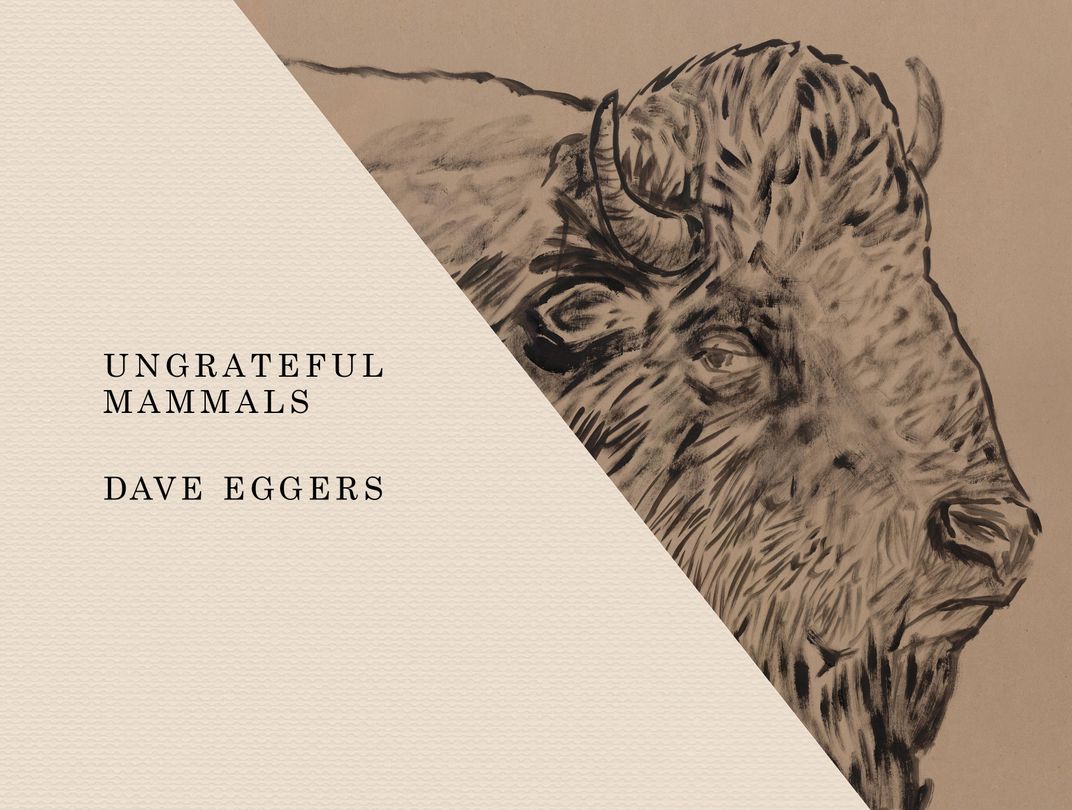

Bestselling author Dave Eggers might just have begun writing as a side project. Before penning acclaimed novels like A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, he was trained as an illustrator. After a 15-year hiatus from art, Eggers has returned to the drawing board with the whimsical new book Ungrateful Mammals. In the book he pairs his sketches with quotations plucked from Bible verses, musings on global politics and the quirky thoughts that run through his head. Proceeds from the book will go to ScholarMatch, a nonprofit that helps underserved students apply to and pay for college.

We caught up with Eggers at 826 Valencia, the headquarters of the coalition of children’s writing centers he founded in San Francisco, to discuss art, social media and these ungrateful mammals.

