Emily Dickinson Was Fiercer Than You Think

A new biopic shows the poet as more than a mysterious recluse

One startling early verse almost didn’t make it into print. “Wild nights—Wild nights!” it cried. “Were I with thee / Wild nights should be / Our luxury!” The poet’s editor dreaded publishing it, he wrote, “lest the malignant read into it more than that virgin recluse ever dreamed of putting there.”

Though Emily Dickinson is one of America’s most important poets, credited with inventing an explosive new type of verse, she’s perhaps best known for the way she lived, withdrawing from daily life in her Massachusetts hometown in the mid-1800s and confining herself to her family home and, often, her room. Historians still can’t agree if she did so for the sake of her health, her art or some other reason. But popular depictions tend to focus more on the closed door than the open mind, so she appears to us a painfully shy cipher or a clinically depressed recluse.

Now a new movie, A Quiet Passion, written and directed by Terence Davies, begs to differ. This Dickinson, played by Cynthia Nixon, best known for her role as uptight Miranda in the HBO series “Sex and the City,” yells, cries and rages—and refuses to go along with her family, her community or her era. And in that regard, she lines up with the fierce, sometimes bitter figure known to today’s scholars. “She felt strongly and rebelled against many received notions of her time,” says Cristanne Miller, a Dickinson expert and chair of the University at Buffalo’s English department.

Church, for instance. Dickinson was intensely interested in both religion and spirituality, but she opted out of church altogether, famously writing that “Some keep the Sabbath going to Church / I keep it, staying at Home.” In the movie, Dickinson exclaims to her father, “I will not be forced to piety!” While Dickinson surely tussled with her family, it’s doubtful she did so in heated shouting matches like those in the film. But Miller, the scholar, acknowledges the challenge of portraying the defiance of a 19th-century poet in an overheated 21st- century medium.

In her poems—she wrote nearly 1,800, most only published after she died—Dickinson compared her life to everything from a funeral to a riddle to “a Loaded Gun,” but the astonishing range of those images isn’t so much a sign of disorder as imagination. “She made choices that enabled her to do the work she wanted to do,” says Miller. “I don’t think she was a tormented soul.”