Ungrateful Mammals

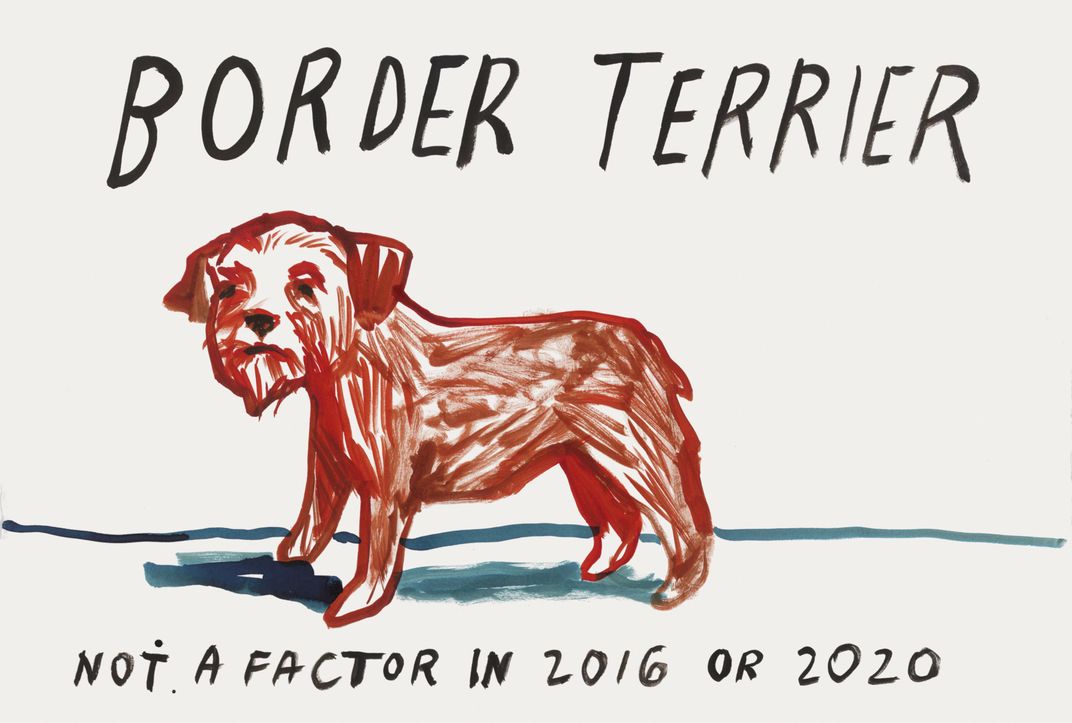

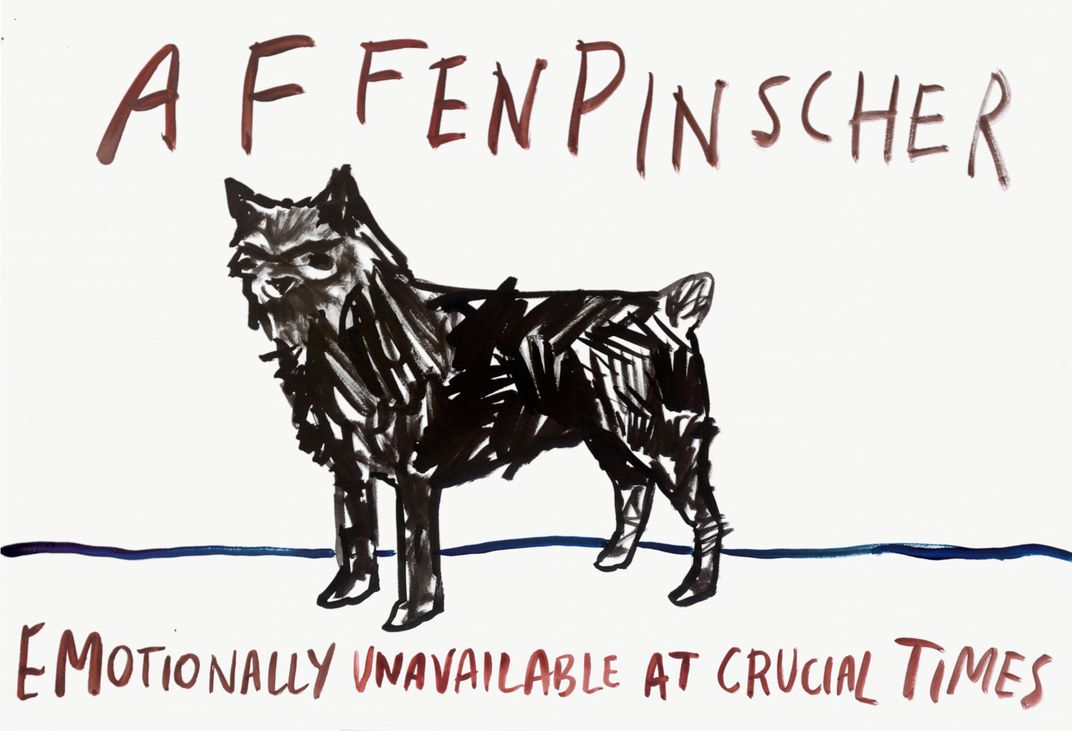

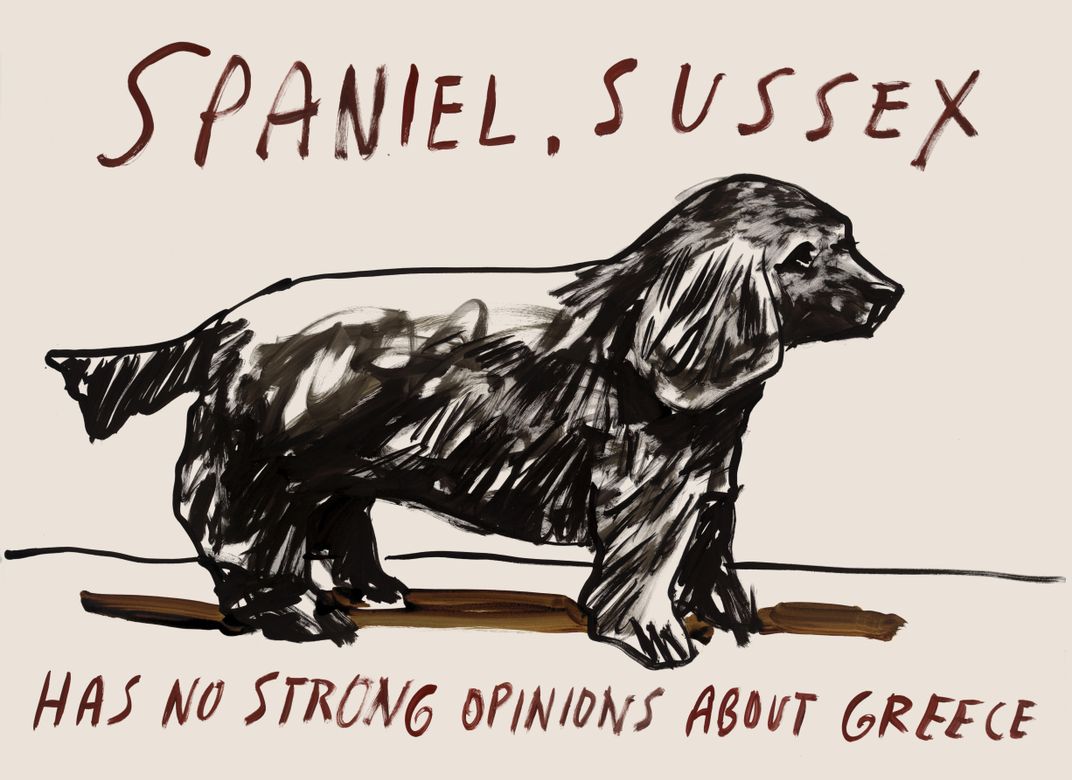

Usually involving the pairing of an animal with humorous or biblical text, the results are wry, oddly anthropomorphic tableaus that create a very entertaining and eccentric body of work from one of today’s leading culture makers.

You haven’t published anything autobiographical since A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius—yet many of the animals in your new book have an almost humanlike self-awareness, coupled with quotes that seem personal. It’s almost as though they’re in on the joke. Where did you seek inspiration in choosing animals, finding text, and pairing the two?

The process for these drawings and paintings is not organized or rational. Late at night, I sit on the floor and I draw animals. After I draw them, the personality of the animal will assert itself and a phrase will occur to me. For some reason, the phrases are often either Biblical or refer obliquely to global political financial crises. Sometimes I just write something that makes me laugh. In all cases, the whole project is absurd, given I’m a grown man.

A number of the quotes deal with the Greek financial crisis. Why the focus on that?

Well, mammals are inordinately interested in the plight of Greek purchasing power vis a vis the European Union. So I’m just reflecting that.

Why did you stop producing visual art for so long? And what made you come back?

I studied painting and drawing most of my life, all the way through college — most of that time in classical drawing programs. But I didn’t really find my voice in the visual arts until about eight years ago, when a gallerist, Noah Lang, thought my drawings might make for a show. We decided to direct all proceeds to ScholarMatch, and that provided the motivation to create these pictures, which otherwise would be too ridiculous to contemplate.

Which artists do you admire?

When I was in art school, artists like Eric Fischl were making it possible to think about figurative art again as a viable pursuit, So he was very important to me. Going further back, I grew up loving Manet, Baselitz, Keifer, Calliebotte, Max Beckmann—usually figurative painters with some narrative quality to their work. Recently, Neo Rausch and Kerry James Marshall are the painters who I find most intriguing.

Which print in Ungrateful Mammals is your favorite?

I still laugh when I see some of the dog drawings. I love dogs, but their overall affect is just goofy. You can’t take them seriously.

You’ve written fiction about how technology can dangerously encroach on our lives. What is your relationship with technology in real life—Twitter, Facebook, podcasts and media in general?

I send email, get email, read the news online sometimes, but otherwise I can’t quite keep up with the volume of stuff available. It’s hard enough getting through the books I want to read. And then there are drawings of sentient animals to make. That takes most of the time I otherwise would spend on social media.

Which books would you recommend to someone looking for a good read?

There’s a great book by Cathy O’Neil called Weapons of Math Destruction. It’s about the ways that the datafication of our lives can be dehumanizing and can infringe on human and civil rights. I recommend it to everyone I know.

Are there any up-and-coming artists or writers that you think people should keep an eye on?

Wajahat Ali is one of the more exciting writers I know. His take on Muslim-American life is crucial and brings needed levity to the discussion.

You and Mimi Lok won an American Ingenuity Award in 2013 for your work with Voice of Witness. What is VOW working on now?

Voice of Witness was so grateful to be recognized with that award, so thank you again. We just published two books in rapid succession. One, called Chasing the Harvest, was edited by Gabriel Thompson and features the stories of migrant workers in the U.S. Peter Orner and Evan Lyon just published Lavil, about life in Haiti after the earthquake in 2011. Both are extraordinarily gripping books, and I continue to believe that oral history is one of the most urgent and immediate ways to learn about otherwise opaque or complex sociopolitical subjects. Plain and simple, you have to listen to the people affected directly.

Because you’ve returned to visual art after a long break, do you think the mission of 826 Valencia will adapt or expand in the future as well?

826 National continues to grow, but the focus will always be on the written word—on making sure young people have a voice and gain power in societal through their ability to express themselves effectively. To that end, a new 826 location will open in New Orleans soon, and there are centers based on our model all over the world. I just visited one in Stockholm a few weeks ago; that was surreal, to see everything looking just like one of our U.S. centers, but in Sweden. Our hope is that the network continues to expand, with communities around the world adapting 826’s ideas to best serve the kids and schools locally.

Writers and artists have always had an important role in society as mirrors or seers. What does that mean in today’s world of mass media and political division?

I think you do what you can, when you can. It’s not more complicated than that.

What are you working on now, or what can we expect from you next?

Around the same time as Ungrateful Mammals comes out, Chronicle Books is releasing a picture book I wrote called Her Right Foot, illustrated by Shawn Harris. It’s about the Statue of Liberty, and with it I’m trying to remind readers what the Statue stands for, and I hope to remind kids who are immigrants, or whose parents are immigrants, that they are welcome, that they’ve always been the lifeblood of the nation.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/71/5b713bc0-9c2a-4b3c-b48d-9a173dcca128/oct2017_a04_prologue-wr.jpg)