Related Reads

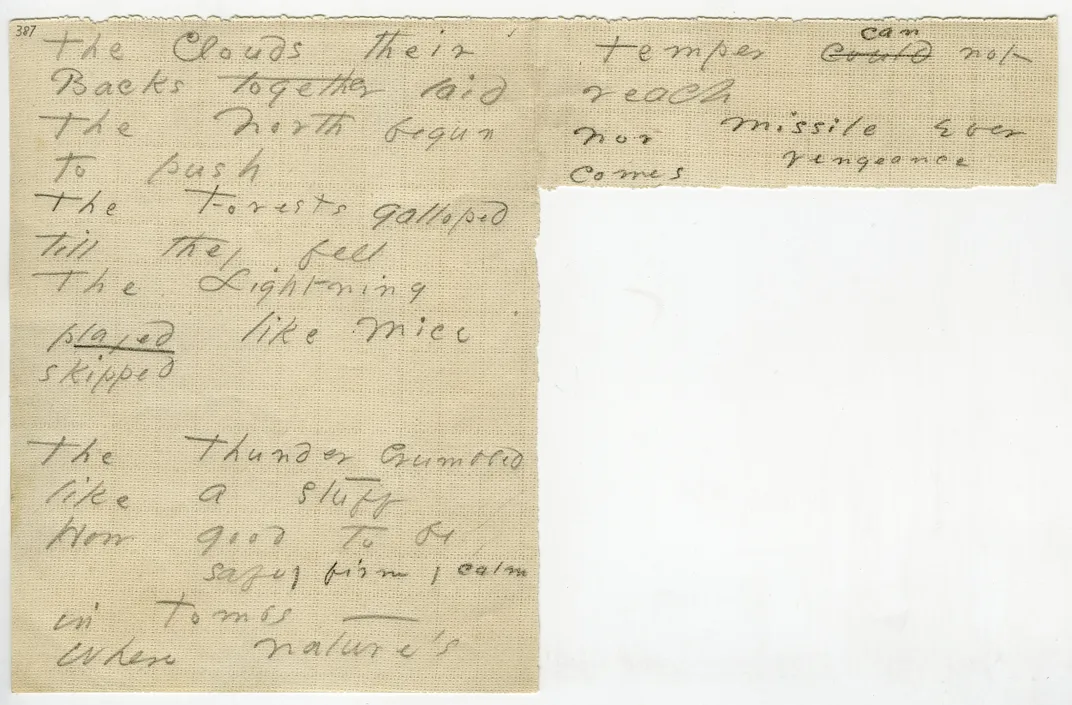

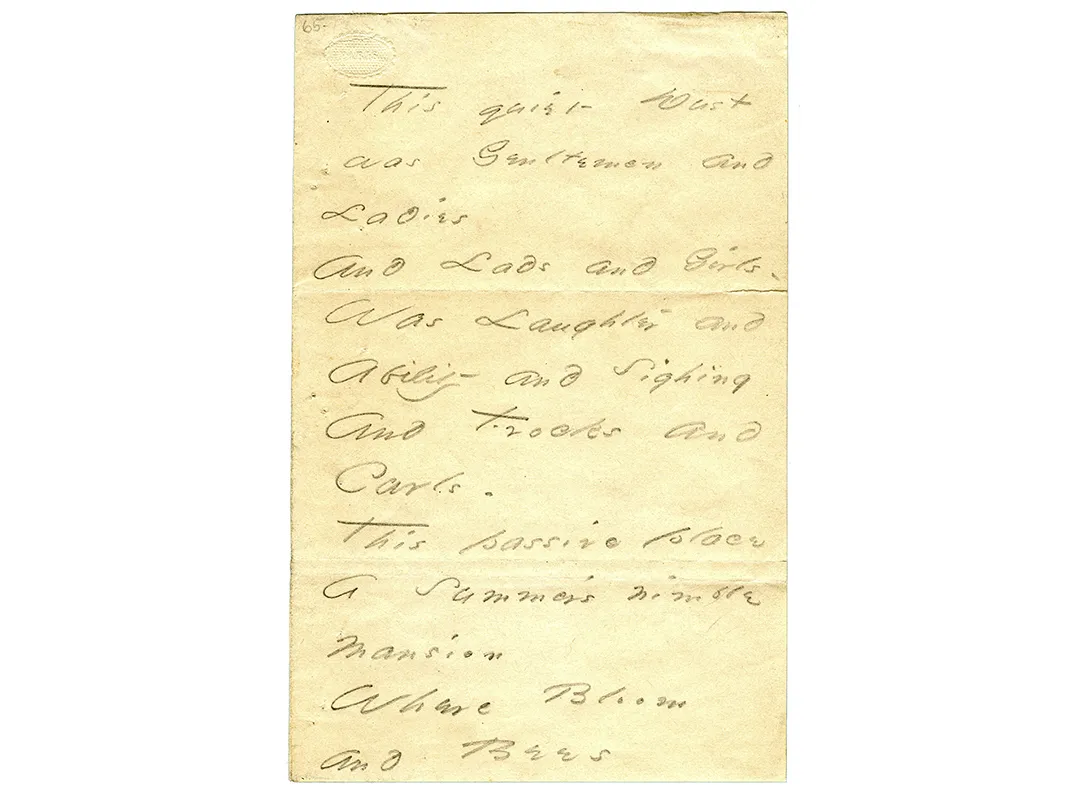

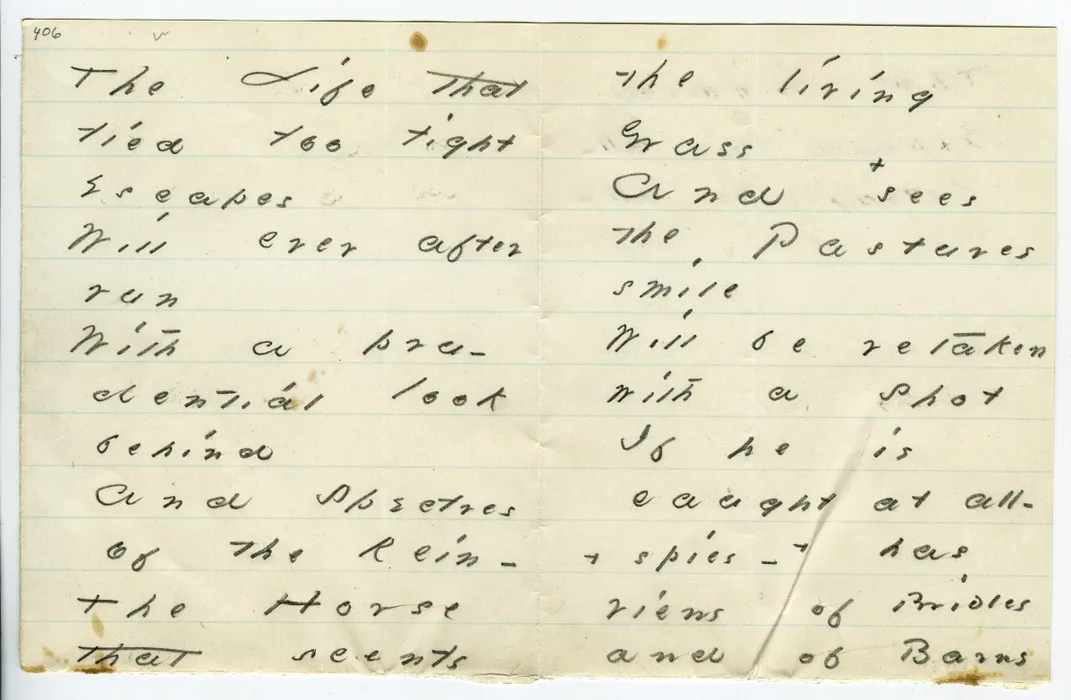

The Gorgeous Nothings: Emily Dickinson's Envelope Poems

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2a/c7/2ac76b82-a73a-4b2f-9646-8a7078ce23c4/apr2017_h01_phenom-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)